APOGS #4: Five years from now

Part Two, Chapter V. A New Profession (1788)

‘Listen to me,’ Camille said. ‘Five years from now there will be none of this. There will be no Treasury officials, no aristocrats, people will be able to marry who they want, there will be no monarchy, no Parlements, and you won’t be able to tell me what I can’t do.’

He had never in his life spoken to anyone like this. It was quite releasing, he thought. I might become a thug for a career.

Last Week | Main Page | Reading Schedule | Cast of Characters | Further Resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings.

This week, we are reading Part Two, Chapter V. A New Profession (1788).

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

It is now 1788. “Nothing changes. Nothing new.” And yet we are “one year to the cataclysm.”

Max in Arras, at war with the local judiciary. He is duelling in his head and putting his affairs in order. When the king calls the Estates-General, Max prepares himself to be elected.

Meanwhile, “we are all very proud of Georges.” Danton is a King’s Councillor, and Gabrielle is pregnant. Camille returns home. His Godard uncle has written a letter to Camille’s father, breaking off the engagement with Rose-Fleur, and accusing Camille of depraved behaviour in the capital.

Back in Paris, Camille visits Danton and has a run-in with one of his dogbodies: Billaud-Varenne. At the theatre, Camille meets one of Fabre’s actors, a woman called Anne Theroigne. At the Rue Condé, he checks in to see whether Claude is dead yet.

The Dantons have a son and have moved into the rue des Cordeliers. “I feel at home here,” Georges says. There’s a woman upstairs with a daughter, Louise Gély. Stanislas Freron thinks Gabrielle should start a salon. There are always people coming and going.

One of those people is Lucile Duplesis. She comes to make an ally of Gabrielle, who tries to warn her about Camille. But here is Camille to complicate things. It is always complicated with Camille.

The king calls the Estates-General. Necker is brought back, and Danton is offered a job in government. To the horror of his wife and inlaws, he turns it down. Camille says his friend has greater ambitions.

Restrictions are lifted on censorship. The Duke of Orleans begins to headhunt dangerous men who will write dangerous ideas for the people of Paris. Camille decides to give prose a try, and begins to write pamphlets.

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then I recommend listening to:

The stalemate between the parlements and the king continues into the summer of 1788. In June, rioting breaks out in Grenoble after the king attempts to suppress a regional meeting of the Estates.

On 5 July 1788, Louis XVI’s finance minister, Brienne, gives in to demands and announces the Estates General will be called. The king sets the date of 1 May 1789. Brienne resigned and the popular economist Jacques Necker is brought back into government.

There is widespread optimism that Necker has all the answers. Censorship is relaxed as a debate begins over the composition of the Estates General. The demand grows for the Third Estate to be equal in number to the nobility and clergy, and for a vote by head so that the First and Second Estates cannot outvote the Third Estate:

"Double the third, vote by head!"

