APOGS #12: As long as we win

Part Four, Chapter V. Burning the Bodies (1792)

Louise: ‘Will he be safe?’ 'Well, apart from a great earthquake, and the sun going black, and the moon becoming as as blood, and the heavens departing as a scroll when it is rolled together, and the coming of the seven last angels with the seven last plagues – all of which is an ever-present risk, I agree – I can't see much going wrong for him. We'll all be safe, as long as we win.'

last week | main page | reading schedule | cast of characters | further resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings.

This week, we are reading Part Four, Chapter V. Burning the Bodies (1792).

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

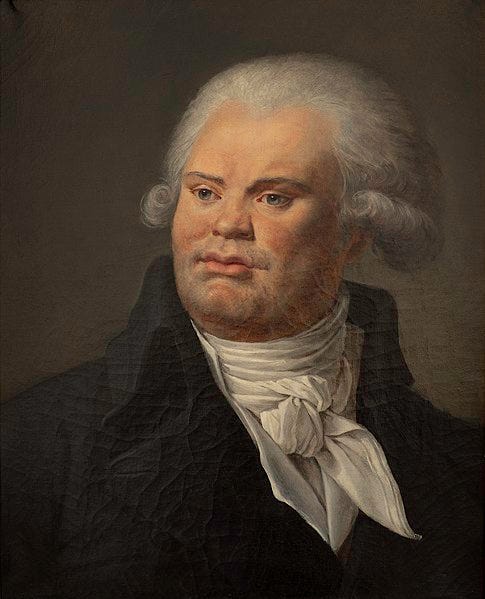

7 August, everything is in place to overthrow the government. Except Danton, who has disappeared. Fabre feels sick, Camille is suicidal, and Lucile’s got her feet up, reading a novel.

9 August, nine a.m. Danton is back from Arcis. He’s put his affairs in order and is ready for revolution. At two p.m., he’s in conference with Marat, who reminds Danton not to trust Roland and Brissot. At four p.m., the royalist pamphleteer Louis Suleau says goodbye to his school friend Camille. Suleau is off to defend Louis to the death.

Danton’s mother-in-law and son leave for a place of greater safety. Gabrielle stays behind with Lucile and Louise Robert. At the Tuileries, King Louis goes to bed alone. He doesn’t get much rest. The Mayor of Paris and Mandat of the National Guard consider the palace’s inadequate defences. “How improvident,” says Pétion.

At midnight, it begins. Danton says “the patriots” have taken over City Hall and set up an Insurrectionary Commune. Two hours later, he’s off to join them. He summons Mandat to the Commune, has the commander arrested and, shortly after, shot. At home, Gabrielle asks Lucile and Louise, “What are English overcoats?”

At 6 a.m., Louis inspects the National Guard, and the three women on the Rue Cordelier change apartments. By 7.30, the big guns are trained on the palace, Camille is asleep, and Danton is trying to get the king out of the palace alive. Louis abandons the Tuileries and seeks refuge at the Assembly.

Camile and Fréron witness a mob slaughter a captured royalist patrol. Anne Théroigne is in the crowd, and Camille sees her kill Louis Suleau. They return home to Lucile, who has been spat at in the street, and carries “a three-inch blade for comfort.” Gabrielle is assaulted by the local baker when she tries to get home.

Past midday, a patriotic Cordelier gives the three women the Queen’s hairbrush, a moment from the Tuileries. Late afternoon, Danton comes home to sleep. Meanwhile, the Assembly is in permanent session. Camille is there to keep an eye on the Girondists. Danton will be invited into government. The king will be suspended. Outside, they are burning the bodies.

It is 11 August 1792. “Long live the republic.”

