APOGS #9: Death will overtake you

Part Three, Chapter III. Lady’s Pleasure & Chapter IV. More Acts of the Apostles

… a few more days of indecision, and it will be too late to shake off your lethagy; death will overtake you in your sleep.

last week | main page | reading schedule | cast of characters | further resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings.

This week, we are reading Part Three, Chapter III. Lady’s Pleasure and Chapter IV. More Acts of the Apostles.

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

“Eighteen months of revolution, and securely under the heel of a new tyranny.” Marat tells us our days are numbered and the Austrians are coming. Camille says the Revolution was a conspiracy between the nobility and the English. Robespierre says we must always obey the law. It is 1791.

Our year begins with Lucile Desmoulins easing herself into married life with the Lanterne Attorney – scrutinised and slandered in the press – expecting the worst from the future.

One day in February, Robespierre drops by to remind Camille of his responsibilities. “You are unreliable,” he says. “You are dictatorial,” Lucile tells Max. That same day, Danton visits Mirabeau to secure the old man’s support for his political candidacy. He promises to be moderate.

Lucile learns the rumours about her husband and Maître Perrin. Camille does not deny them, and she wonders whether her marriage is a sham to protect his public image. He sidesteps the issue by taking her to the theatre.

Madame Roland and her husband arrive in Paris. Pétion and Brissot welcome her into their set; she shrugs off Danton’s clique. She will have a salon; she wants a republic, and it will come “soon.”

In March, Mirabeau dies. Now, everyone praises the hero of the Revolution, except Camille. Robespierre tells Camille that he will not marry Adèle Duplessis. “The Revolution is your bride,” says Camille. Danton puts it about that Max is sexually impotent.

