APOGS #5: The overthrowing of everything

Part Two, Chapter VI. Last Days of Titonville (1789)

‘What does he do?’ ‘He appears to have dedicated himself to the overthrowing of everything.’ ‘Ah, the overthrowing of everything. Lucrative business, that. Business to put your son into.’

Last Week | Main Page | Reading Schedule | Cast of Characters | Further Resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings.

This week, we are reading Part Two, Chapter VI. Last Days of Titonville (1789).

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

We have now reached 1789. Camille scuttles back to Guise to get himself elected to the Estates-General. It is a lost cause, and his father won’t help. Jean-Nicolas Desmoulins is made a deputy but is too ill to travel. Camille returns to Paris, disappointed. Meanwhile, his friend Max is on his way to Versailles…

D’Anton is too busy making money and feeding a family to play politics at the Estates-General. At the Palais-Royal, he sees that Camille has taken to standing on chairs and delivering speeches. The Duke of Orléans’ man makes a note and hires the rabble rouser from Guise.

On the morning of 24 April, Gabrielle and Georges-Jacques lose their firstborn. Out on the streets, a rumour spreads that a wallpaper manufacturer has threatened to cut wages. A mob assembles, egged on by Orléans. The army is sent, shots are fired, and men are killed. Camille is delighted, but D’Anton is grieving.