Footnotes

1. You can’t paint Camille

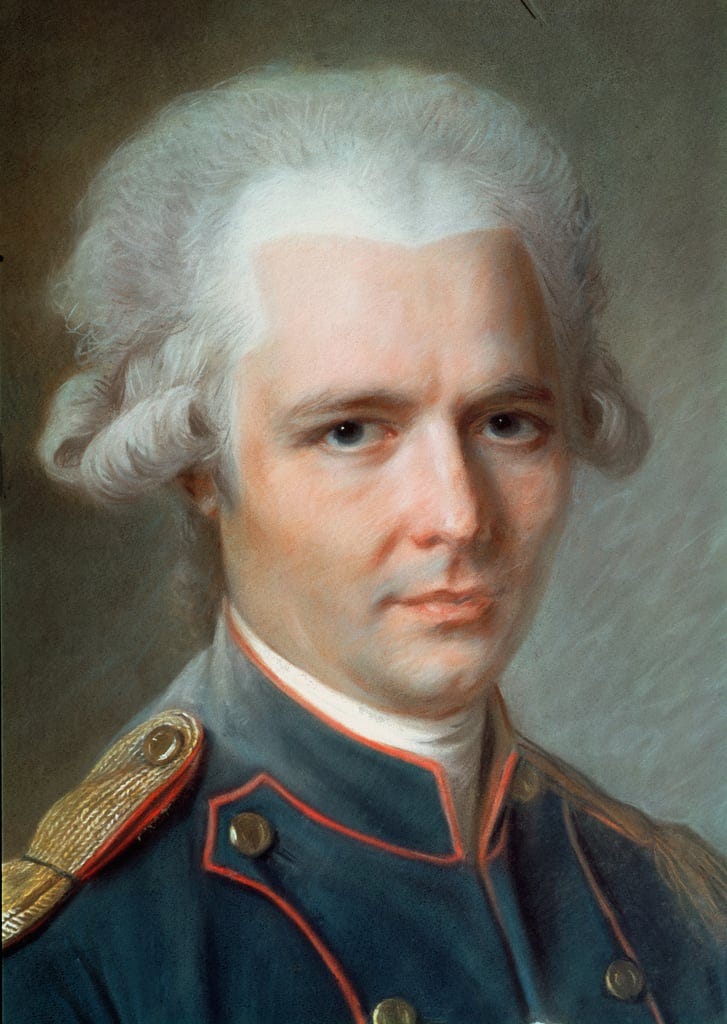

Camille’s not easy to put on paper; it’s easier to draw the men the taste of the age admires, florid fleshy men with their conscious poise and newly barbered heads. Camille moves too quickly for even a lightning sketch; she knows he is moving on, out of their lives, and she wants if she can to make things right for him before he goes.

Does anyone know who Camille’s mistress is at the start of this chapter? Her mother “painted portraits," and she is “thinking of going into her mother’s line of work.”

Mantel makes a couple of references to the difficulty of capturing Camille on paper. It feels like a knowing nod to her craft and her challenge. Later, Stanislas Fréron says Louise Robert would put Camille in a novel,

‘but she fears that as a character in fiction Camille would not be believed.’

In Bring Up the Bodies, Cromwell’s jester Anthony complains that his master is impossible to impersonate: “A plank has more expression.” Cromwell says:

‘I’ll give you a good character, if you want a new master.’

It is as though Mantel set herself two challenges at either end of a spectrum: Camille is too mercurial to be believed, and Cromwell's expression is too guarded to be read.

During the revolution, Joseph Boze will paint the electrifying portrait of Camille included above. Boze had previously painted Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. Now a Jacobin, he painted Marat and Robespierre, and only narrowly made it through the Reign of Terror with his head attached.