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then I recommend listening to:

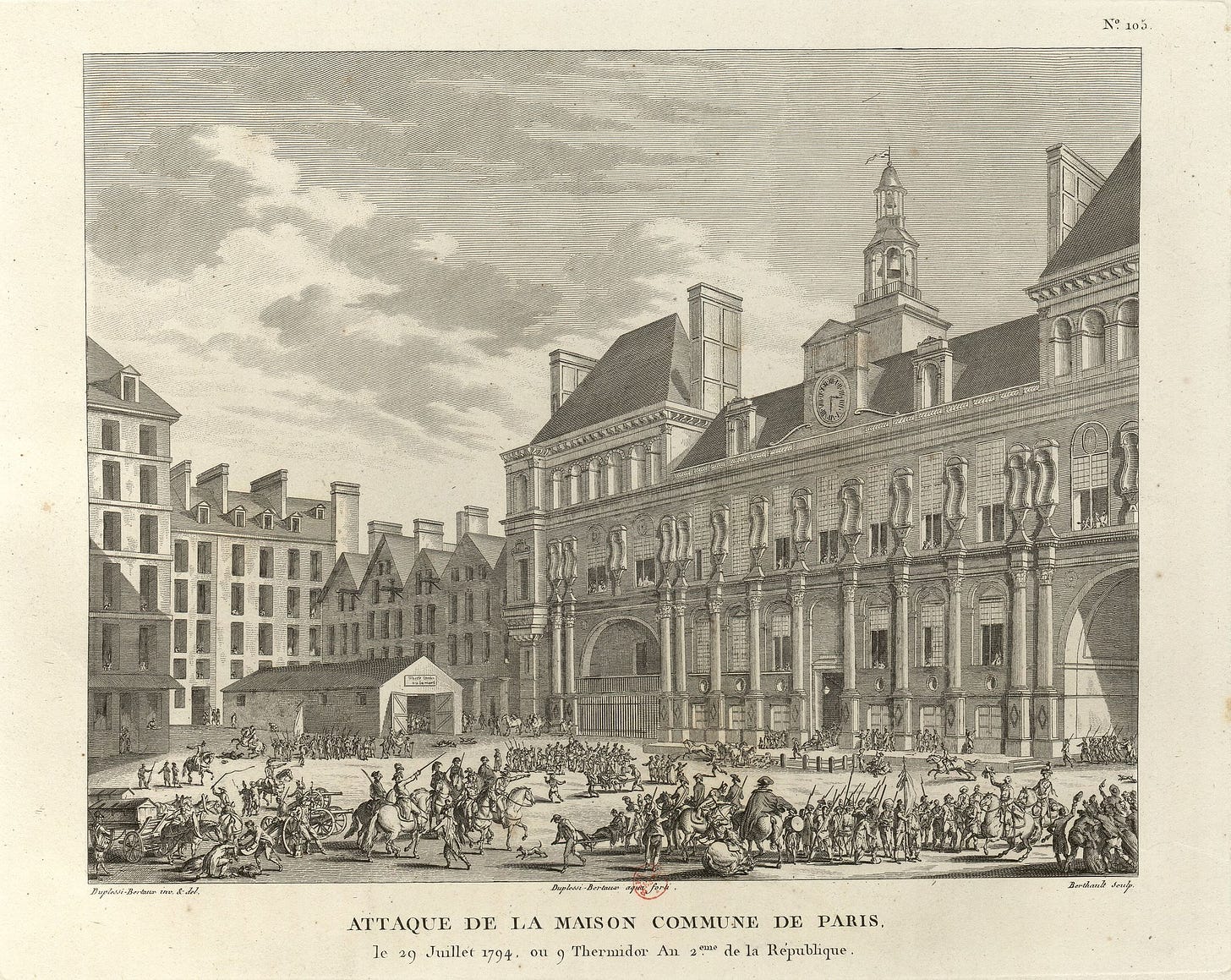

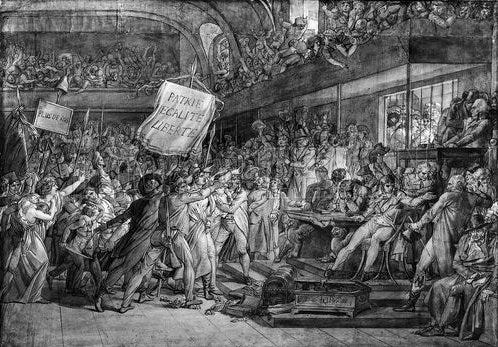

This week covers the events of the 10 August Insurrection, which overthrew the constitutional monarchy of Louis XVI and the Legislative Assembly. This is sometimes referred to as the Second Revolution, marking the beginning of a much bloodier and tumultuous period of the revolution.