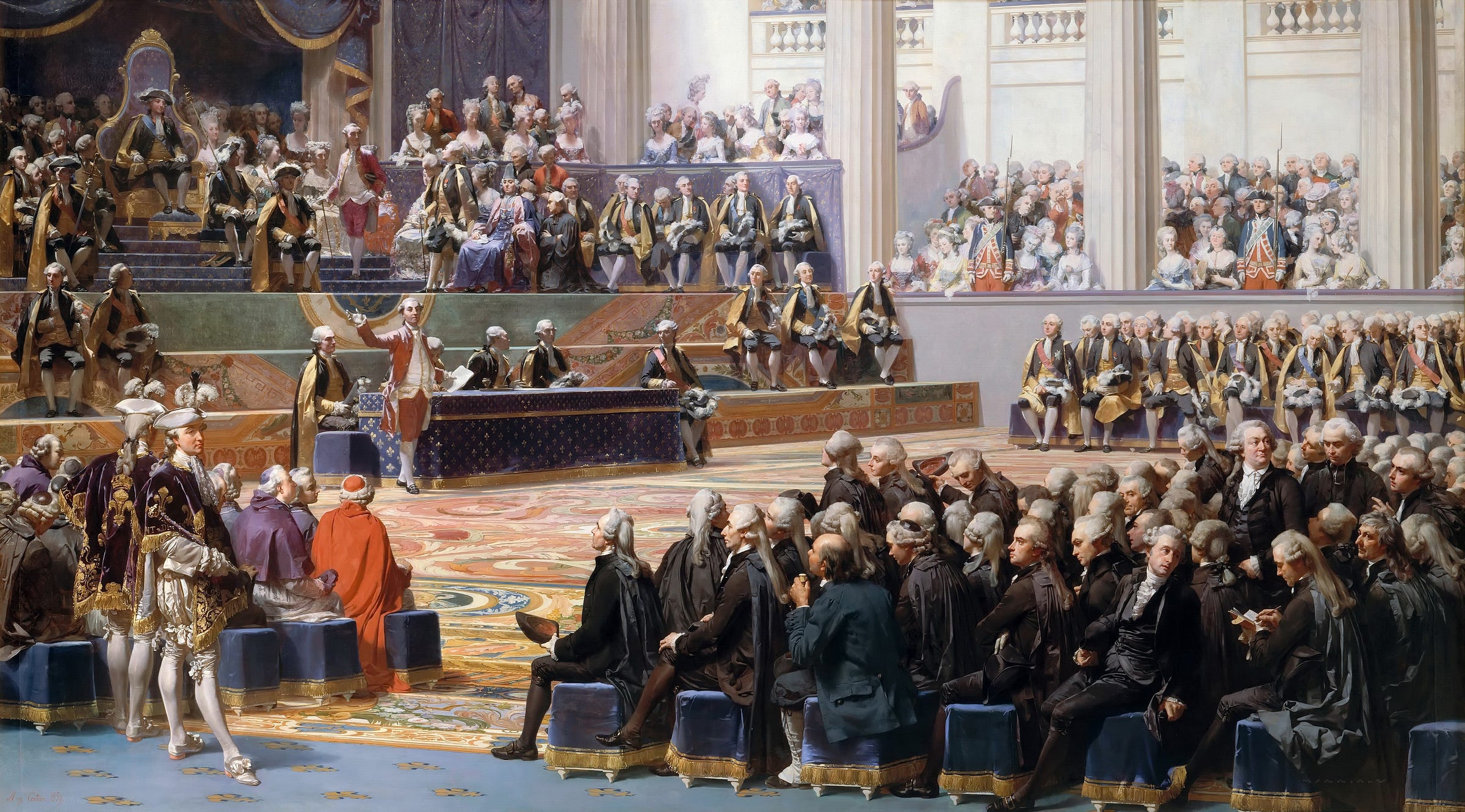

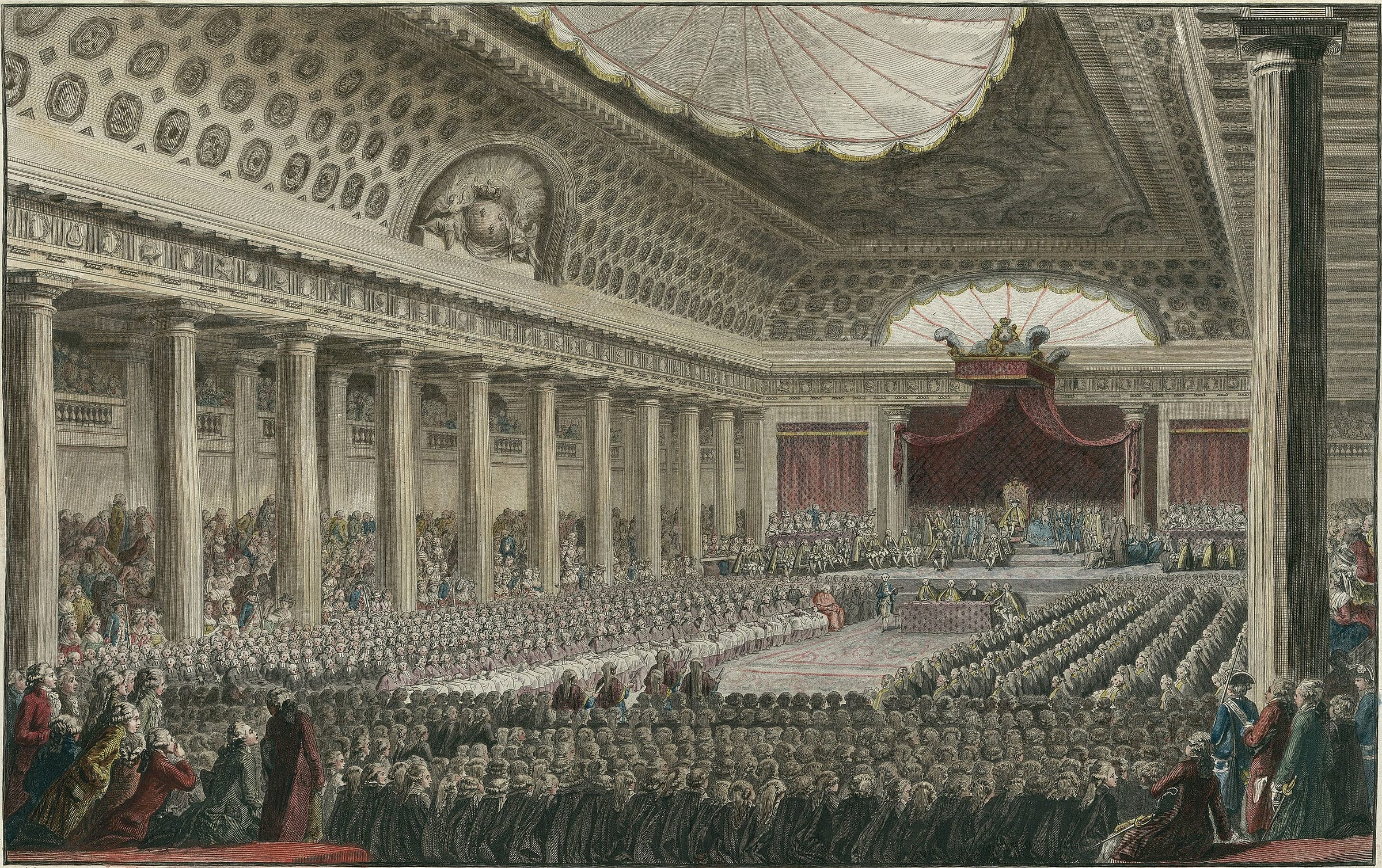

Robespierre joins his fellow deputies at Versailles as the Estates-General is convened. Camille goes to the Comte de Mirabeau for a job. After the opening session, the estates meet separately. Robespierre and Mirabeau clash over who will lead the invitation for the nobility and clergy to join the Third Estate.

In June, the priests begin to join the body, now calling itself the National Assembly. Locked out of their hall, they move down the road to the tennis court and swear an oath to give France a constitution. Three days later, the king comes and orders them to disperse. They refuse.

