APOGS #10: Live without illusions

Part Four, Chapter I. A Lucky Hand & Chapter II. Danton: His Portrait Made

As my sister Anne Madeleine says, people like us, we have our day; and when our day is over, and we are forgotten, they will be on the arms of other men. I like them, these girls. Because I like people who live without illusions.

last week | main page | reading schedule | cast of characters | further resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings. And for the full experience, read online.

This week, we are reading Part Four, Chapter I. A Lucky Hand & Chapter II. Danton: His Portrait Made.

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

DANTON: Don’t pretend to be shocked, or not more than is necessary for form ́s sake.

This week’s story

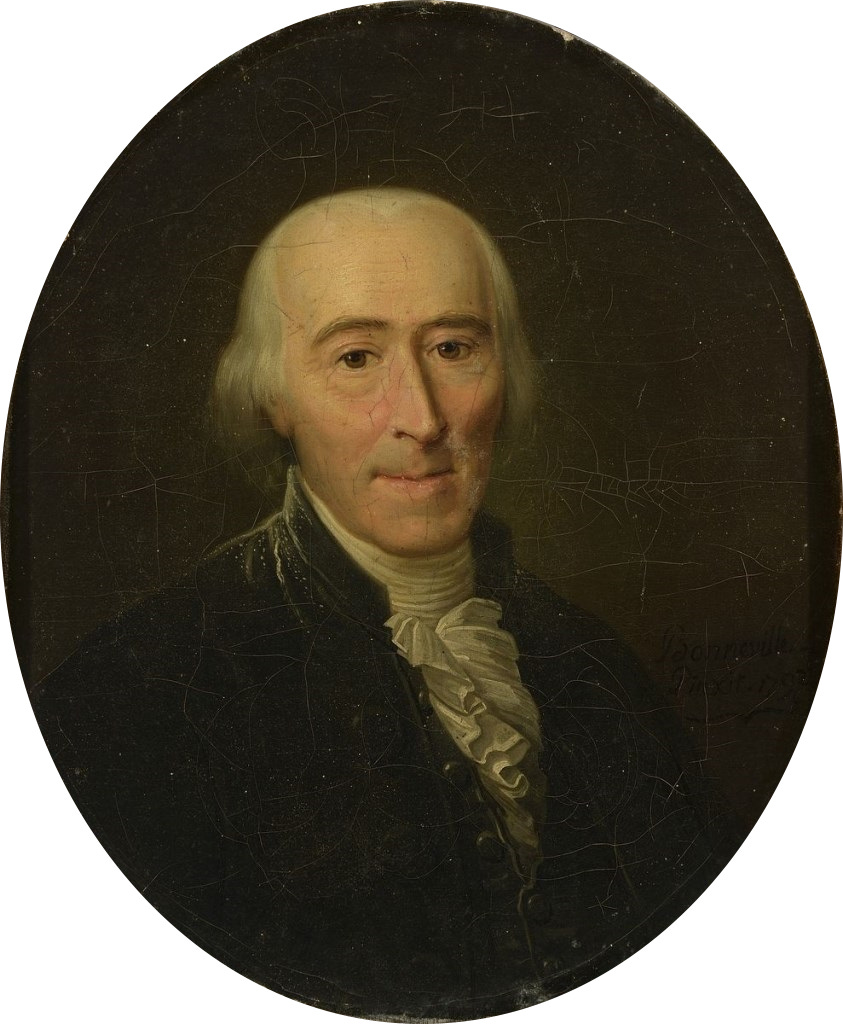

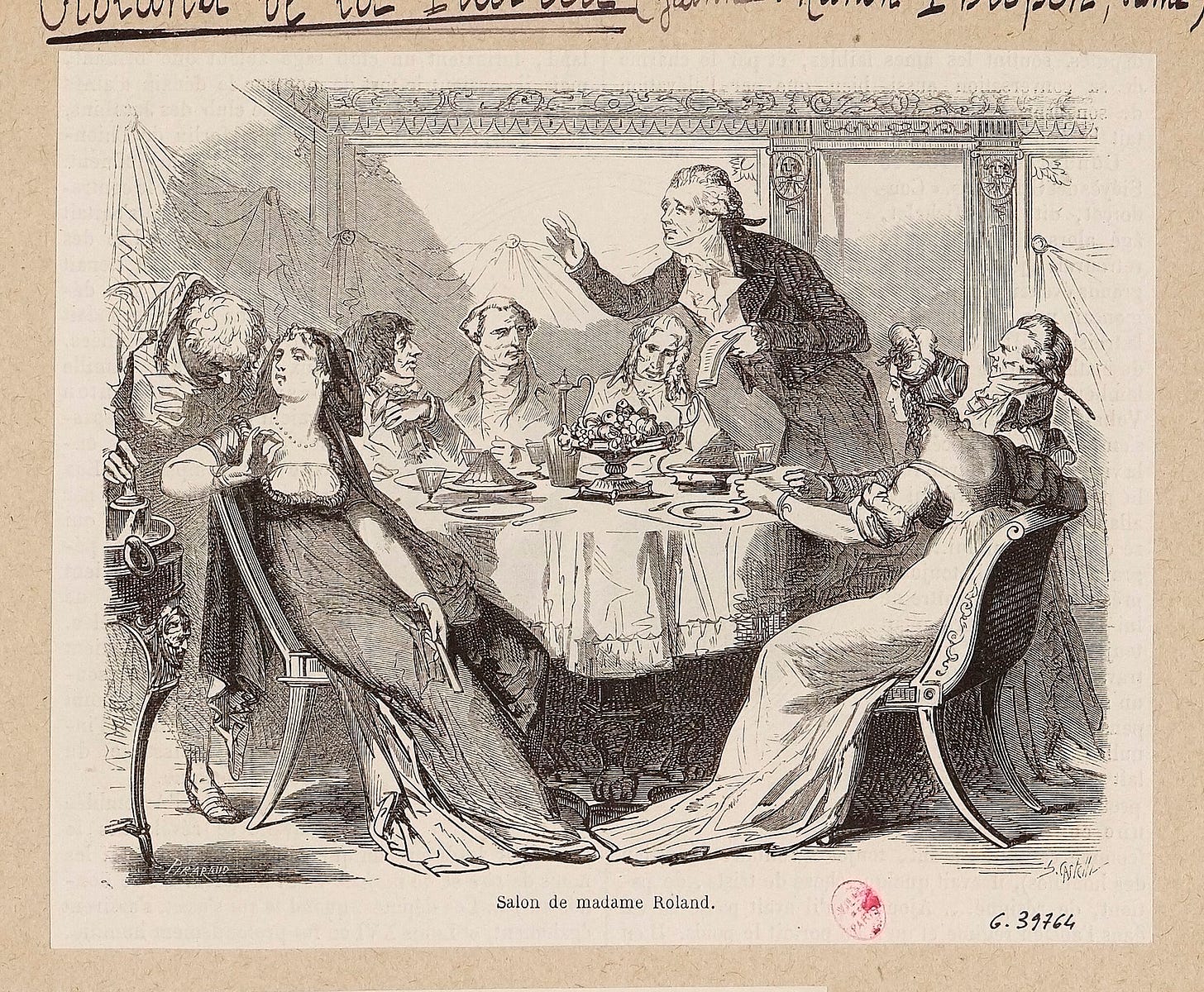

Manon Roland has moved from Lyon to Paris and set up a republican salon held each day between the close of business at the Assembly and the first speeches at the Jacobin Club. But who is Madame Roland?

We retrace her steps. Manon was the only surviving child of a Parisian engraver. She was intelligent, an autodidact, an enthusiast for Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Sexually assaulted by her father’s apprentice, she felt blameworthy for her inability to ever stop thinking about it.

In 1776, she met Jean-Marie, a kindly man, twenty years her senior. In 1780, they married and moved out of Paris. She helped her husband with his work, and outshone him in every way. She demanded a larger stage. In July 1789, that opportunity arrived. In 1791, they returned to Paris.

The National Assembly has been replaced by the Legislative Assembly. Madame Roland’s friend Brissot is now a deputy. Robespierre is rebuilding the Jacobin Club, and Camille has returned to the bar, using his legal cases as a soapbox for his controversial opinions.

