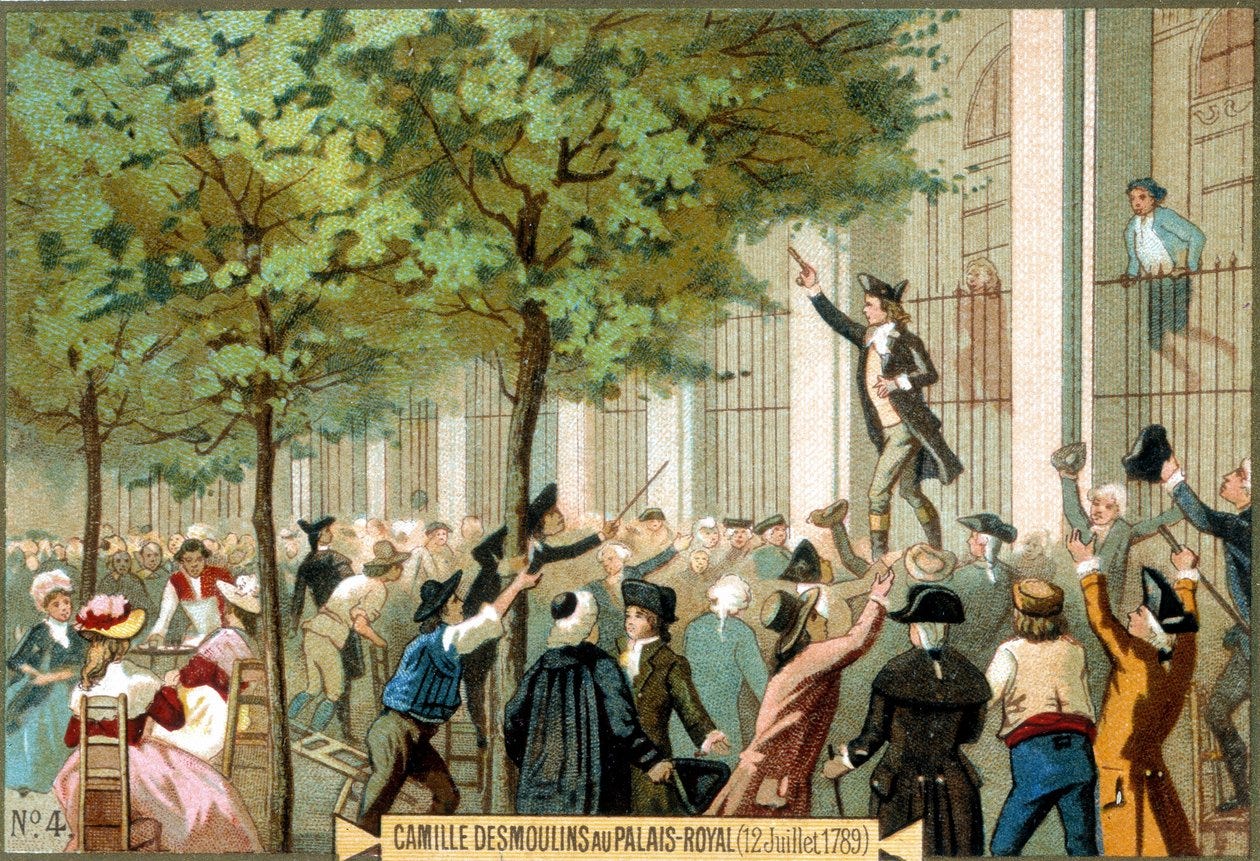

By now the crowd was hoarse and spinning with folly. He jumped down into it. A hundred hands reached for clothes and hair and skin and flesh. People were crying, cursing, making slogans. His name was in their mouths; they knew him. The noise was some horror from the Book of Revelations, hell released and all its companies scouring the streets. Although the quarter-hour has struck, no one knows this. People weep. They pick him up and carry him round the gardens on their shoulders. A voice screams that pikes are to be had, and smoke drifts among the trees. Somewhere a drum begins to beat: not deep, not resonant, but a hard, dry, ferocious note.