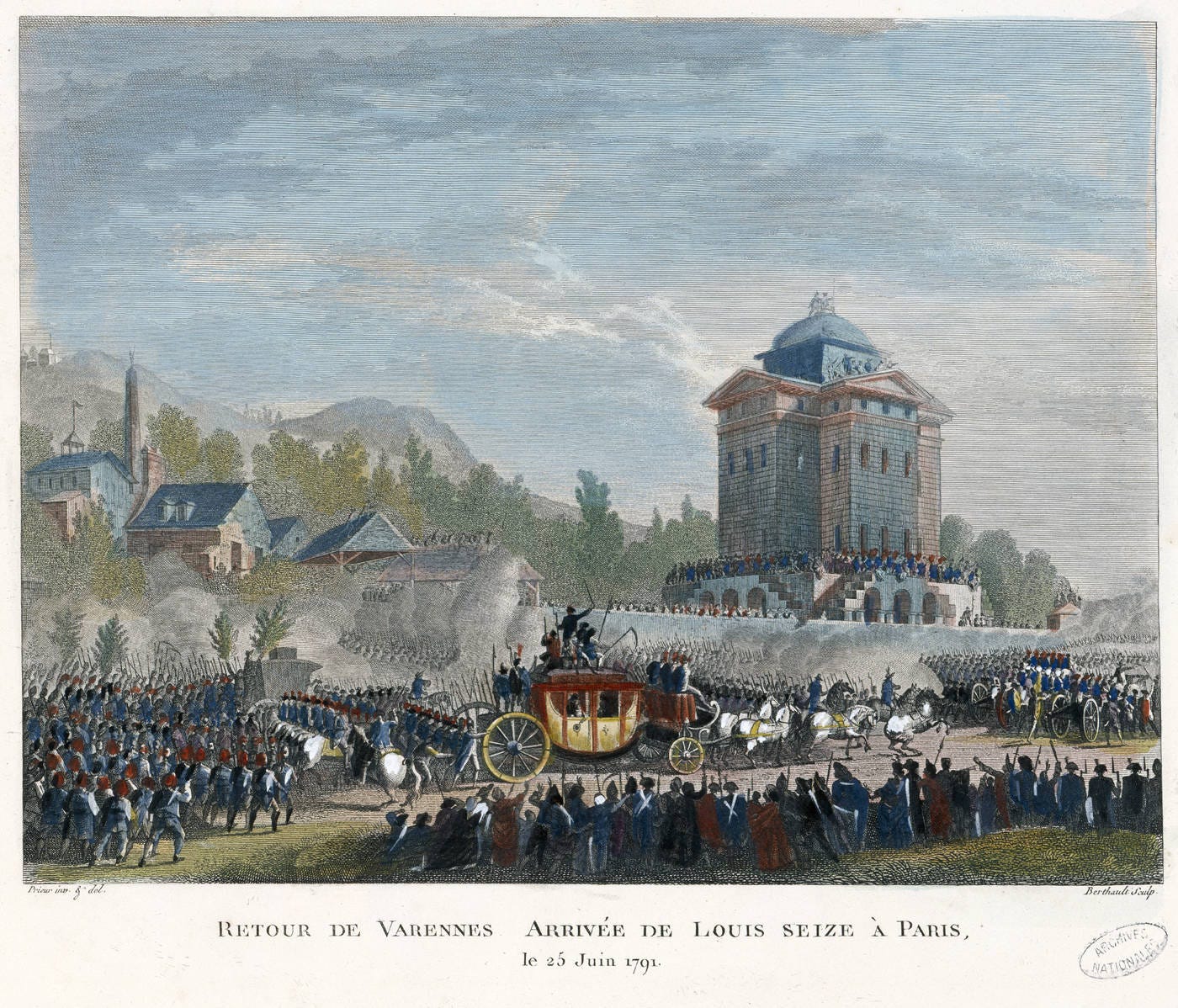

In June, the royal family attempt to escape Paris but are caught at Varennes. The Duke of Orléans positions himself to replace Louis, but Félicité de Genlis talks him out of it. Danton blames Lafayette and calls for a republic. The Cordeliers start a petition to demand the abolition of the monarchy and call for a demonstration at the Champs-de-Mars. Marat says Lafayette will fire on the people, Camille believes him, and Danton stays away. There is a massacre.

Now, the Cordeliers are on the run. In hiding, Danton tells Camille he will escape to England. On the streets, Robespierre narrowly escapes death, rescued by some enterprising women and a carpenter called Duplay.

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then I recommend listening to:

1791 begins with citizen king Louis XVI feeling increasingly despondent about his place in history, with Lafayette and Mirabeau competing for the role of national unifier and preserver of King and Revolution. Lafayette finds himself stuck in the middle, trusted by no one, as Mirabeau advises Louis to get out of Paris and wait for an opportune moment to return as the people’s hero, with Mirabeau at his side.

On 28 February, rioters attempt to destroy a prison at Vincennes, which they mistakenly believe is linked to the Tuileries Palace by an underground escape tunnel. Lafayette abandons the royal family at the Tuileries to quell the riot, and armed nobles arrive to protect the king. Lafayette escapes several attempts on his life, and both sides see their worst fears realised: an aristocratic counter-revolution and mob rule in the streets.

On 2 April, Mirabeau dies. Although he had been in the secret pay of the Court, he becomes the first hero of the Revolution, and the first person to be buried in the Panthéon.

On 20 June, the royal family finally attempt to escape Paris. They make it as far as Varennes. Riding back to Paris in the royal carriage, Antoine Barnave begins discussions with Marie Antoinette, replacing the deceased Mirabeau as the Court’s closest ally within the Revolution.

Barnave and the National Assembly uphold the useful fiction that the king had been abducted against his will. Danton and the Cordeliers lead the populist reaction to the National Assembly, arguing that the king can not be trusted and the monarchy should be abolished. Flaunting regulations against petitions and public assemblies, republicans gather on the Champ de Mars on 17 July. Dozens are killed when the National Guard opened fire.

Republican leaders are arrested or go into hiding, and the constitutional monarchists walk out of the Jacobin club, including the “triumvirate” of Adrien Duport, Alexandre Lameth and Antoine Barnave. They establish the Feuillant club, also known as the Society of the Friends of the Constitution, which will lead France and the Revolution for the next six months.

The Barrel spent his last few months in France pursuing the Lantern Attorney through the courts. He now hopes to pursue him, with an armed force, through the streets.

Footnotes

1. Axel von Fersen

The Swedish count fought alongside Lafayette in the American War of Independence and became a close friend of Marie Antoinette. There is no categorical evidence that they were lovers, but his intimacy with the queen caused jealousy and scandal at court.

