APOGS #11: More complications

Part Four, Chapter III. Three Blades, Two in Reserve & Chapter IV. The Tactics of a Bull

It just shows, doesn’t it, how much worse things can get when you think you’ve hit rock-bottom? Life has more complications in store than you can ever formulate or imagine.

last week | main page | reading schedule | cast of characters | further resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings. And for the full experience, read online.

This week, we are reading Part Four, Chapter III. Three Blades, Two in Reserve & Chapter IV. The Tactics of a Bull.

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

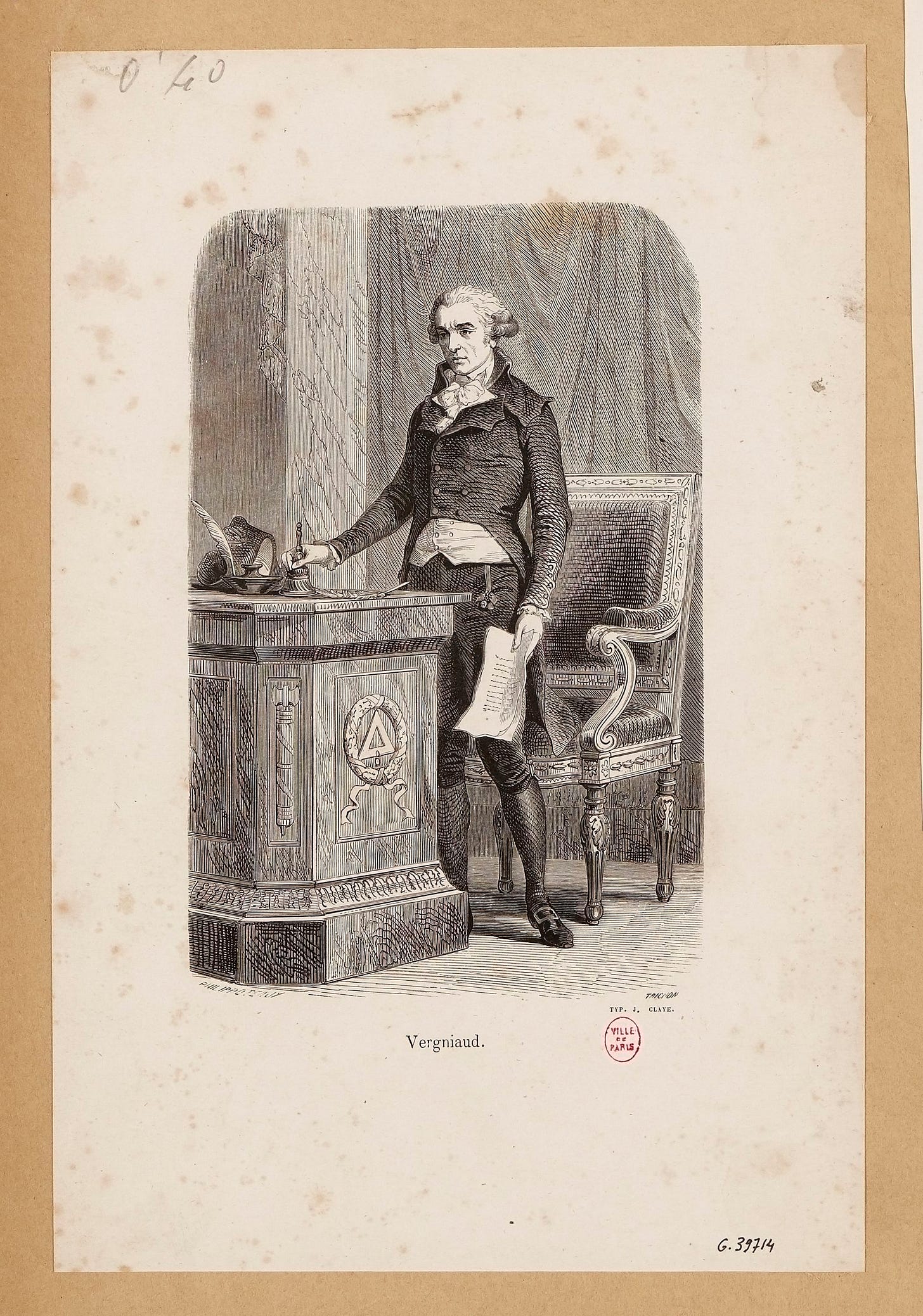

Spring, 1792. Gabrielle Danton gives birth to a baby boy; Leopold of Austria dies; the Fuellant ministry falls. The royalist ministers are replaced by Jacobins, men close to Brissot and in favour of war. Jean-Marie Roland is appointed Minister for the Interior. Danton is appalled and tries to talk Vergniaud round to joining his disreputable band of butchers and failed actors.

Camille considers breaking with Danton and Robespierre and supporting the war. A new method of execution is unveiled. It “can have your head off in a flash and you won’t suffer at all,” says Dr Guillotin. Robespierre interrupts Danton with Lucile Desmoulins. These men are cold towards one another, but at the Jacobin Club, Danton the demagogue has despot Max’s back.

Madame Roland is in power, so Danton and Fabre have to court her. But she is Brissotin, an unintentional traitor, if you ask Max. In the pay of the court, says Camille. But a republican nonetheless, says Danton. She hates Louis and his wife.

Gabrielle lives without illusions: her husband is sleeping with Lucile. Her apartment is full of strange people, her life is full of complications. In June, the king dismisses the “Patriotic Ministry” and a mob enters the Tuileries and terrifies the royal family. Lafayette calls for the suppression of the revolutionary clubs. Danton threatens to tear him to pieces.