Last Week | Main Page | Reading Schedule | Cast of Characters | Further Resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings.

This week, we are reading Part Two, Chapter VI. Last Days of Titonville (1789).

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

It is the first week of July, 1789. Laclos goes to the Palais-Royal to recruit more firebrands to the Duke’s imminent revolution. Camille rules out the incorruptible Robespierre and recommends his indebted friend D’Anton.

11 July: Camille drops in on Robespierre in Versailles. He complains that Mirabeau is corrupting him, and they need action now under a real leader. Max declines the offer. Next day, Paris: Camille unburdens himself to D’Anton before rushing back to Versailles to see Mirabeau. The weather is hot.

Mirabeau is furious. The Queen has got Necker sacked, but there is no place for Mirabeau in the new government. Necker is popular, Camille thinks, and when news reaches Paris, there will be uproar. He returns to the city.

At the Palais-Royal, a crowd gathers. They put Camille on a chair and hand him pistols. He speaks. The mob roars. Now it has begun. The riot spreads across the city, festooned in green, then later, “Red for blood … Blue for heaven.” Blood-heaven.

In the Duplessis household, there is revolution. The women revolt against the disbelieving Claude, horrified by the news and their response to it. In the crowds, Camille sees Hérault de Séchelles with a meat cleaver, Anne Théroigne in red and blue ribbons. He seeks out D’Anton in the Cordeliers district and finds the friendly bosom of Louise Robert.

It is 14 July 1789. They have taken the Invalides. They have taken the Bastille. The army has not attacked, and everything will be quite different from now on. Camille writes to tell his father that he is famous now.

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then I recommend:

There are quite a few episodes covered next week, so if you want to get ahead of the game, listen to 12. The Great Fear and 13. The Rights of Man.

In July 1789, the weather is hot, grain is short, and bread prices skyrocket. Tempers are frayed in Paris as the capital fills up with troops, mostly foreign mercenaries.

The king’s brother, the Comte d’Artois, conspires with the queen to get Jacques Necker dismissed. Artois and fellow ultra-monarchists hate Necker for being a Protestant, foreign and a commoner. They want Louis to stand up to the increasingly radical Estates General.

Everyone interprets Necker’s dismissal as a sign that the regime is about to dissolve the Estates General and crush unrest in Paris. Fearing a massacre, crowds gather at the Palais-Royal, and Camille Desmoulins captures the mood in a speech that lays out the choice facing them: liberty or death. The city explodes.

The French Guard, sent to disperse the crowd, defects or refuses to fire. The electors of Paris attempt to take control of the rioting by recruiting a “bourgeois militia” to maintain order. The militia seizes weapons at the Hôtel des Invalides and marches on the Bastille to take its store of gunpowder.

The Bastille is stormed, the governor lynched, and its seven prisoners released.

Footnotes

1. Washington pot-au-feu

‘Anyway, there’s talk of asking Lafayette – Washington pot-au-feu, as you so aptly call him – to take charge of this citizen militia. I need hardly point out to you that this will not do at all.’

I’m curious as to the cultural significance of Camille describing the Marquis de Lafayette as “Washington pot-au-feu.” The one-pot stew is arguably the French national dish, most commonly made with beef, but with many regional variations.

Radicals like Camille suspect that Lafayette serves his own interests and lacks truly revolutionary principles. Is that why he compares him to this infinitely variable national cuisine? He is the inoffensive face of reform, to be enjoyed by rich and poor, a one-size-fits-all revolutionary.

2. Three friends on borrowed time

‘Has it ever occurred to you, Laclos, that you might be helping me to my revolution, and not vice versa? It might be like one of those novels where the characters take over the leave the author behind.’