He appears twice in this week’s chapters: Lafayette leaves a door open to incriminate the Queen and “pack her off home to Austria.” Later, the Duke of Orléans spots Fersen driving a carriage away from the Tuilleries.

After Fersen’s role in the royal getaway was made public, the count fled France and joined the aristocrat emigres, encouraging a foreign invasion of Revolutionary France.

2. Savage acts

The Pope pronounces the civil constitution schismatic. The head of a policeman is thrown into the carriage of the Papal Nuncio.

In a booth at the Palais-Royal, a male and female ‘savage’ exhibit themselves naked. They eat stones, babble in an unknown tongue and for a few small coins will copulate.

The civil constitution required priests to pledge an oath of allegiance to the king and country. This would help characterise the Revolution as anti-Catholic and help galvanise resistance outside of Paris. And so the head lopping continues in the name of Civilisation, while “savages” are exhibited at the Palais-Royal.

Thank you

for doing some digging here: the couple in question were French, pretending to be “savages” as cover for a sexual performance. You can read more about this here (in French) and the general licentious activities at the Palais Royal here (in German).However, this passage also made me think of the emergence of modern exhibitions of “exotic” and “savage” bodies. The eighteenth century saw the rise of freak shows, a topic explored in another of Mantel’s historical novels, The Giant, O’Brien, which is based on the life of Charles Byrne, exhibited in London in 1782. And into the ninteenth-century, thousands of non-Europeans were displayed, first as public spectacle and later as part of the development of scientific racism.

The best-known example was Saartje Baartman, a Khoekhoe woman from southern Africa who came to London in 1810 and was exhibited as the “Hottentot Venus.” In 1814, Baartman was sold to a French animal trainer who displayed her at the Palais-Royal in Paris.

She died the next year, aged 26, possibly from smallpox. The naturalist Georges Cuvier dissected Baartman’s body in defence of his theories of racial hierarchy. Her remains were still on display at Paris’s Musée de l'Homme in 1974. After his election in 1994, Nelson Mandela requested her repatriation. In 2002, Baartman was re-interred in South Africa, 192 years after Baartman had left for Europe.

Camille, a few feet away, looked like a gypsy who had mislaid his violin and had been searching for it in a hedgerow; he frustrated daily the best efforts of an expensive tailor, wearing his clothes as a subtle comment on the collapsing social order.

3. James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell

But he confined himself to an unspoken expletive when he saw her new set of engravings of the Life and Death of Maria Stuart. He did not like to look at these pictures at all. Bothwell had a ruthless, martial expression in his eye that reminded him of Antoine Saint-Just.

Bothwell was James Hepburn, the divisive third husband of Mary, Queen of Scots. He was accused of collaborating with her in the murder of her second husband, Lord Darnley. In a noble uprising against Mary, Bothwell fled to Scandinavia and the queen was forced to abdicate. She later escaped to England, where she was executed by her cousin, Queen Elizabeth, in 1587.

Camille thinks Bothwell looks a little like Antoine Saint-Just, the “miserable revolutionary” who will play a central role in the Lanterne Attorney’s own execution in 1794.

4. Le Père Duchesne

René Hébert was peddling his opinions now through the persona of a bluff, pipe-smoking man of the people, a fictious furnace-maker called Père Duchesne. The paper was vulgar, in every sense – simple-minded prose studded with obscenity.

Back in week 7, we saw René Hébert threatening to “write for the people in the street,” who Camille quips can’t read. Here, Hébert proves a man of his word, publishing a journal where “every other word” is an obscenity. La Père Duchesne will become the mouthpiece of the most violent rhetoric of the Revolution.

Père Duchesne was not Hébert’s invention; the name had been in circulation for a few years earlier as an everyman figure denouncing abuses and injustice. But Hébert will make this fictional character the loudest voice on the streets of Paris. Initially supportive of Lafayette and the monarchy, Père Duchesne became increasingly republican and bloodthirsty after the flight to Varennes and the Champ de Mars massacre.

Her emotions now seemed to lie just below the surface, scratching at her delicate skin to be hatched.

5. Liberté, égalité, fraternité

Robespierre declined to sit. ‘I won’t stay – I came to see if you’d written that piece you promised, about my pamphlet on the National Guard. I expected to see it in your last issue.’