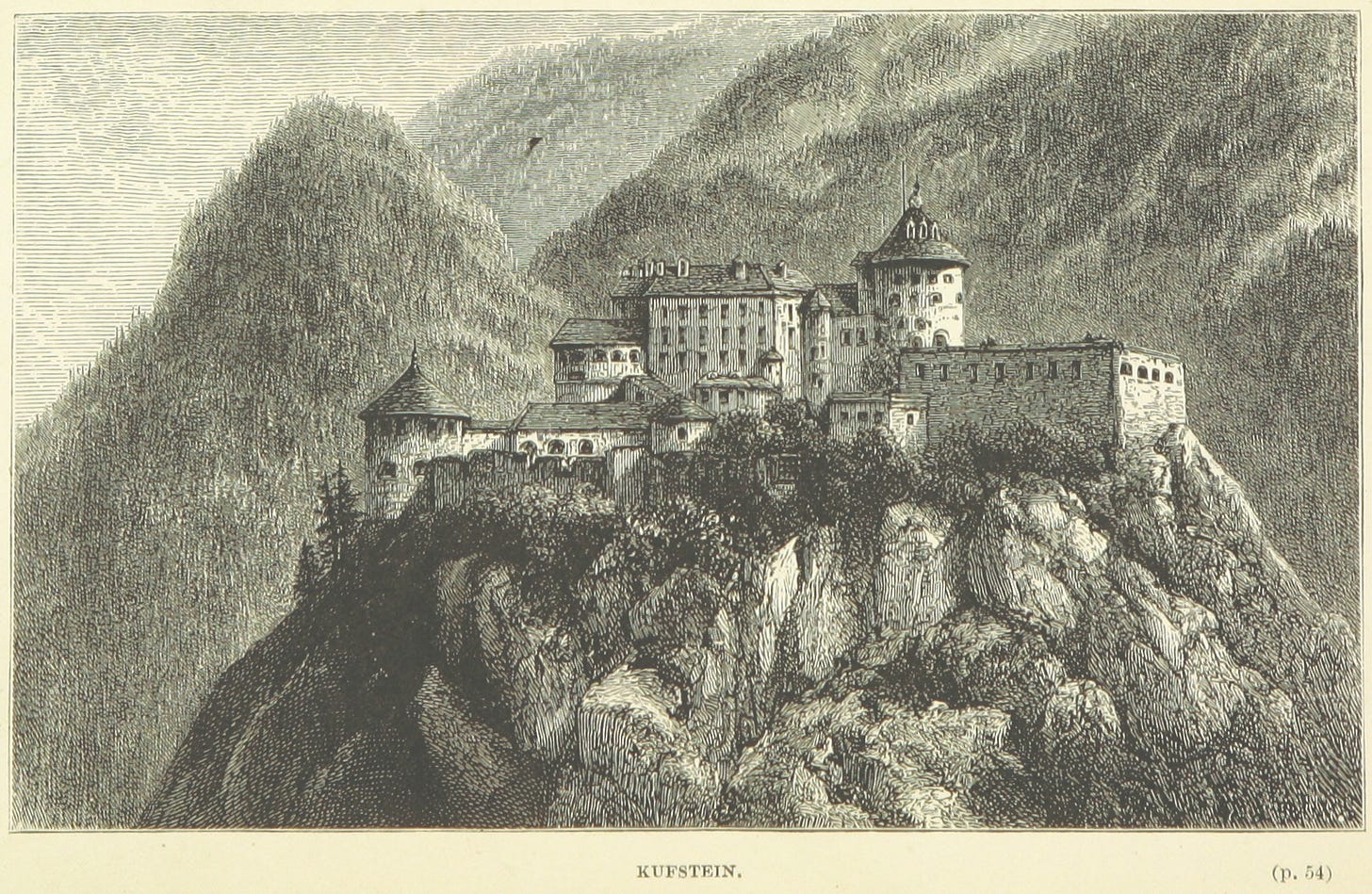

Anne Théroigne is back from an Austrian prison to avail herself of the Desmoulins blue chaise-longue. Lucile recommends she get out of Paris. The Cordeliers make themselves scarce until Lafayette has been and gone, and Danton begins to plan an insurrection. At the Duplays, Camille resists an act of seduction while in the rue Cordeliers, he and Lucile become parents of a son.

Phillipe, Duke of Orléans, throws his lot in with Danton, his last hope of unseating his cousin and becoming king. Danton has other ideas. The Duke of Brunswick plans to march on Paris and annihilate the Revolution. So now, the two Jacobin factions unite to begin again and make a republic.

DANTON: What do you mean, remove him? Kill him, man, kill him. The dead can’t come back.

[Silence.]

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then I recommend listening to:

22. War

In 1792, we’re living (briefly) in the Kingdom of France, a constitutional monarchy with Louis XVI as our head of state. He can appoint his ministers of government, but laws are made over in the Legislative Assembly. It’s there where Brissot begins beating the drums for a revolutionary war against the Holy Roman Emperor, Leopold II.

The king’s Feuillant ministry is opposed to this war, and in March, the pro-war Girondins put their men into the top jobs. Leopold dies and is replaced by his son Francis and, in April, France goes to war. On paper, this is a new kind of conflict, targeting the Austrian and Hungarian monarchies and vowing to liberate the people of Europe.

After the first initial defeats, the French murder one of their own generals, Théobald Dillon, leading to officers deserting the army en masse. Brissot blames setbacks on an aristocratic conspiracy led by a shadowy “Austrian Committee” orchestrated by Marie Antoinette. Lafayette and other generals make peace overtures, fuelling paranoia in Paris.

Fearing a counter-revolution, Manon Roland convinces her husband, now Minister for the Interior, to establish a military force near the capital to protect it. The king hesitates over approving this measure, and Jean-Marie Roland writes a disrespectful letter to the king, probably with his wife’s help. The king sacks Roland and the other Girondist ministers.

In response, on 20 June, an armed mob invades the Tuilleries, holding the king captive for several hours. The riot alarms the moderates, and a week later, Lafayette is in town, calling for volunteers to suppress the radical sections and political clubs. He flees the city and is burned in effigy as a traitor to the revolution.

On 25 July 1792, the commander of the Austrian and Prussian army, Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick, publishes a manifesto threatening Paris with annihilation if anything happens to the royal family. The Brunswick Manifesto helps galvanise the radical sections and precipitate a second French Revolution in August 1792.

Footnotes

1. Three Blades, Two in Reserve

What do you make of this chapter’s title? What are the three blades?