Back in Paris, all kinds of rumours are flying around. Picardy is in revolt; brigands are at the gates. The king is hiring German mercenaries to march on the capital. Fabre turns to his friend: “Camille. July is your promised land.”

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then I recommend listening to:

Preparations were made for the Estates-General, the first national assembly of nobles, clergy, and commons since 1614. A debate raged about what the Third Estate is and who should represent them. Elections are held, and the deputies begin to arrive at Versailles.

In April, riots broke out in the capital following rumours that the factory owner, Jean-Baptiste Réveillon, was anticipating wage cuts. The French Guard were deployed, and there were several casualties. The mood in Paris had become explosive.

At Versailles, the three estates meet separately. The Third Estate became increasingly radical, claiming to represent the people and establishing its authority to review all taxes and make a new constitution. This became the Tennis Court Oath. The king attempted to regain control, but was disregarded by the new National Assembly.

Footnotes

1. Mirabeau, demagogue

Happy Birthday, Mirabeau. Appraise the assets. He drew himself up. He was a tall man, powerful deep-chested: capacious lungs. The face was a shocker: badly pock-marked, not that it seemed to put women off.

Enter Mirabeau. A massive ego who is hell-bent on taking centre stage as the saviour of France. He’s led a colourful life, including a few years locked up in prison with the Marquis de Sade, both writing erotic works.

His scandal-ridden, profligate lifestyle has alienated his noble peers. But that’s OK because he’s got himself elected to the Estates-General, becoming the most recognisable deputy of the Third Estate.

As Robespierre says, Mirabeau has a reputation as a demagogue.1 He admits to Camille that he needs the monarchy to “assert myself through it”. When he stands up to Louis, Mantel gives him the cowardly aside: “If they come, we bugger off, quick.”

Note that Mirabeau spars with only two of our male leads. Danton is otherwise engaged in Paris. This is interesting because if Pox-marked, deep-chested, self-serving Mirabeau reminds me of anyone, he reminds me of Georges-Jacques.

Read: More on Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti, Comte de Mirabeau (Britannica)

2. We, the people

What is the Third Estate?

Everything.

What has it been, until now?

Nothing.

What does it want?

To become something

Meanwhile, Louis XVI’s Swiss wonderkid, Jacques Necker, has invited a national conversation about what constitutes the Third Estate. One answer came from the abbé Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès.

In “What is the Third Estate?” Sieyès argued that the Third Estate constituted the nation and proposed the abolition of the other two estates. It turned a national crisis into a revolutionary moment, giving the deputies at Versailles a radical agenda to overthrow the entire system of government.

300,000 copies of “What is the Third Estate?” were printed, reaching a total of one million readers. It was a manifesto for revolution.

Read: What is the Third Estate? in full

3. A lot of hot air

Only one part of M. Réveillon’s programme caught the public attention – his proposal to cut wages. Saint-Antoine came out on the streets.

Hilary Mantel captures the chaotic manner in which rumour and misinformation snowball out of control. The first victim of mob violence in the capital is a fairly progressive but patrician wallpaper manufacturer called Jean-Baptiste Réveillon.

Réveillon has secured royal privileges and protection from the Parisian guilds to produce his innovative new luxury commodity. He’s communicated with Benjamin Franklin about exporting this stuff to America. It’s the next big thing.

He collaborated with the Montgolfier brothers to make one of the first hot air balloons. The Aérostat Réveillon was sky blue and decorated with fleurs-de-lis, signs of the zodiac, and blazing suns – an aerial advertisement for Réveillon’s designs.

On 19 September 1783, the balloon carried its first living passengers: a sheep named Montauciel ("Climb-to-the-sky"), a duck, and a rooster. Everyone survived, so later that year, Étienne Montgolfier became the first human to ascend into the air in a second balloon, also made in collaboration with Réveillon.

4. The Patriotic Society of the Palais-Royal

D’Anton looked around. He was surprised at how many of them he did know. ‘This is where the Patriotic Society of the Palais-Royal holds its meetings.’

‘Who may they be?’

‘The usual bunch of time -wasters.’

The Third Estate comprises conservative, moderate, and radical factions. The most radical delegation at Versailles arrived from Brittany, which the commoners had ignored attempts by the Breton nobility to control elections and had set off alone to Paris. These deputies had no intention of working with the aristocracy.

In the capital, they formed the Breton Club with like-minded revolutionaries. Our pal Max is gently tapped for the club in this chapter: “Conference on tactics, tonight, my rooms, eight o’clock, all right?”

Within the Breton Club are the radicals who will later become the Jacobins. And there are constitutional monarchists, led by figures such as Jean Sylvain Bailly, the mayor of Paris, and the Marquis de Lafayette. These moderates meet as the Patriotic Society of the Palais-Royal.