And here is Danton to speak his mind. After the July massacre, an amnesty allowed him to return to Paris, where he failed to be elected to the new Assembly. He goes back to Arcis, and his sister tries to keep him there – but Paris is calling. In December 1791, he is elected to public office in the Paris Commune.

Danton considers the bellicose Brissot and his people, and Max Robespierre asks him to support his opposition to war with Austria. Danton visits Max’s new home at the carpenter Duplay’s. Danton considers the Desmoulins couple next door to him, and how he intends, at some point soon, to sleep with Lucille. Danton boasts of many sexual conquests, including the mistress of the Duke of Orléans. He predicts the Duke will soon need his friendship.

I think perhaps 1792 is my year.

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then I recommend listening to:

These two chapters cover the closing months of 1791. After the massacre of the Champ de Mars, the republican cause looks defeated. The triumvirate of Adrien Duport, Alexandre Lameth and Antoine Barnave has seized the initiative and is directing both the king and the National Assembly towards a constitutional monarchy.

Barnave and his band of liberals had walked out of the Jacobin Club to form the Feuillants society in defence of the new constitution. However, they adhered to new rules prohibiting political societies, and ran the Feuillants as a social club. Robespierre, meanwhile, ignores this prohibition and builds the Jacobins into a government-in-waiting.

The National Assembly is dissolved on 30 September 1791, having achieved its goal of creating a new constitution for France. It is replaced the following day by the Legislative Assembly. Deputies from the first assembly were barred from election to the new body. As a result, France’s new elected representatives are a younger group, more in touch with the mood in the provinces, and less impressed by the course of the revolution so far.

Chief among them is Deputy Jean-Pierre Brissot, an abolitionist and republican who now becomes the main advocate of war with Austria. Many of his allies are deputies from the département of Gironde in southwest France, so this emerging faction becomes known as the Girondins or Brissotins. Brissot favours a revolutionary war to unite France and eliminate opponents at home and abroad.

It is a popular idea in the Legislative Assembly, which presents Leopold II with an ultimatum to renounce hostile alliances and withdraw Austrian troops from the border. Austria ignored the ultimatum, and on 20 April 1792, the Assembly votes for war.

Footnotes

1. The Rolands

Here is Danton on the new people gathering around Jean-Pierre Brissot:

Last summer they used to meet at the apartment of an ageing nonentity called Roland, a provincial married to a much younger woman. The wife would be passably attractive, if it were not for her incessant Fervour … To my relief, I don’t know her very well.

“Lucky Hand” introduces us properly to a prolific writer of the Revolution, who will later be an opponent to our three main protagonists. Marie-Jeanne "Manon" Roland’s salon is a focal point for republicanism, but as we can see, she takes a dim view of our friends from the Cordeliers.

As well, she might. Mantel’s introduction of Manon as a point-of-view character is a smart move. She’s a stronger, more striking personality than Brissot, Pétion or Buzot. She gives us an identifiable stake in the survival of her faction when they become the target of attacks from Danton, Camille and Robespierre.

And we get to see the Cordeliers from the outside, through the hard gaze of a fiercely intelligent female autodidact. Her voice adds even further depth to this rich narrative:

Rejected, Danton had retired to his province to brood; and now he had decided he would like to become Deputy Public Prosecutor. With luck, there too he would be thwarted; the time was far distant (she hoped) when France would be governed by thugs.

Wrong on both counts. Danton is elected Deputy Public Prosecutor. And the thugocracy is just around the corner.

Further reading: A warning, the following links will inevitably contain spoilers as to the fates of Manon Roland and her husband.

Unseen, Even of Herself (The Paris Review)

Vive Madame Roland! (Aeon)

ROBESPIERRE: Spread the gospel? Well, ask yourself – who loves armed missionaries?

2. The Legislative Assembly

So, the National Assembly has been replaced by a new body. Thanks to Maximilien Robespierre's initiative, all the old deputies were barred from the Legislative Assembly. It will exist for a little less than a year before it and the monarchy are swept aside by a republican insurrection in the summer of 1792.