I assume that one of the blades “in reserve” is the newly constructed guillotine, waiting in the wings to begin its business very soon. Is the other reserved blade Georges-Jacques Danton? He spends these two chapters biding his time, as the mood in the capital ripens for renewed revolution. Thoughts please.

Danton on Vergniaud:

‘Oh, but I like to see a man doing what he is good at.’

2. Caesar Maximilian

‘He is becoming morbidly suspicious,’ Pétion said. ‘I used to be his friend. Not to mince matters, I fear for his sanity.’

Our friend Max is not popular right now. He is an isolated voice against a popular war. Last year, he tried to abolish capital punishment. Charles-Henri Sanson, the public executioner, is satisfied his job is not in peril – even if a new invention appears to undermine his profession:

But that deep-thinking man, M. Sanson, feels that M. Robespieere is out of step with public opinion, on this point.

At the Jacobin Club, they heckle him and call him “Despot”, but Danton defends him as a despot of “pure reason.” In public, these men have each other’s backs. They flatter. But in private, their words are barbed. When Robespierre talks about how Horace “was forced to flatter Augustus”, Danton says, “Camille’s writings flatter you.”

It is a wounding comment. Augustus made himself the first Roman emperor and ended the republic. Only recently has Robespierre been warning that their current situation could lead to a military dictatorship under Lafayette.

His staunchest supporter is Camille Desmoulins, a debauched and disreputable pamphleteer. He tries hard not to think about his friend’s private life, a compartmentalisation that Danton finds amusing and irksome.

But Max now confuses his own willful ignorance with conspiracies against him:

Of course, they might be keeping things from him. People did tend to keep things from him.

‘You remind me - what’s the name of that English King?’

’George,’ Robespierre snapped.

’I think I mean Canute.’

King Canute was the eleventh-century Danish king who united England, Norway and Denmark into the North Sea Empire until his death in 1035.

Originally, a story was told of him attempting to hold back the tide, and upon getting his feet wet, discovering the limits of his royal power. Subsequent versions assume (more realistically) that Canute was well aware that he was not omnipotent and was demonstrating this fact to his nobles.

Camille uses the proverbial Canute to suggest that Max is trying to hold back the inevitable tide of war. Max would prefer the version where the king demonstrates he is just a man. That Robespierre believes men should be perfect, but not all-powerful, is an unresolved contradiction in himself and his Revolution.

CAMILLE: “I wonder, you know, what would happen to me if Danton and Robespierre ever disagreed?”

3. The National Razor

He is not to suffer, because in France the age of barbarism is over, superseded by a machine, approved by a committee.

And so it is here: Madame La Guillotine, the National Razor, The Silence Mill, The Capet Necktie, The Timbers of Justice. The Machine.

On April 25, 1792, Jacques Pelletier became the first person to be guillotined in Paris. The instrument is named after its chief advocate, Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, and not its inventor, Antoine Louis – though it briefly bore his name as the louisette.

The guillotine was considered a democratic and humane alternative to the system of the Ancien Régime, where only the nobility secured the quick death by decapitation. Commoners suffered the noose or worse. Between now and July 1794, about 17,000 people will be guillotined.

France abolished the death penalty in 1981. In 1977, Hamida Djandoubi was the last person to be executed by guillotine in France.

4. Women and the Revolution

In fact I had an idea that Camille was across the river, addressing one of these freakish women’s groups with which he and Marat are involved – Society of Young Ladies for Maiming Marquises, Fishwives for Democracy, you know the sort of thing.

Danton is predictably appalled by women in politics. Women are not regarded as active citizens and are barred from the floor and the podium at the Assembly and the Jacobin Club. But they are active elsewhere across the revolution, from the salons to the streets. In this novel, Madame Roland and Anne Théroigne embody these two extremes of activism. Roland will have “no women” at her salon, “with their chatter, their petty rivalries over their clothes.”

Anne Théroigne will not be silenced. She speaks at the Cordeliers, heckles the deputies from the public gallery in the Assembly, and supports mixed and female clubs and societies. She pays a high price for using her voice and is vilified in the royalist press, who call her the “patriots’ whore.”