5. The best day of my life

Yesterday was, for me, one of the best days of my life.

6. Antoine Barnave

People called him Tiger – gentle mockery, Camille now saw, of a plain, pleasant, snub-nosed young lawyer.

At Versailles, Camille bumped into the Grenoble deputy and pamphleteer Antoine Barnave. Alongside Mirabeau, he’s an influential orator in the early stages of the revolution.

‘I’m Barnave, you might have heard of me.’

‘Everyone has heard of you.’

The enormous cast of revolutionaries can be daunting and overwhelming for the reader, but I enjoy its effect: Mantel sets the scene of a crowded stage of characters, “jockeying for advantage”. We experience the revolution through the eyes of Camille or Max, relative unknowns who walk into a story already populated with egos and brimming with ambition.

Read: Biography of Antoine Barnave (Britannica)

7. Free France

‘There is a handwritten text circulating, called “La France Libre”. Is it yours?’

‘Yes. You did not think that anodyne tract you have there was the whole of my output?’

Thousands of pamphlets were published in the spring and summer of 1789. “What is the Third Estate?” was extremely successful, and “La France Libre” made similar arguments and demands. Mirabeau sees it in handwritten form because Camille still can’t get Momoro to agree to print it.

‘The answer’s the same, Camille,’ said Momoro the printer. ‘I publish this, and we both land in the Bastille. There’s no point in revising it, is there, if every version gets worse?’

8. The Hall of the Lesser Pleasures

THE HALL of the Lesser Pleasures, it was called. Until now it had been used for storing scenery for palace theatricals. These two facts occasioned comment.

Hilary Mantel describes Maximilien Robespierre’s maiden speech at the National Assembly. We feel his terror:

His heart seemed to have jumped up and hardened into his throat, the exact size of the piece of black bread the archbishop held in his hand. He turned, saw below him hundreds of white, blank, upturned faces, and heard his voice in the sudden hush, blistering and coherent:

It is an attack on the hypocrisy of the church, living in opulence while the poor starve: “Go and tell your colleagues that if they are so impatient to assist the suffering poor, they had better come hither and join the friends of the people.”

Here everything begins: 1789, 6 June, three p.m.

This public speech is juxtaposed by Lucile’s private thoughts on the same day: “Must we crawl forever?”

Robespierre’s speech was met by stunned silence, no applause and then a murmur of confusion. One deputy is recorded as saying:

‘This young man has not yet practised, he is too wordy, and does not know when to stop; but he has a store of eloquence and bitterness which will not leave him the crowd.’

9. The Tennis Court Oath

At the tennis court they stand President Bailly on a table. They swear an oath, not to separate until they have given France a constitution. Overcome by emotion, the scientist assumes an antique pose. It is, altogether, a Roman moment.

Something I really like about this book is how Mantel sidelines some quite big set pieces of the French Revolution. The Tennis Court Oath is a big deal in the mythology of the revolutionaries: when the Third Estate went from being “Nothing” to “Something”.

David’s painting captures this historical “Roman moment”. In contrast, Mantel breezes through it in a paragraph because time does not stand still, and rarely in the moment do we know we’re making history. In fact, for Max, it is his maiden speech that matters. “Here everything begins.”

What we do notice is the name of the man who suggests the location for the oath: the Parisian deputy Joseph-Ignace Guillotin. Dr Guillotin was a physician with a particular interest in reforming capital punishment.

Like Robespierre, he will be an outspoken opponent of the death penalty. After failing to abolish capital punishment, he will campaign for its democratisation by means of a “mechanism” that “beheads painlessly."

And the rest is history.

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Two, Chapter VII. Killing Time (1789).

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

A leader who makes use of popular prejudices and false claims, and promises in order to gain power

I'm sticking with this on the basis that confusion is a feature not a bug. I'm basically immersing myself in it and not attempting to try and understand the big picture.

And, in this section, confusion is what Mantel is dealing with. Meetings behind closed doors and not really knowing who is supporting whom - how unlike 21st Century politics...

The conversation between Robespierre and Mirabeau was interesting for me as it was the first time we see naked ambition coming to the fore - do they want the power to bring about revolution or do they want the revolution to bring them to power? It's hard to tell.

Something that made me smile: "Strategy, he means". Having worked in policy, there are always debates about the difference between strategy, policy and tactics (and lots of other terms). It's good to see it reflected in the 18th Century. I can't help thinking that in the modern day, our 'heroes' would all be SpAds.

Thanks, Simon. Still confused, but also sticking with it 🥰 What caught my eye this week was Mantel’s descriptions, eg “The ladies of the court were stacked on benches like crockery on a shelf …” and “When the Comte took the floor, disapproval rustled like autumn leaves.”