APOGS #8: Extraordinary events

Part Three, Chapter II. Liberty, Gaiety, Royal Democracy (1790)

‘A pretty, intelligent woman who has original ideas should have a life full of extraordinary events.’

last week | main page | reading schedule | cast of characters | further resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings.

This week, we are reading Part Three, Chapter II. Liberty, Gaiety, Royal Democracy (1790).

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

“We are now in 1790.” In January, the National Guard attempt to arrest Dr Marat, but is blocked by a furious Danton who rules like the king of the Cordeliers. Gabrielle knows her husband thinks the People’s Friend is “scum” but he will protect anyone in his District.

The Dantons have a child in May. Antoine. George’s mother comes up to visit. She’s insufferable and dismayed. City Hall tries to get rid of the Cordeliers, but Danton’s going nowhere: they’ve set up a Club in the monastery, and anyone can speak. Even women. When the Dantons visit his family in Arcis, they think he’s an advisor to the king and ask, “What’s the Queen’s favourite colour?”

July. The city celebrates the anniversary of the Revolution, but the Dantons stay in their district so as not to watch “people kiss Lafayette’s boots.” Fashions change. Camille moves in around the corner from Danton – still no closer to marrying a Duplessis.

Claude Duplessis tries to set his daughters up with civil servants. Lucile and Adèle Duplessis mock the poems they are sent, while lusting after Camille and Robespierre. The two revolutionaries are also receiving mail: Camille ignores the duels and death threats; Robespierre meticulously responds to Paris’s poor, looking to him as their hero.

In May, Anne Théroigne leaves Paris, much to the relief of the misogynistic Danton. Camille’s school frenemy Louis Suleau turns up, with a royalist rag called the Acts of the Apostles. And another newcomer to the city: Antoine Saint-Just. Camille calls him “a miserable revolutionary.”

December 1790. Claude changes his mind and allows Lucile to wed Camille. There is the slight difficulty of finding a priest who will agree to marry the violently anti-clerical journalist. Annette gifts the married couple her mournfully unused chaise-longue, and the Desmoulins settle down to a quiet life next door to the Dantons.

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then I recommend listening to:

On 4 February 1790, the king made a conciliatory address to the National Assembly, accepting his new role as a citizen king in a constitutional monarchy. This ended all hope amongst arch-conservatives of a return to the status quo.

It also splintered the Left, sidelining the radical Jacobins in favour of a moderate faction led by the liberal aristocracy. This group formed the Society of 1789 and included the Mayor of Paris, Jean-Sylvain Bailly, and the commander of the National Guard, the Marquis de Lafayette.

1790 was their year. As far as they were concerned, the revolution was winding down. They upheld the distinction between active and passive citizens, limiting voting rights and access to political offices to men who owned property. Passive citizens were also expunged from the National Guard, making the new militia more conservative and more loyal to Lafayette.

The moderate Society of 1789 and the Jacobins disagreed on the role of the monarchy in the new order. But both factions were committed to overhauling the clergy and the nobility, the first and second estates. In the summer of 1790, the National Assembly abolished hereditary titles and effectively nationalised the church, with state salaries and an oath of allegiance to the nation.

In July, France celebrated the anniversary of the Revolution with a national festival, the Fête de la Fédération, which placed Lafayette and the constitutional monarchists centre stage, pledging their allegiance to the king and constitution.

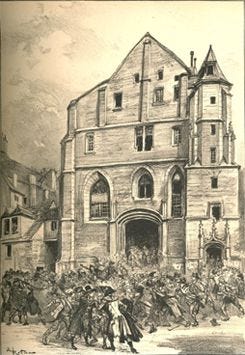

However, with the liberal aristocracy in control of the National Assembly, the National Guard, and the Paris Commune at City Hall, the capital’s radical revolutionaries began organising their opposition. Georges-Jacques Danton in the Cordeliers district set up the Cordeliers Club with a much lower entrance fee for membership than the Jacobins. The Cordeliers protected writers like Marat and Camille Desmoulins, who aimed their poison pens at City Hall, Mayor Bailly and Lafayette.

Footnotes

1. Mere women

‘Oh, we don’t have “mere women” any more. Last week your two prospective sons-in-law defeated me in argument. I am told that women are in every respect the equal of men. They only want opportunity.’