2. Due diligence

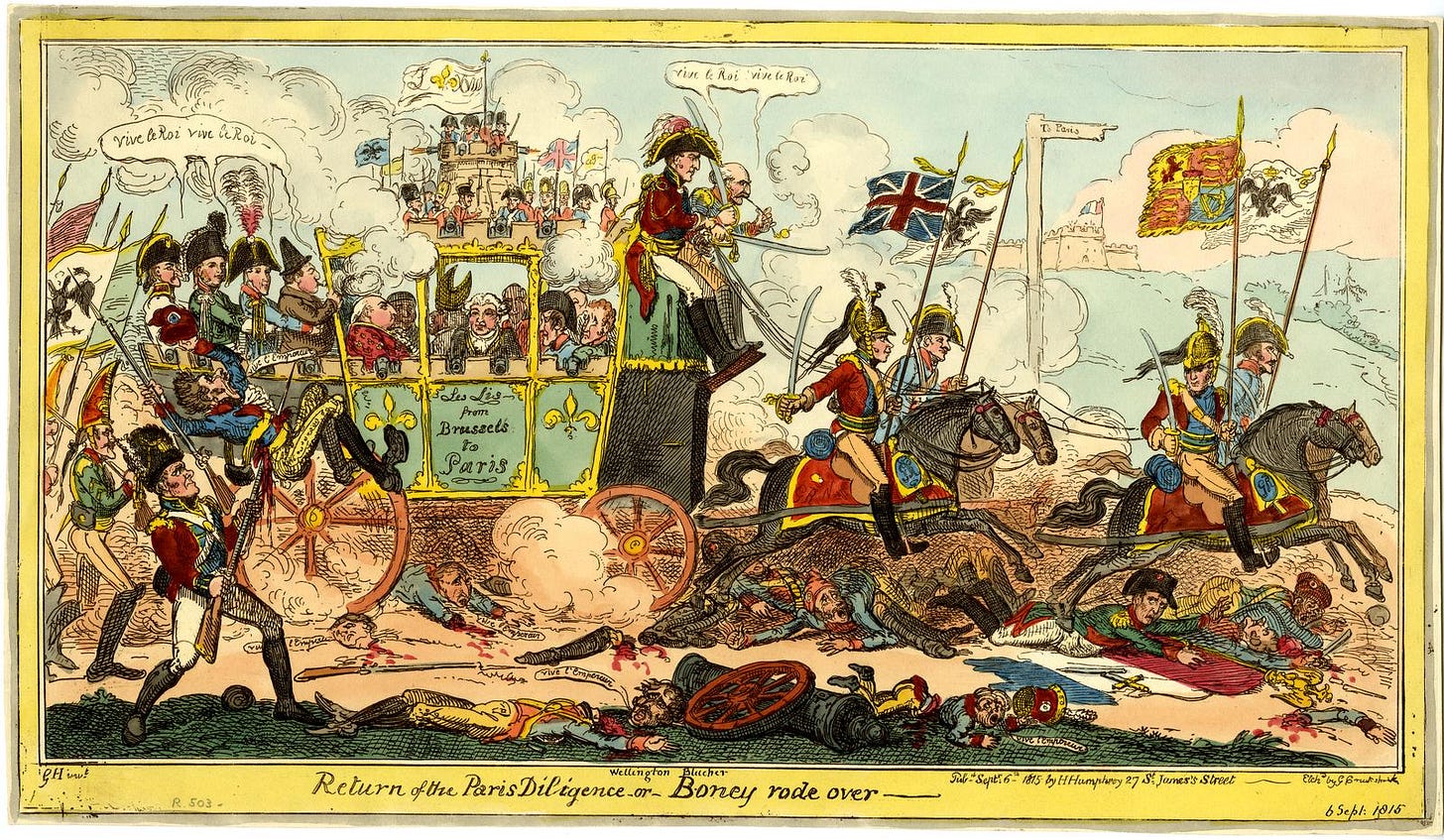

So now the diligence, not worth the name, rumbled towards Guise over roads rutted and flooded by January rains.

These huge stagecoaches were the main public conveyance of the eighteenth century for travelling long distances with plenty of luggage. They look like unruly giant bugs, a proto-omnibus, creaking our little souls inch by inch into our future.

3. The Devil’s Brood

Clément said, ‘Perhaps you will be like that diabolic Angevin who vanished at the consecration in a puff of smoke?’

‘It would be an event,’ Anne-Clothilde said. ‘Our social calendar has been so dull.’

Camille’s younger brother is alluding to the legend of Melusine, the water spirit of medieval folklore who married a Count of Anjou but turned to smoke when forced to attend Mass. The Angevin kings of England and the House of Plantagenet claimed descent from Melusine’s children. The Devil’s Brood.

This “Occult History of Britain” is alluded to by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey in Wolf Hall in his belief that Henry VIII is “one part hidden serpent.”

Read: The Tale of Mélusine (British Library)

Read: Devils in the detail (Time Literary Supplement; paywall)

Read: “From the Devil they sprang and from the Devil they shall go.”

4. The King’s Councillor

Danton is doing rather well for himself. Remember that he bought his legal office (“avocat au Conseil du Roi”) from his ex-mistress’ husband with the dowry from his marriage to Gabrielle. Mantel gives him the rather ironical and grandiose title of King’s Councillor. He’s not exactly Cromwell. This is just a legal position that allows him to put cases before the king’s council.

But there is a stark contrast between him and his revolutionary friends in Paris. As Mantel writes in “On Danton”,

Before the revolution, Danton was doing well; he was not one of the people with nothing to lose. He had a wife, a comfortable home, and an established legal practice; many of the men who were his future comrades had nothing but sheaves of unpublished poems, unsung operas and unapplauded plays.

She goes on to say, if Danton spoke of revolution, he didn’t expect it to be widespread. As we noticed last week, he adopted the “participle of nobility, calling himself d’Anton”.

Read: He Roared by Hilary Mantel (London Review of Books)

5. Trading quotations

‘“Paris is worth a Mass,”’ d’Anton said.

Camille accuses the King Councillor of hypocrisy, swearing loyalty to the Church to get his respectable job. D’Anton quotes Henry IV, who converted to Catholicism to become King of France. In week 1, we saw how Louis XVI wished to emulate “Good King Henry” and bring a divided nation together.

In the office with Camille and Danton is Jacques-Nicolas Billaud-Varenne. He’s got a revolutionary career ahead of him, and Camille can’t stand him. Billaud says:

‘As we’re quoting I’ll quote for you – “I should like to see, and this will be the last and more ardent of my desires, I should like to see the last king strangled with the guts of the last priest.”

That’s Denis Diderot, the Enlightenment philosopher and editor of the Encyclopédie. He died in 1784, his ardent desires unfulfilled. If he had lived another ten years, he would have seen such things come to pass.

Read: Denis Diderot (Britannica)

6. The collaborators

‘I think I should like to collaborate on a violent and bloody revolution. Something that would give offence to my father.’