Not mentioned in Mantel’s narrative is the surge in sugar prices, caused by the slave revolt and revolution in Haiti. Like the rising price of bread in 1789, this was…ahem, souring the mood in the summer of 1792. But much worse was the prospect of the Brunswick and hordes of Austrians and Prussians descending on the capital. The mood in Paris was tense!

Add to this the king dismissing his Jacobin ministers, an angry demonstration inside the Tuileries on 20 June, General Lafayette abandoning his post to try and quash the sans-culottes, and Danton and the Cordeliers organising the radical Sections into a shadowy alternative to the government at City Hall. Every day, more radical volunteers and fédérés arrive in the city. Everything is heading towards a showdown between royalists and republicans.

Footnotes

1. Danton O'Clock

'Will you stop being so bloody hearty?' Camille asked. 'You make me feel sick.'

Mantel playfully opens the chapter with Danton “gone” again, his fellow revolutionaries in blind panic because they cannot go on without him. Lucile is coolly reading a novel and eating an orange. She tells Fabre to get Robespierre: “He is such a steadying influence when Camille is killing himself.”

But of course, Danton has not run away. He’s back and counting the hours down to Danton O’Clock. Danton’s revolution. Because 1789 was Lafayette’s revolution, Mirabeau’s revolution. And this is his, and he wants to keep Robespierre well away from proceedings:

‘… keep him out of my way. I don’t want him at my elbow tonight. I may have to do things that will offend his delicate sense of propriety.’ He paused. ‘We can count the hours now.’

Danton’s revolution is going to be planned, decisive and violent. In fact, this is the first moment in our story where something genuinely planned and revolutionary takes place. Everything up to 10 August has happened accidentally and chaotically.