Hilary Mantel said that one of the constraints of historical fiction is that you can’t muck around with the facts. None of her three main characters is anywhere near the Bastille on 14 July 1789. You can’t twist facts to make a better story. If you do, you’ll quickly get tangled in a muddle of your own invention.

On the eve of the revolution, Robespierre is at Versailles, biding his time. He’s not about to do anything rash:

‘No. In time, perhaps, they might respect me. But I don’t want them ever to approve of me because if they approve of me I’m finished. I want no kickbacks, no promises, no caucus and no blood on my hands. I’m not their man of destiny, I’m afraid.’

Meanwhile, D’Anton is also taking things day by day. “Dawn has broken. It’s another day. You’ve made it.” He tells Camille to stop being so “bloody horizontal” and get to where he should be rather than ending up in bed with someone. And killing time can wait:

‘Do me a favour.’ He got up and walked stiffly to the window. ‘If you’re going to commit suicide, would you leave it till about Wednesday, when my shipping case is over?’

But Camille cannot wait. The guy’s non-stop. He hurries back and forth between Paris and Versailles, hoping against hope he’ll be where it counts when the time comes. “Tomorrow is a holiday, the people can die on their own time.”

‘Maître Desmoulins feels he would like to attend a little riot. Sunday morning, Camille: why aren’t you at Mass?’