Of the 745 seats, 264 are filled by Feuillants, constitutional monarchists on the Right and led from outside the house by leaders like Lafayette and Antoine Barnave. On the Left sit 136 Jacobins and Cordeliers. They believe the king and queen are conspiring with émigré nobles and Austria to bring down the revolution. From these ranks, Jacques Pierre Brissot has emerged as a vocal proponent of a revolutionary war.

The remaining 345 deputies comprise The Marsh (Le Marais) or The Plain (La Plaine) and belong to no party or faction.

In debating war and foreign policy, Louis XVI believes the Legislative Assembly is overreaching its powers. War is the prerogative of kings. But as the cartoon above illustrates, France’s head of state is now little more than a prisoner to the Legislative Assembly.

The Legislative Assembly (Alpha History)

3. Playing for high stakes

‘No, Madame, I don’t believe in games of chance.’

There are many references to gambling this week. Like many idealists of the Revolution, Manon Roland disapproved of the gambling craze of the Ancien Régime. Her father had lost his fortune gambling in stocks and was living off her dowry when she was reading Rousseau and fantasising about “The Salon of Mme Roland.”

In 1774, the monarchy established the Loterie de L'École Militaire to fund the construction of a military academy on the Champ de Mars. This later became the Loterie Royale de France. “There would be no gambling, under the republic,” Manon thinks in “Lucky Hand.” And on 15 November 1793, the Revolution will ban the lottery, calling it a “scourge invented by despotism.” Manon will not be lucky enough to see this day.

Meanwhile, Danton tells us that “Camille gambles”, and the Desmoulins couple are

playing for high stakes, it seems to me, and each of them is watching the other for a failure of nerve; each waits for the other to throw down the hand.

Already, we can see the ideological divisions between the Girondists (Roland and Brissot) and their opponents. Camille is defending activity at a gambling house as a “matter of private morality.”

4. Danton speaks

Now we have a problem. It wasn’t envisaged that he should have part of the narrative. But time is pressing; the issues are multiplying, and in a little over two years he will be dead.

This chapter exhilarates: the frisson of first Mantel and then Danton turning their gaze to the reader and addressing us directly. This is one of the occasions when I have the uncanny sensation that this book is alive; and I have to put it down or find a place of greater safety, to keep it under lock and key.

Danton’s biographer David Lawday thinks he may have been dyslexic. While Camille “persecutes” blank paper with his black words, Danton becomes a relentless, thunderous orator. Remember Fabre’s advice to him at the start of the novel: “The whole trick’s in the breathing … you can go on for hours.”

Here’s Hilary Mantel on Danton’s lack of writing:

He had a brilliant oral memory, but avoided even writing letters, and Lawday speculates that nowadays we would have called him dyslexic. When he went to Paris, the lawyer who took him on as a clerk remarked that his handwriting was indecipherable; ça ne fait rien, Danton said haughtily, as he didn’t mean to make his living as a copyist. He preferred other people to put his thoughts on paper for him; then, of course, he could always repudiate them. Perhaps Lawday is right and there was some neurological glitch; the more jaundiced explanation is that he was secretive, and with good reason.

Others recorded some of these speeches, and you can read extracts of them here. But he wrote very little. Hilary Mantel was fascinated by “the gaps, the erasures, the silences” in the historical record. And behind Danton’s silence is a gigantic man with a booming voice. You wouldn’t be able to get away from it in Paris, 1791. So, of course, he must become “part of the narrative” and speak directly to us.

5. The incorruptible son of a carpenter

‘The Right try to present me as a fanatic. They’ll end up by making me one.’

Fearing for his life after the Champ de Mars massacre, Robespierre accepts the invitation of the carpenter, Maurice Duplay. Duplay’s humble house will be Max’s last home.

The Duplays worship him, collecting “portraits of their new son to decorate their walls.” He told Camille he was not the Revolution’s “man of destiny”, but there are now some who think he resembles that other famous carpenter son.