On 5 December 1790, Robespierre delivered a speech at the National Assembly, proposing that the National Guard uniform be emblazoned with the motto “liberté, égalité, fraternité,” marking one of the first instances of this slogan. As we will see, the motto will soon be extended to “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity or Death." His proposal was rejected. As Camille says to Marat, “Just to know that he supports a motion is enough to make most of the deputies vote against it.”

They also voted against Robespierre’s proposal to admit passive citizens to the National Guard. Passive citizens are the non-propertied poor who helped make 1789 happen, but who are now being kept well away from the political process by the mob-fearing National Assembly.

Originally established to maintain order during the tumultuous days of 1789, the National Guard is now being deployed against the radical Cordeliers. As Danton notes this week, “There are patriots among the soldiers, but that old habit of blind obedience dies hard.”

6. Madame Roland

Her face glowed with excitement. ‘To be here – at last,’ she said. ‘For years I’ve watched, studied, fulminated, argued - with myself, of course; I’ve waited, longed, if I had any faith I would have prayed; all my concern has been that a republic should be established in France. Now here I am – in Paris – and it is going to happen.’ She smiled at the three men, showing her even white teeth, of which she was very proud. ‘And soon.’

OK, we’re going to get a whole chapter on Madame Roland next week, so I won’t say much here. Her writing is a key source for understanding life among the Jacobins of revolutionary Paris. Here we see her attach herself to Brissot and Pétion, leaders of what will soon become a faction advocating war with Austria.

Her future will be tied to theirs. She does not think much of Danton or Camille, who will later support Robespierre in opposing the war. Here, Mantel is preparing the ground for the two Jacobin factions that dominate the rest of the story: the pro-war Brissotins (or Girondins) and the Mountain, led by Georges-Jacques Danton and Maximilien Robespierre.

Vive Madame Roland! (Aeon)

7. Mirabeau’s funeral

“Go then, witless people, and postrate yourself before the tomb of this god of liars and thieves.”

Camille is not making himself popular by denouncing the first hero of the Revolution. Robespierre sees a son rebelling against his father; Camille regards it differently. Either way, the animosity seems personal and excessive, like everything else Camille Desmoulins.

Mirabeau becomes the first grand homme to be buried in the Panthéon, a national mausoleum modelled on the Roman Pantheon. What the revolutionaries didn’t know at the time was that Mirabeau had been working with the court to preserve the monarchy. He was on Louis XVI’s payroll, and the king had paid off his debts.

And by the time letters were discovered exposing Mirabeau’s complicity with the king, the revolution had radicalised and the monarchy was gone. Mirabeau went from hero to traitor; his body was disinterred and replaced by the remains of a certain Jean-Paul Marat. Here’s what the People’s Friend had to say about Mirabeau’s death at the time:

People, give thanks to the gods! Your most redoubtable enemy has fallen beneath the scythe of Fate. Riquetti (Mirabeau) is no more; he dies victim of his numerous treasons, victim of his too tardy scruples, victim of the barbarous foresight of his atrocious accomplices. … The life of Riquetti was stained by a thousand crimes; let a black veil henceforward cover the shameful fabric, since it can no longer injure you, and let the recital scandalise the living no more! But beware of prostituting your incense; keep your tears for your honest champions…

And here is what Madame Roland wrote:

I heard – but far too seldom – the astonishing Mirabeau, the only man in the Revolution who had the genius to sway men and to magnetise an Assembly; a great man in his abilities (though he had his faults), he stood head and shoulders above the rest and was the unquestioned master whenever he took the trouble to command. He died soon after. I thought at the time that this was timely for his reputation and for the cause of freedom, but subsequent events have taught me to regret him more. We needed the counterweight of such a man to oppose the depredations of a pack of curs and to save us from the domination of swindlers.

8. Lady’s pleasure

‘No one else is going to do what you are going to do, and you come to the point of renouncing, as much as you can, human needs and human weaknesses. I wish – I wish I could help you more.’

There is a nice bit of mirroring between the private lives of Max and Camille. There is the implication that Camille marries to avoid salacious accusations about his sexuality and love life. Robespierre doesn’t marry so that he remains incorruptible, immune to allegations of personal interest. Danton thinks they are equally perverse and denatured. Why can’t they do as he does? Marry, father children and have mistresses.