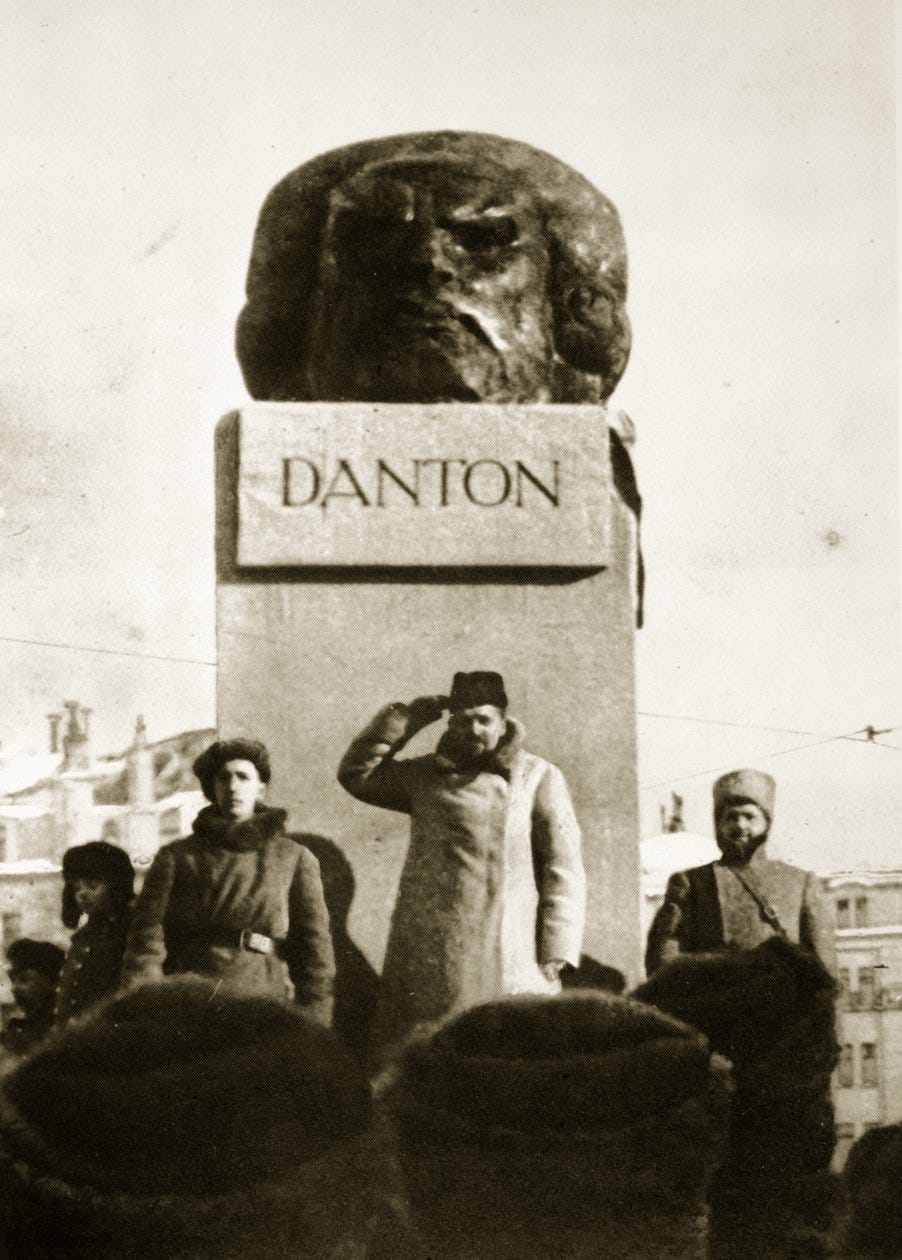

10 August is different. It is an organised insurrection aimed at overthrowing the monarchy and the French government. It should be no surprise that Danton was a massive inspiration to Vladimir Lenin and the Russian Revolution of 1917. In October 1917, Lenin quoted Friedrich Engels (misattributing the quote to Karl Max):

Marx summed up the lessons of all revolutions in respect to armed uprising in the words of “Danton, the greatest master of revolutionary policy yet known: de l'audace, de l'audace, encore de l'audace “

Audacity, audacity, and more audacity.

As Brissot grimly observes at the end of the chapter, “I’m told he’s their man. They’re yelling their throats out for him.” But if he is the hero of the hour, the “man of action” as Marat puts it, Mantel shows us all sides. Putting his affairs in order, getting some sleep, coldly authorising an assassination, the bully drunk on power:

‘Keep refusing, Mandat,’ he said, and began to drag him towards the Throne Room, where the new Commune had assembled. He laughed. It was like being a child again – the licensed brutality, whne the issues are simpe.

2. Goodbye, Suleau

‘Be very careful, because you notice that as the Revolution goes on there are new crimes.’

It’s Camille’s blessing and curse to have friends of all kinds. We met Louis Suleau in the first week, “Life as a Battlefield”:

There will be a war in our lifetime, he told Camille, and you and I will be on different sides. So let us be fond of each other, while we may.

Both become journalists. In his The Acts of the Apostles, Suleau writes unpleasant awful things about Camille’s revoltuonary associates, especially the women – including Anne Théroigne. You can read an example here:

Once again, this chapter clearly delineates the three patriots: Danton takes no unnecessary risks to rise to the top; Robespierre keeps low to protect his conscience; and Camille tries to kill himself in bed and on the streets, while trying to save a friend from the Revolution he helped unleash.

It is interesting that Mantel has Camille Desmoulins witness Anne Théroigne’s murder of Louis Suleau. Both revolutionaries were there, but Théroigne’s role in Suleau’s death is disputed.

We have already seen how Desmoulins and Théroigne’s roles have been inflated be hearsay. And some of the stories about Théroigne were spread by her opponents to turn her into the blood-soaked Amazon of their fears and fantasies.

Mantel sacrifices some of the ambiguity and subtlety between reality and reputation in order to develop the antagonism between once-allies Camille and Anne. I’m not sure whether this is necessary: couldn’t Camille hear and believe this story second-hand?

3. Goodnight, M. Capet

They followed Louis's slumped shoulders, arranging themselves to enter the bedchamber in the due order. But the King turned to them his pale, full, anxious face – and slammed the door on them.

On his last night of liberty, Louis goes to bed alone. Not so unusual for regular humans, but the Kings of France did not just “get up” and “go to bed.” They participated in the elaborate ceremonies of the grande entrée and the coucher, where dozens of noble courtiers would watch the dressing and undressing of their monarch.

Not tonight.

4. De facto Danton

Gabrielle: ‘What does de facto mean?’ 'It means they'll do it now and make it legal later,' Lucile said.

