APOGS #15: For the public safety

Part Five, Chapter IV. Blackmail & Chapter V. A Martyr, a King, a Child & Chapter VI. A Secret History

'It's a measure we have to take.' 'For the public safety,' Lucile said. This was an expression that was coming up in the world; for the last few weeks it had been on everyone's lips. 'The public safety. But somehow, whatever measures are taken, one never feels any safer. I wonder why that is?'

last week | main page | reading schedule | cast of characters | further resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings. And for the full experience, read online.

This week, we are reading Part Five, Chapter IV. Blackmail & Chapter V. A Martyr, a King, a Child & Chapter VI. A Secret History.

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

On 14 January, Danton is recalled to Paris to vote for the death of Louis Capet. He is greeted by a blackmail letter from one of the king’s ex-ministers, alleging that Danton has taken British money. We have, you know.

The blackmailer wants Danton to save Louis and says a copy of this letter has been sent to the president of the Convention. Danton looks finished. He hits Gabrielle and insults Camille, before securing the letter from Defermon. He burns it before Camille can read what it says.

20 January, 1793: Michel Lepelletier becomes the first martyr of the Revolution for voting for the king’s death. Louis is executed the following morning by guillotine. In February, Danton’s upstairs neighbour, Louise Gély, entertains the Jacobins and her suitor Claude Dupin. On 10 February, Gabrielle dies in childbirth.

Danton buries his wife, receives letters of condolence and returns to Belgium. Civil war breaks out and Danton announces a new court, the Revolutionary Tribunal. Louise Gély takes care of his children and begins to take care of Danton. In Belgium, Dumouriez loses a battle and exchanges threats with Georges-Jacques. It is March, 1793.

Back in Paris, Louise Gély hides Danton until he is ready to get drunk with Camille and face the committees and the Convention. He tells Camille he is infatuated with Louise. He tells the Convention that Dumouriez is a traitor. When Dumouriez abandons his post, he takes Philippe Égalité’s son with him. Robespierre demands that the Orléans family and the Brissotins be brought before the new Tribunal. But as deputies they are immune from prosecution.

Marat makes a modest proposal. The Convention agree to lift its immunity from prosecution. Everyone looks shifty and carnivorous. Camille goes home to write his pamphlet: A Secret History of the Revolution. Roland, Brissot and the rest have conspired against the French Repbulic. Their day of judgement has arrived.

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then I recommend listening to:

Second half of 26. The Trial of Louis XVI

Episodes 27 and 28 deal with events in the war and the provinces. These events are not dealt with in detail in A Place of Greater Safety, which focuses on the revolutionaries in Paris.

After the insurrection of 10 August and the September massacres, the National Convention spend four months debating what to do with Citizen Louis Capet, previously the King of France. In December, he is tried for treason and other crimes, and in January, he is convicted and executed.

Meanwhile, the early military advances in Belgium are followed by defeats as the French attempt to move north into Holland. The National Convention begins to suspect that General Dumouriez is using the war as a launchpad to turn on Paris and restore the monarchy.

The execution of the king, mass conscription and new taxes fuel unrest in the provinces, especially in western France, where a major counter-revolutionary insurrection begins in the Vendée. The Parisian Jacobins begin to talk about a federalist conspiracy to undermine the central government and the revolution.

In March, the National Convention establishes the Revolutionary Tribunal for the trial of political criminals. Robespierre believes Dumouriez and Brissot are using the war to overthrow the Republic. An attempt to arrest Dumouriez fails, and the general defects to the Austrians.

Dumouriez left with Philippe Égalité’s son, Louis Philippe – the future King Louis Philippe I, after the Bourbon restoration. This puts the Orléans family under scrutiny, as the Mountain begin to identify the perceived enemies of the Republic to be brought before the Revolutionary Tribunal.