Gabrielle tried to meet his eyes for a moment. One day he noticed – as one notices rain clouds, or the time on the face of a clock – that he doesn’t love her now.

9. Flight to Varennes

‘Gentlemen, the King has fled in the night. Let us proceed to the Order of the Day.’

The king’s failed escape attempt is a watershed moment. Until this point, republicanism was the fringe opinion of people like Camille Desmoulins. Now, Danton joins him, bringing over the Cordeliers, but not yet the Jacobins. Robespierre asks pedantically, “What is a republic?”

The phrase “Order of the Day” has a dark resonance with the future. In 1793, Bertrand Barère will stand up in the National Convention and exclaim, “Let's make terror the order of the day.” That is where we are headed.

Back in 1791, the National Assembly sends two deputies to bring the royal family back to Paris. Antoine Barnave will become Marie Antoinette’s secret ally. Jérôme Pétion will not trust the queen one bit, and will support Brissot’s contention that there is an Austrian conspiracy against the Revolution, led by Marie Antoinette and her brother, the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II.

10. Massacre

Camille said, 'The patriots saw the petition as an opportunity. So, it seems, did Lafayette. He saw it as an opportunity for a massacre.' This, they knew, was a journalist talking. Real life is never so clear and crisp. But that would always be the word for it, in the years ahead: 'The Massacre on the Champs-de-Mars.'

As with the fall of the Bastille, Mantel races through the “massacre on the Champs-de-Mars” in one paragraph. She is far more interested in the events that surround it: the Cordeliers considering their next moves, a sleepless Gabrielle, François Robert in his cell.

For me, the most interesting bit here is Danton. As Camille said, “two years ago, Danton, it was all right for you to lock your door and work on your shipping case. But it’s a different matter now.” Then he calculated that the risks were too great, and took advantage as soon as the tide turned.

Now, he jumps. He judges that Paris will never forgive the king for trying to escape. He reckons they’ll love him for saying so.

‘We might lose everything,’ Danton said. But he had made his calculations: always, when he seemed to flare up for a moment into some unreasoning, sneering aggression, his mind was moving quite coldly, quite calmly, in a certain direction. Now his mind was made up. He was going to do it.

But everything goes south. And Danton feels the heat and heads for London. But he’ll be back. And when he is, he’ll be able to say “Danton’s back,” and make it look like it’s all part of the plan.

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Four, Chapter I. A Lucky Hand & Chapter II. Danton: His Portrait Made

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

It's wild to think a book where almost everyone loses their head could be this funny.

Mirabeau - the "old man - was 42 when he died. You may like to consider recalibrating your age ranges. That said, getting to 42 will soon be quite an achievement for our leading characters and anybody else involved in French politics.

I'm really enjoying the way Mantel foregrounds the women - and not just to tell us more about the men. The exchange between Lucile and Caro is a delight - it brought to mind Cicely and Gwendolen in 'The Importance of being Earnest' - and tells us a lot about both women.

And Adele's response to being jilted by Robespierre is perfect. She's not a woman who will have a fit of the vapours and waste away - I almost expected her to be banging out 'I Will Survive' on the spinet.

The major impression I'm left with - not surprisingly - is that the French Revolution wasn't planned, it was a series of chaotic developments. At any point, it could have gone in a variety of directions. There certainly wasn't a business plan because that would have started with a vision - and I don't think any management consultant would let you get away with just 'Change things' as a vision. It's clear that there are a number of completely different agendas, so nobody should be surprised when everything falls apart.

Something I find interesting - and I don't know if this is me or some brilliant writing by Mantel - but I'm left with an impression of Louise (not a good one I might add), but Marie Antoinette seems to be a shadowy presence. And, of course, that allows you to mould her to your own thoughts and preconceptions - which is also what revolutionary Paris does.

And about the escape: surely everybody knows that royalty shouldn't travel together. (OK, it's planes really, but the principle is the same.) Surely they may have had better chances if they'd split up.

I'm trying to stick to my own advice: don't get too attached to anybody, they will more than likely end up with their head in a basket.