In July 1792, the radical districts of Paris are preparing to overthrow the government. Danton is their leader, and the volunteer soldiers arriving daily from the provinces are reporting to him and not Lafayette’s successor Mandat, commander of the National Guard.

These radical Sections abolish the distinction between active and passive citizenship that has existed since 1789. Now, all men can join the National Guard and are encouraged to do so. The political clubs demand the king’s dethronement, but the Legislative Assembly refuses to debate the matter.

‘Will they ring the tocsin?’ Lucile asked. 'Yes. Very soon.'

The tocsin was the signal to begin the insurrection. The Paris Commune is replaced by the Insurrectionary Commune, and Danton’s rebel National Guard take control of the city. When Mandat tries to prevent the insurrection, he is summoned to City Hall, arrested and promptly murdered.

He nodded to Rossignol. Rossignol leaned out of the window and show Mandat dead.

Jean Antoine Rossignol is a soldier who was present at the fall of the Bastille and will later be a general in the Revolutionary Wars. His contemporary, the journalist and historian Louis-Marie Prudhomme claimed Rossignol ordered Mandat’s assassination. Mantel makes Danton ultimately responsible. Last week, he told Pétion that they must kill Mandat for, “The dead can’t come back.”

The men Lafayette once called “enthusiasts for murder” are now the government of France.

5. Murder in the garden

But it was impossible to describe all the acts of wanten horor that happened this day…

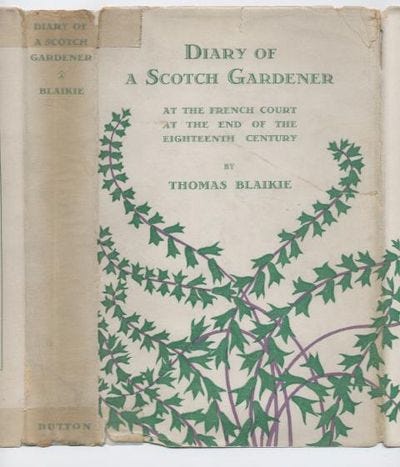

Thomas Blaikie was born near Edinburgh in 1750. He was a botanist on expeditions to the Alps in the 1770s, after which he worked as a gardener at the French court. He had been employed by the king’s younger brother, the Comte d'Artois, who is now in exile and will later become Charles X. He also designed the Winter Garden at the Parc Monceau for our old friend, Philippe, Duke of Orléans.

Unsurprisingly, the revolution was bad news for this royal gardener. After the restoration, the new Duke of Orléans granted him a royal pension. He died at home in 1838 in Paris.

6. ‘There are bodies’

‘I don’t think even the Swiss Guard knows the King has gone and I’m sure the people attacking the palace don’t know. I’m not sure if we’re supposed to tell them.’

As Fréron says, Camille is “not cut out for all of this.” After witnessing his friend’s murder, he goes to change his blood-stained clothes. Meanwhile, there is a massacre at the Tuilleries.

Not only has the king abandoned the palace, but he’s signed a note ordering the Swiss Guard to surrender. They withdraw into the gardens, where several hundred are killed. As she often does, Mantel emphasises the role of rumour as the news reaches the Assembly: “Fires had been started, and there were the usual dubious reports of cannibalism.”

Here is how the news was reported in London, in The Observer, 19 August 1792:

The English messenger, who left Paris on Sunday is positive, that he saw at least 6,000 or 7,000 persons lying dead in the streets of Paris; so that the slaughter must have been still more considerable than we stated it, which was 5,000; while others of our contemporaries sunk it so low as 12 or 1,500. There is reason to apprehend however, that the work of death will not end even here, enormous as are already the crimes of Frenchmen. For the King and his family, the most deplorable and melancholy fate may be, we fear too justly, anticipated.

In addition to the horrid excesses already detailed, the mob have broke into all the prisons at Orleans, and massacred the unfortunate prisoners in cold blood.

In reading such details, which freeze the generous heart with horror, one is led to exclaim – In what are these enormities to end?

French monarchy overthrown: king and family imprisoned – archive, 1792 (The Guardian)

Storming of the Tuileries Palace (World History Encyclopedia)

7. English overcoats

'What are English overcoats?' Gabrielle said, looking glassily from one to the other. 'Oh really!' Louise was scornful. 'What does de facto mean? What are English overcoats? Right little noble savage we've got here, Lucile?'