One prominent royalist pamphleteer is Camille’s old school friend, Louis Suleau, whom we will meet again next week. “Why is Suleau at large?” Théroigne asks Lucile Desmoulins. “Why isn’t he dead?”

Women in the French Revolution, from the salons to the streets

Watch: Les femmes dans la Révolution française (In French)

5. Liberty Louis

The crowd filed past them and laughed at them, as if they were the freaks at a country fair. They made the King put on a ‘cap of liberty’. These people – people out of the gutter – passed the King cheap wine and made him drink from the bottle to the health of the nation. This went on for hours.

The demonstration on 20 June is a sign of things to come. Gabrielle is unhappy about it, and so will much of France. But France is not married to Danton, and Gabrielle’s husband intends to rise to power on the back of these “people out of the gutter.”

The “cap of liberty” is a Phrygian cap, a soft conical cap worn in the ancient world, which became associated with freed Roman slaves. The bonnet rouge became a symbol of the revolution and worn by Marianne, the personification of the French nation.

Working-class revolutionaries adopted the headgear as a symbol of equality and liberty. Not for them the powdered wigs of the aristocracy. And these sans-culottes (“without breeches”) are the militant partisans who are about to redirect the path of the Revolution.

In America, the liberty cap was incorporated into the seal of the United States Senate. But it was a contentious symbol in a country home to enslaved people. In 1854, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis blocked plans for a red-capped statue of liberty on the US Capitol Building, declaring that: “American liberty is original, and not the liberty of the freed slave.”

How the Phrygian cap became a symbol of liberty (History Extra)

CAMILLE: “We must begin again. We must stage a coup. We must depose Louis. We must take control. We must declare a republic. We must do it before the summer ends.”

6. A knitted god

Oh good heavens, Camille thought. This Max, he believes every word he says, ‘I wouldn’t presume to know what kind of society God intends. It sounds to me as if you’ve gone to a tailor to order your God. Or had him knitted, or something.’

Love Camille for this, and Max becomes more terrifying by the hour. Astute Wolf Crawlers will remember that this image is reprised by the French Ambassador in Wolf Hall, when he says of Henry VIII: “Do you wonder I tremble before him? My river. My city. My salvation, cut out and embroidered just for me. My personally tailored English god.”

7. La Marseillaise

They are hand-picked, staunch patriots, these Marseille men, marching to the capital for the Bastille celebrations; they march singing their new patriotic song, and their minds and jaws are set. A neat spearhead for the Sections, when the day comes.

In May, the Minister of War proposed to invite armed volunteers from the provinces to the capital, initially for the July anniversary of the revolution, but also to defend Paris and bolster the army. These fédérés or federates would transform the National Guard into a republican revolutionary force.

And they’ve got a song. On 25 April, Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle composed a song to rally the troops, who were then in retreat in the early stages of the war against Austria and Prussia. He called it the "War Song for the Army of the Rhine", but it was soon renamed after the fédérés from Marseille, who sang it as they marched into Paris.

In 1795, the National Convention will make “La Marseillaise” the first French national anthem. It was banned after the Bourbon restoration in 1814, but was restored as the national anthem in 1879.

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Four, Chapter V. Burning the Bodies.

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

I think my favourite passage this time (this week’s grim smile) was Lucille’s comment when Louise Théroigne wondered how Camille gets away with stuff (and don’t we all wonder?): “It’s a mystery. I suppose—you know how in families there’s usually one child who gets away with more than the others? Well, perhaps it’s like that in revolutions as well.” I think we all know what she means.

A minor thing to note but I loved how Mantel named her characters in the conversation between the Duke and de Sillery - at first mention they are the Duke of Orleans and the Comte de Genlis. Then, the Comte becomes de Sillery, and the Duke, Philippe. By the end of the exchange, de Sillery is Charles-Alexis, and they both seem thoroughly undressed and undone by their now-precarious ambitions to power. I don't presume to know the mind of Mantel, but the effects of all these little choices are pretty palpable!