In Danton’s offices, at the Théâtre des Variétés, on the rue de Cordeliers, the ragtag revolutionaries are beginning to assemble. In the theatre box office, Camille sees René Hébert in a heated exchange. Remember René later, for Fabre is very wrong:

‘Ah, René Hébert, what a fire-eater. What really irks him is that his triumphant destiny is to be in charge of the ticket returns.’

On the stage, Camille meets Anne-Josèphe Théroigne de Méricourt, a theatre singer with a big part to play in what is to come.

The Dantons have moved onto the rue de Cordeliers, and their house is full of future revolutionaries: Stanislas “Rabbit” Fréron (whom we last saw in week 1 at school at the Louis-le-Grand) and delicatessen owner François Robert. Robert has married the writer Louise, whom Max met in Arras last week. Out on the street, there is Louis Legendre, master butcher.

“I feel at home here,” says Danton. The rue de Cordeliers will be our home for the next few months.

7. Climate chaos and revolution

The wind tossed handfuls of sleet against the windows, and rattled in the chimneys and eaves. Jean-Nicholas raised his eyes apprehensively. ‘We lost slates in November. What’s happening to the weather? It never used to be like this.’

Around 1870, temperatures in the northern Atlantic began to plummet. Freezing winters were compounded by the eruption of the Laki volcanic fissure in Iceland in 1783, spewing 120 million tons of sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere. Harsh winters were followed by scorching summers. Crops failed, bread prices soared.

ON 13 JULY there were hail-storms; to say this is to give no idea of how – as if God’s contempt had frozen.

What a phrase. The huge hailstones killed livestock and destroyed crops, and couldn’t help but contribute to the disgruntled state of the nation:

Billaud looked up. ‘I’ve no complaints,’ he said.

‘Aren’t you lucky? You must be the only man in France with no complaints. Why is he lying?’

8. Dear diary

France was bankrupt. His Majesty continued to hunt, and if he did not kill he recorded the fact in his diary: Rien, rien, rien. Brienne was dismissed.

King Louis XVI’s diary is famous for what it omits. A year from now, the Bastille will fall and Louis will have a bad day’s hunting. Rien. However, this did not mean Louis was unaware or unconcerned about events in his kingdom. It was a record of hunting, not a document of his thoughts. But still.

Between 1774 and 1787, Louis recorded killing 189,251 animals.

9. Dangerous associations

Laclos surveyed this situation, brought his cold intelligence to bear. He began to know writers who were known to the police. He made discreet inquiries among Frenchmen living abroad as to the reasons for their exile. He got himself a big map of Paris and marked with blue circles points that could be fortified.

The balding Duke of Orléans has hired the bestselling writer, Pierre Choderlos de Laclos. His novel Les Liaisons dangereuses was discussed by mother and daughter Duplessis in week 2. Now he is the fixer for the duke, taking full advantage of the loosening grip of royal censors on the printing presses of Paris.

Camille’s first pamphlet lies on the table, neat inside its paper cover. His second, in manuscript, lies beside it. The printers won’t touch it yet, not yet; we will have to wait until the situation takes a turn for the worse.

We won’t have to wait long.

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Two, Chapter VI. Last Days of Titonville (1789).

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

A couple of people I know didn't get on with APOGS and I think I can see why. I'm finding it a bit tricky to follow - and I definitely need to keep referring to the cast of characters at the beginning.

Lots of characters turn up, but are they just background? Or maybe minor characters or even major characters we're meeting for the first time?

When Claude turned up at the Cafe du Foy, I was a bit confused. What was he doing there? Why is he so cordial? It feels a bit disorientating.

And I don't have a clue who Camille's mistress is - nor her mother. (I also don't have a clue where Camille gets all his energy from.)

I'm still enjoying it but I'm now trying to read it in terms of a series of snapshots rather than a single picture. Maybe I will be able to make sense of it at the end - perhaps it's a literary form of pointillism.

Ok, this book officially has its hooks in my brain now! Knowing very little about the details of the French Revolution, and trying to balance not spoiling the plot with having at least some necessary background to understand the nuance has been a tricky juggling act so far (and utterly impossible without all your excellent info and character summaries, Simon!). Now we're almost a month in I thought I'd go back and re-read weeks 1-3, and I found it so rich and rewarding to see our key players' childhoods the second time around, knowing a little more about where they might be headed. They're definitely taking shape in my mind, and thanks to the Revolutions podcast, the broader picture is coming clear. The tension mounts indeed!