I love the triple act Gabrielle, Louise, and Lucile play in this chapter, while their husbands are away, tearing down the French government.

Gabrielle does not know that an English overcoat (capote anglaise) is a condom. The English called them French Letters, because the French invented sex, as far as the English are concerned.

Why Letters? Possibly because early condoms were made from animal bladders or intestines, and when dried, had the appearance of paper. One theory is that young Casanovas on the Grand Tour sent them home by post. Nice.

Speaking of Giacomo Casanova, the Italian adventurer described them as “English frock coats” and encountered them in brothels where they were used as protection from venereal disease. The first known description of a condom is in Gabriele Falloppio’s De Morbo Gallico (1574) on "The French Disease" or syphilis, which French armies brought into Italy in the late sixteenth century. Syphilis may have originated in the Americas, arriving in Europe as part of the Columbian exchange of animals, plants and diseases between the two worlds.

Louise Robert is enlightened on the matter: “It’s either you get pregnant, or you use English overcoats, don’t you, take your choice.” Gabrielle’s ignorance and Lucile’s pointed remark that married men like Danton won’t consider contraception may remind us of Robespierre’s unfortunate mother, who was always pregnant and died in childbirth.

'The way things are going,' Louise said, 'you'll have eight, nine, ten. When's it due?' 'February, I think. It seems such a long way off.'

Condoms: Its History and Use in the 1700 and 1800s (paywall)

The story of the condom (Indian Journal of Urology)

History of condoms from animal to rubber (Wellcome Collection)

8. Long live the republic

'There are petitioners here asking for the suspension of the monarchy. The Assembly will decree it. And the calling of a National Convention, to draw up a constition for the republic. I think now you can go and get some sleep.'

Vergniaud was the finest orator of the short-lived Legislative Assembly. He had begun as a defender of the constitutional monarchy. He now steps up to the podium to announce the monarchy’s suspension and a National Convention to replace the now-dead 1791 constitution. We have reached the First Republic.

Vergniaud is a Girondist, and the Insurrection returns Brissot’s Girondist ministers to government. However, with one significant difference: Danton will be the Minister for Justice. His Insurrectionary Commune now has the “whip-hand”, and it is Danton, not Brissot or Roland or Vergniaud, who is really in charge of government.

Back in Week 1, his sister asked Danton, “What do you want out of life?”

'To get on in it.' 'What does that mean?' 'I suppose it means I want to get a position, to have monehy, to make people respect me. I'm sorry, I see no point in being mealy-mouthed about it. I jsut want to be somebody.'

He told Camille, “whatever you’re doing you have to get to the top.” That was Danton’s Theory of Ambition.

Now, he is at the top. Where does one go from here?

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Five, Chapter I. Conspirators (1792).

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

I missed the orange while I was reading the chapter and am glad I did, because an orange in August calls for a great deal of suspension of disbelief. Plants are perhaps the most treacherous anachronism trap for historical novelists….

The insurrection of 10 August with the attack on the Tuileries was just terrifying. I watched 6 January 2020 live on TV, and even though the latter event was, by a stroke of good fortune, far less bloody, it reminded me a lot of that event. A good reminder that the times we live in are just as chaotic …

Just popped briefly into a Thomas Blaikie rabbit hole. I liked his description of events (and, the historical lexicographer in me enjoys his loose relationship with spelling - v typical in those days). I wonder if I can track down a copy of his diary - contemporary accounts by more accidental observers are always fascinating, I think. More so often than the "official" record - they really bring the reader into the heart of events.

Christopher Hibbert gives us Blaikie's account of the crowd bringing the King and Queen to Paris back in 1789:

"The Queen sat at the bottom of the coach with the Dauphin on her knees... while some of the blackguards in the rabble were firing their guns over her head. As I stood by the coach one man fired over the Queen's head. I told him to desist but he said he would continue."

He grew up at his parents' market garden on Corstorphine Hill, then in the countryside, but now swallowed up by Edinburgh. It lay on the site of what is now Edinburgh Zoo, and apparently there's a memorial plaque to him there.