This chapter is the first with a first-person point of view. We get two of them, Gabrielle and Lucile. Mantel looks like she’s on the verge of following this with Robespierre’s perspective, but instead slyly reverts to third-person – as though there is an invisible shield deflecting any attempt to get inside the heads of our three male protagonists.

This chapter puts centre stage the role of women in the Revolution and in society. Thomas Jefferson has just helped Lafayette draw up “The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen”, which excluded women from citizenship, despite their crucial role in the march on Versailles. It’s time to quote Hamilton again, this time the Schuyler sisters:

We hold these truths to be self-evident

That all men are created equal

And when I meet Thomas Jefferson (unh!)

I'ma compel him to include women in the sequel (work!)

Indeed, in response to the Declaration, the playwright and activist Olympe de Gouges drew up “The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen” in 1791, declaring that “Women have the right to mount the scaffold, they must also have the right to mount the speaker's rostrum."

Gabrielle and Lucile’s narratives greatly enrich Mantel’s story and characterisation. Gabrielle’s life is “extraordinary”, but her response is no-nonsense and matter-of-fact:

[Danton] seemed to be away for hours. I just kept finding things to do. Picture it. You marry a lawyer. One day you find you’re living on a battlefield.

Gabrielle Danton is no advocate of women’s rights. And there’s no sisterhood loyalty from Lucile Duplessis either:

She was jealous of Théroigne. What gave her the right to be a pseudo-man, turning up at the Cordeliers and demanding the rostrum?

George-Jacques brandishes a misogyny that would have been uncontroversial in all but the most enlightened circles. For him, Camille’s love of “intelligent conversations with women” is “one of his perversions.”

2. On mother-in-laws and wallpaper

‘Paris is filthy, how can you bring a child up here?’

My favourite character in this chapter is Danton’s mum, Marie-Madeleine. You can tell she was a delight to write. Perhaps she’s a bit of a trope, but who cares – and I would love to know whether she actually visited her son and sat in the public gallery at the National Assembly.

Then she looked around and said, ‘This wallpaper must have cost a pretty penny.’

In several interviews, Mantel talks about the male critic who complained that there was too much about wallpaper in A Place of Greater Safety. Mantel retorted that there wasn’t nearly enough. She had this to say:

I think it's the fact that if a man wrote a book about a family, it was understood to have wider repercussions, to be a metaphorical representation, perhaps of the political process. If a woman wrote the same text, it would just be … a domestic novel.

We see this concern again in the Cromwell books: the integrated approach to her subject matter, refusing to separate public men from their private worlds, the rostrum from the chaise lounge. In an earlier chapter and essay, Robespierre attempts to separate the two:

Every citizen has a share in the sovereign power … and therefore cannot acquit his dearest friend, if the safety of the state requires his punishment.

Robespierre alone believes it is a virtue to sacrifice your friends for the General Will. It makes Danton “a bit uneasy … He does seem to set everyone very high standards.” Robespierre admits to having only one friend, Camille, and perhaps that is why he ultimately sacrifices him – to prove his incorruptible virtue.

By showing us the wallpaper and the chaise-longues, the mother-in-laws, and the love triangles, Mantel demonstrates that all these elements matter in linking private motivations and public actions. And she also exposes the monstrosity of the revolution’s obsession with the public rational citizen and its insistence on personal sacrifice to the General Will.

‘I should like to see the country governed by Danton and Robespierre. And I should be there to keep an eye on them.’ He smiled. ‘One may dream.’

3. The Cordeliers Club

I thought, how odd men are, at home they like to be comfortable but outside they pretend they don’t care.

And so Danton winds up leading the most radical Parisian political club, the Society of the Friends of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen – or the Cordeliers.

As the year progressed, revolutionaries were increasingly separating into two camps: the Left, who feared an aristocratic-led counterrevolution. And the Right, who believed in a constitutional monarchy and were terrified of the Parisian mob. The Cordeliers represented the very extreme of the Left, and embodied the mob that people like Lafayette feared. Gabrielle notes:

On the wall somebody had nailed a strip of calico with a slogan in red paint. It said, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.