3. Bloody Jubilee

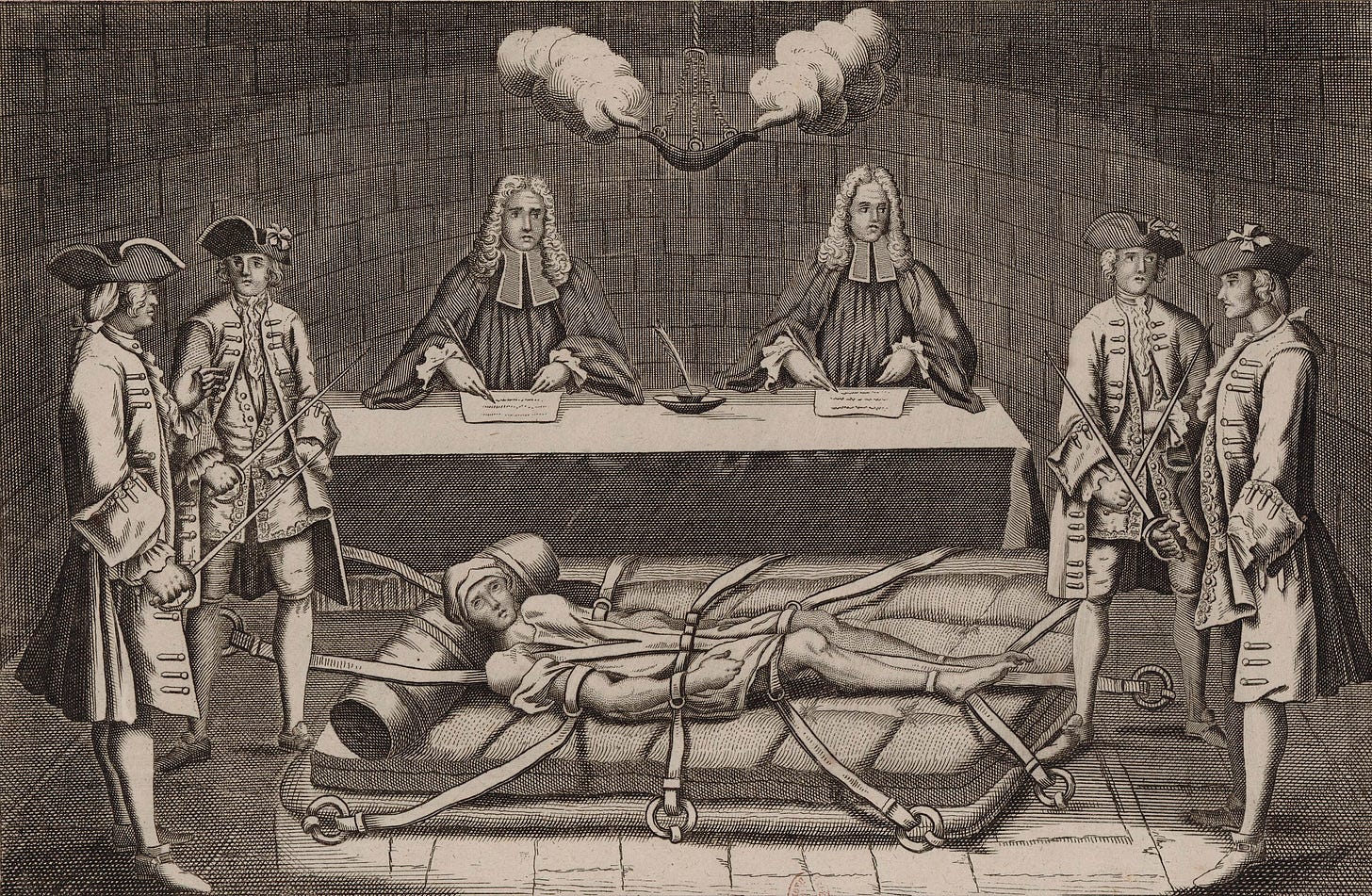

This is cruxifiction hour, as we all know. It is expedient that one man shall die for the people, and in 1757, before we were born, a man called Damiens dealt the old King a glancing blow with a pocket-knife. His execution is still talked of, a day of screaming entertainment, a fiesta of torment. Thirty-two years have passed: and now here are the executioner’s pupils, ready for some bloody jubilee.

Robert-François Damiens was the last person in France to be executed by dismemberment, drawn and quartered by horses in the Place de Grève. This was the traditional penalty for regicide, the crime Camille Desmoulins is perhaps considering at this moment.

This “fiesta of torment” became a symbol of despotic cruelty. Thomas Paine in Rights of Man explains the brutality of the French Revolution as a response to the violence of the Ancien Régime, and Joseph-Ignace Guillotin proposes the head-slicer as the enlightened alternative to this medieval practice.

‘Metaphors are good,’ he said. ‘I like metaphors. Metaphors don ́t kill people.’

(Robespierre)

4. “Now it is killing time.”

It is five past three. The exact form of the phrases does not matter now. Something is happening beneath his feet; the earth is breaking up. What does the crowd want? To roar. Its wider objectives? No coherent answer. Ask it: it roars. Who are these people? No names. The crowd just wants to grow, to embrace, to weld together, to gather in, to melt, to bay from one throat.

Camille’s “entry into history” is such a brilliant set piece in the novel. Time stands still as Desmoulins finds himself at the centre of events. His experience is exhilarating, bewildering and terrifying, and it condenses for me the sensation of reading A Place of Greater Safety. It is excessive, explosive reading. Like Camille, we are swept up by it all and carried forth.

But now he sees another beast: the mob. A mob has no soul, it has no conscience, just paws and claws and teeth.

At this moment, he recalls the opening scene of the novel, where the three-year-old Camille watches a dog chase a rat. But this time, “No one will pull him away from this spectacle. No one will chain this dog, no one will lead it home.”

Mantel combines two opposing experiences of the same event. Camille provokes the mob, but he is its victim. He is the “man of destiny” that Robespierre refused to be, but he does not feel in control of the mob or even of himself; only the mark of Mirabeau’s ring reminds him that “he inhabits the same body and owns the same flesh.”

Later, he thinks, he will write this all down in grandiose terms, “it will be a voyage into hyperbole, an odyssey of bad taste.” That will be the written record, full of heroes with well-honed speechified slogans. That is not this. This is the now, always doing and never done. This is the space into which Mantel wants to take us: history before it was history.