It is Madame Roland who calls Robespierre one of the “incorruptibles”, whose modest lifestyle and resistance to bribery made them the pure heart of the Revolution. By association, the eminently corruptible Camille and Danton can depend on their safety. Listen to Danton:

But if you ask Robespierre, he will vouch for my integrity. Nowadays that is the highest guarantee; because he is afraid of money, he is known as ‘the Incorruptible.’

6. The Girondists

Couthon’s spine is diseased, he has constant pain. Robespierre says this does not embitter him. Only Robespierre could believe this.

This quote about Georges Couthon reminds me of Mantel’s discussion of Henry VIII’s pain and its impact on his decisions. Mantel suffered from chronic pain during the writing of A Place of Greater Safety as a result of endometriosis and its treatment.

To my mind, this line betrays her sympathy for Danton (the honest hypocrite) and criticism of Robespierre (the incorruptible fanatic). As I mentioned in earlier posts, if this book has a message, it is that the personal is inextricably linked to the political; when we suppress this, we become monsters.

Couthon will become a friend of Robespierre’s, but he briefly flirted with the Girondists, “these people from Bordeaux,” led by Brissot. Many of these deputies come from the Gironde region in southwest France. Danton says they are not “anything so definite as a party”, but they see a lot of each other. And Robespierre wonders “about their motives.”

The antipathy between Danton, Robespierre and the Girondists will be one of the defining conflicts of the second half of the novel.

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Four, Chapter III. Three Blades, Two in Reserve & Chapter IV. The Tactics of a Bull.

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

One thing I'm finding interesting with both APOGS and the Wolf Crawl is the way you pick the quotations - they seem to be the ones that stick in my brain as well. This week there was an additional one for me in the Mme Roland section: "In the evening, she read classical history, and sat with closed eyes over the books, her hands still on the pages, dreaming of Liberty." There's a nice bit of foreshadowing there.

We really do get a view of how badly women are treated in these two chapters - both the young Mme Roland and the new wife Lucile are treated as commodities by men. The section with the old noblewoman manages to be comic while also making you think that some people were asking for trouble. (I was reminded of Lady Bracknell - and we all know her views of the French Revolution...)

The Danton section is a real eye opener. I've said previously that I find it difficult to differentiate between the leading men - but I now have a very clear view of Danton (and it's not a pleasant one). He's a self-centred, manipulative piece of work - and I wouldn't trust him as far as I could throw his hefty frame. It does make if difficult to understand why people followed him - he definitely doesn't have the same charm as Desmloulins. And you'd be thinking about him for a long time before the word 'incorruptible' popped into your mind.

I'm still finding it a bit of a challenge to work out whether some of the characters are walk-on parts or whether they will turn out to be significant (or even whether we've met them before) - but I suppose that's a bit like life.

And we're half way through. I'm impressed. Thanks, Simon, I don't think I would have managed it otherwise.

What a thing it was to encounter Mme Roland in her chapter—as you note here, it offered a welcomed contrast of both vantage point as well as tone, and in my eyes it is also a really well-developed portrait (tragically so) that offers a respite from the momentum that had been building. The line that really resonated with me here: "She dwelled—forced herself to dwell—on what was great in Man, on progress and nobility of spirit, on. brotherhood and self-sacrifice: on all the disembodied virtues." I feel like this captured her intentions but also the fallibility of all that is occurring in this Revolution, too, with the phrase "disembodied virtues" rendered ominous to me. (Is there a history behind that phrase?)

Also, I thought the depiction of Robespierre through the eyes of Danton was phenomenal—not only in its foreshadowing (not subtle!) but in how it takes the minimized voice and role of Max earlier in the book and uses this as a contrast that shows how he himself is evolving: "he spoke, if you follow me, as if it were beyond dispute." It seems to reveal the darkness of such devout conviction, no matter the benevolence of original intentions—and also how society sometimes sharpens the well-intended strong belief into one that is quite dangerous (and that's before digital algorithms made this sharpening all the more consequential in our current social media moment).

This image haunted me (and also was a great injection from Mantel's narrative voice): "So he went downstairs, the reasonable person, with his dog padding after him and growing at the shadows."

This was my favorite stretch of the book, without question, and it is hard to wait another week...