This became their motto. It is the slogan most closely associated with the Revolution, and it may have been coined by Camille Desmoulins, who used it first in print on 26 July 1790. The following year, Maximilien Robespierre popularised the motto in a pamphlet about the reorganisation of the National Guard.

Note how Mantel uses Gabrielle and Marie-Madeleine to enrich our picture of Danton and the Revolution. His relatives in the country are confused about his status in Paris. “Doing nicely, son, are you?” says his father-in-law. This gives us the impression of the disconnect between revolutionary Paris and the provinces. And yet, even though Danton is ruling over the most radical club in the city, Gabrielle observed that her husband has very little in common with the "quite rough-looking types” who turn up at the Cordeliers:

The president’s desk was a joiner’s bench that happened to be lying about when they moved in. Georges really wouldn’t have much to say to a joiner, if it weren’t for the present upheavals.

In so many of her characters, Mantel understands an articulation of posture and convictions, performance and principles, which is typical of most public individuals. Her vision is never flatly cynical nor romantic. Hers is a novelist’s eye: clear and penetrating.

‘Give me four or five years, Gabrielle, and I’ll come back here and farm. We’ll get out of Paris for good. Would you like that?’

4. The Fête de la Fédération

When it came to the anniversary of the taking of the Bastille, every town in France sent delegations to Paris. A great amphitheatre was built on the Champs-de-Mars, and an alter was set up which they called the Alter of the Fatherland.

This is the high-water mark for Lafayette, “hero of two worlds,” the would-be unifier of a divided nation. It was during preparations for this festival that people began to sing "Ah! ça ira, ça ira, ça ira", the song we discussed last week (although without any lyrics about killing aristocrats).

“Ah! It'll be fine, it'll be fine, it'll be fine.” Lafayette must have hoped so.

During the ceremony, King Louis XVI swore the oath:

I, King of the French, swear to use the power given to me by the constitutional act of the State, to maintain the Constitution as decreed by the National Assembly and accepted by myself.

No longer King of France, but “King of the French”, he was accepting his role as a citizen king, his authority not descending from God but flowing upward from his subjects. As Thomas Cromwell said in Bring Up the Bodies:

‘Flow upwards? There seems a difficulty there.’

And there is, because neither king nor subjects will be content with this arrangement for long.

5. The Public Executioner

Strange – you don’t think of executioners having recourse to law, in the normal way, you don’t think of them having any animosity to spare.

Charles-Henri Sanson (1739–1806) was the royal executioner of France during the reign of King Louis XVI, and continued his profession into the bloody years of the First Republic. In total, he performed 2,918 executions. These included the gruesome dismemberment of the attempted assassin Robert-François Damiens, mentioned in Week 6, as well as the execution of Louis XVI himself, and all three of this novel’s main protagonists.

Six members of the Sanson family served as executioners.

Grace Elliot, with her mysterious political connections and her mechanical, eye-flashing flirtatiousness.

6. Would you like the chaise-longue?

And that kiss, that ten-second kiss that would have ended, if Lucile had not walked in, with a locked door and some indignified gratification on the chaise-longue. She cast her eye on it, that same item of furniture, upholstered in fading blue velvet. ‘Annette,’ Claude said, ‘why are you looking so angry?’

This extraordinary passage imbues the blue chaise-longue with melancholy, anger, and sexual frustration. Objects in Mantel’s fiction have lives of their own, and this piece of furniture will follow the Desmoulins into their new married life. A few pages later, the newlywed Lucile falls asleep on it. Whenever it reappears, I’ll always think of Annette and her uncomprehending husband, “Why are you looking so angry?”

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Three, Chapter III. Lady’s Pleasure and Chapter IV. More Acts of the Apostles

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

It’s a bit rich complaining about wallpaper when one of the first violent revolutionary outbursts was directed towards a wallpaper manufacturer. Oh! But I suppose he was a serious and worthy (because male) businessman…

Did anyone else feel as if suddenly the sun had emerged from the clouds when the narrative voice morphed into Gabrielle‘s (not so much Lucile)? All of a sudden the text is straightforward and sensible, unlike the madcap, whirling, elliptical and often confusing narrative?

Both work really well, but the contrast is delicious.

I absolutely *loved* Camille's trip to see the priest with his notary in tow. My favourite passage in the book so far.