For a different version of this scene, watch this clip from the 1989 film La Révolution française:

5. Green for hope, red for blood

The film version above takes the historical version of Camille’s speech, in which he picks linden or chestnut leaves to be worn as a symbol of hope. Mantel’s Camille notices them while he’s up on his char, but does nothing with them… and later Mantel writes that a girl gave Camille “a bit of green ribbon” at the Palais-Royal.

It’s just another example of how Mantel decentres her characters, making them only partly authors of their own lives, and usually only after the fact.

‘Now it begins in earnest,’ Anne Théroigne said. She pulled the ribbons from her hair, and looped them into the bottonhole of his coat. Red and blue. ‘Red for blood,’ she said. ‘Blue for heaven.’ The colours of Paris: blood-heaven.

This line gives me the shivers. And the whole section lurches like a fever. We met Anne Théroigne on the stage in Week 4. And the week before that, we met the respectable Hérault de Séchelles, astonishing Danton and Desmoulins with his attention. Now Hérault is wielding a meat-cleaver. “‘It beats filing writs, doesn’t it? He had never been so happy; never, never before.”

6. The storming of the Bastille

‘The Bastille has been taken.’ He crossed the room and looked down at Camille. ‘Despite the fact that you were here, you were also there. Eye-witnesses saw you, one of the maintstays of the action.’

Like the Tennis Court Oath, the storming of the Bastille is only mentioned in passing. This is partly because none of our three protagonists were present. It is also because it will only acquire symbolic significance later when it is framed as the first act of the French Revolution. Tonight, it is just another remarkable event in these remarkable days.

At the time, the Bastille was taken to secure the ammunition held inside, and not to tear down a symbol of monarchical despotism. There weren’t even hordes of political prisoners to release – the Bastille contained seven inmates, some of whom were delinquent aristocrats put there at the expense of their families.

They did not even get to liberate the Marquis de Sade, who had been shouting revolutionary slogans from his window a fortnight earlier. De Launay’s plea to have him transferred (which opened this chapter) was heard, and de Sade was removed to the Charenton insane asylum.

When news of the chaos reached Versailles, Louis XVI asked the Duke of La Rochenfoucauld whether a revolt had taken place. “No, sire,” the duke replied. “It is not a revolt, it is a revolution.”

Watch: The Storming of the Bastille (The Rest is History)

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Three, Chapter I. Virgins (1789).

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

I'm still struggling a bit - and I'd be lost without the list of characters at the beginning. The names are as confusing as Tolstoy: the Comte? What else is he called? And the Duc! Which one is he? I'm just trying to learn to live with the confusion - but as somebody who takes being called 'a control freak' as a compliment, it's hard.

This chapter, though, definitely ups the ante. And it really captures what I've always thought: riots rarely run to plan, and nobody can really control them. Even describing a riot as a single entity may be misleading as we may be lumping together a number of individual events.

The letter at the beginning made me smile, even though I knew it was the precursor to something terrible. And the description of the killing of the governor is horrific - maybe foreshadowing the terror that is to come.

None of our leading characters - 'heroes' doesn't seem to be the right word - being there for the action is perfect. They set things off but then lose control. This will happen again, and they will lose their lives. And, of course, it's only in hindsight that we decide what is significant. (I do find it interesting that some people still talk about the storming of the Bastille as if it involved the release of lots of political prisoners - O Level history taught me differently.)

There are some great little moments sprinkled throughout the chapter. I particularly liked the description of the judge having a fine duelling pistol in one hand and a cleaver in the other. And, definitely, 'Despite the fact you were here, you were there' is spot on about how we remember what we expected to see rather than what actually happened.

Ok, now I’m in.

Before this chapter I probably would have DNF’ed on my own, but trusted in the “F&T Process.”

It is also feeling a little too familiar now, unfortunately, given the state of the world.