Footnotes

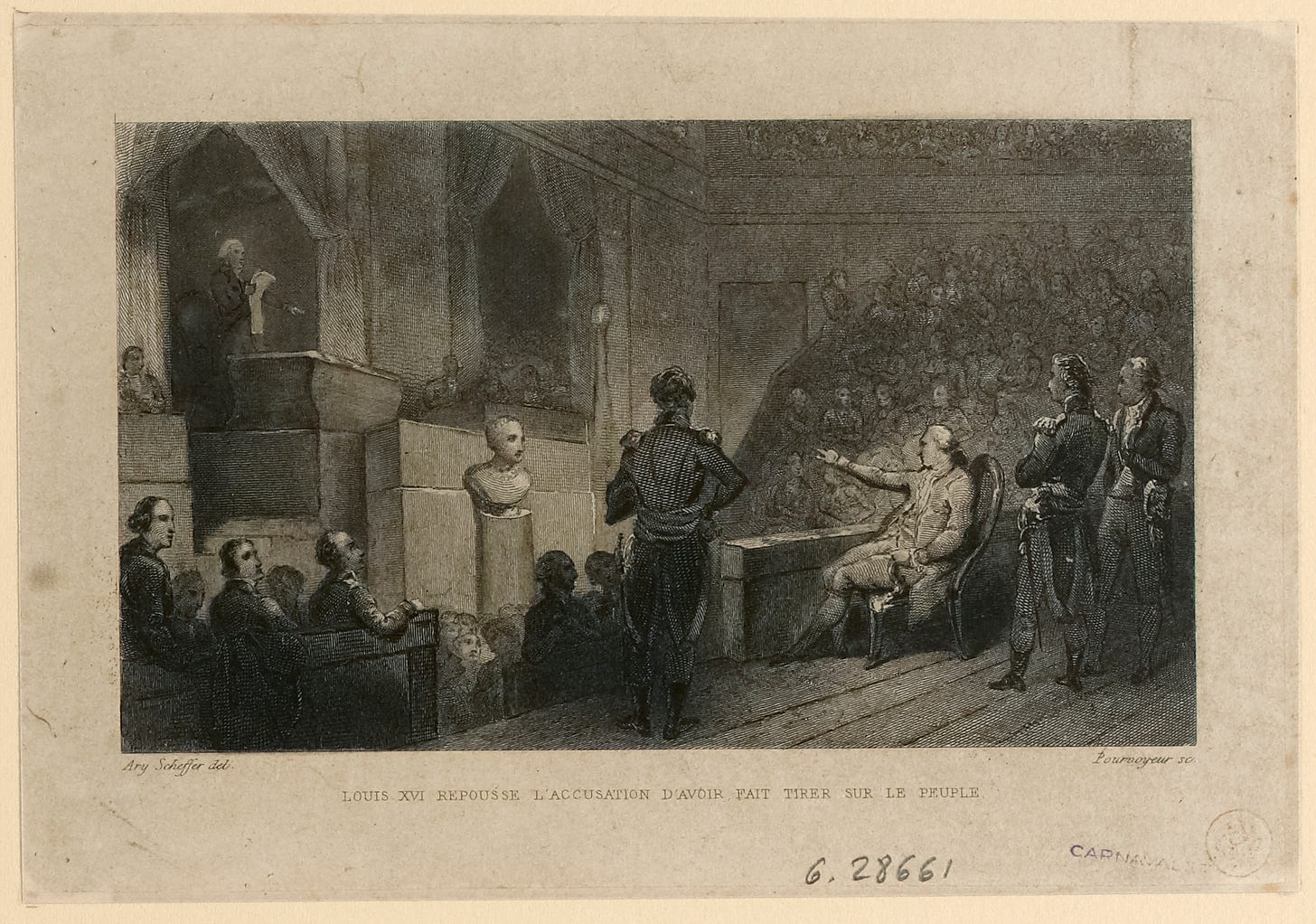

1. The trial of Louis the Last

The King’s trial is over. The city gates have been closed. One cannot reign innocently, the Convention has decided. Merely to have been born condemns Louis to die? ‘That is the logic of the situation,’ Saint-Just says calmly.

Citizen Louis Capet’s trial began on 3 December before the National Convention. Louis attended his trial twice, to hear the 33 charges made against him and make his defence. On 14 January, they began a series of votes that condemned Louis to death.

Robespierre had opposed a trial and considered it unnecessary. He now joined deputies in demanding capital punishment and preventing an attempt to ratify the decision in the provinces. Philippe Égalité voted for his cousin’s death, a move that surprised even supporters of the king’s execution.

‘What have I done to my cousin Orléans, that he should persecute me in this way?’

Trial and Execution of Louis XVI (World History Encyclopedia)

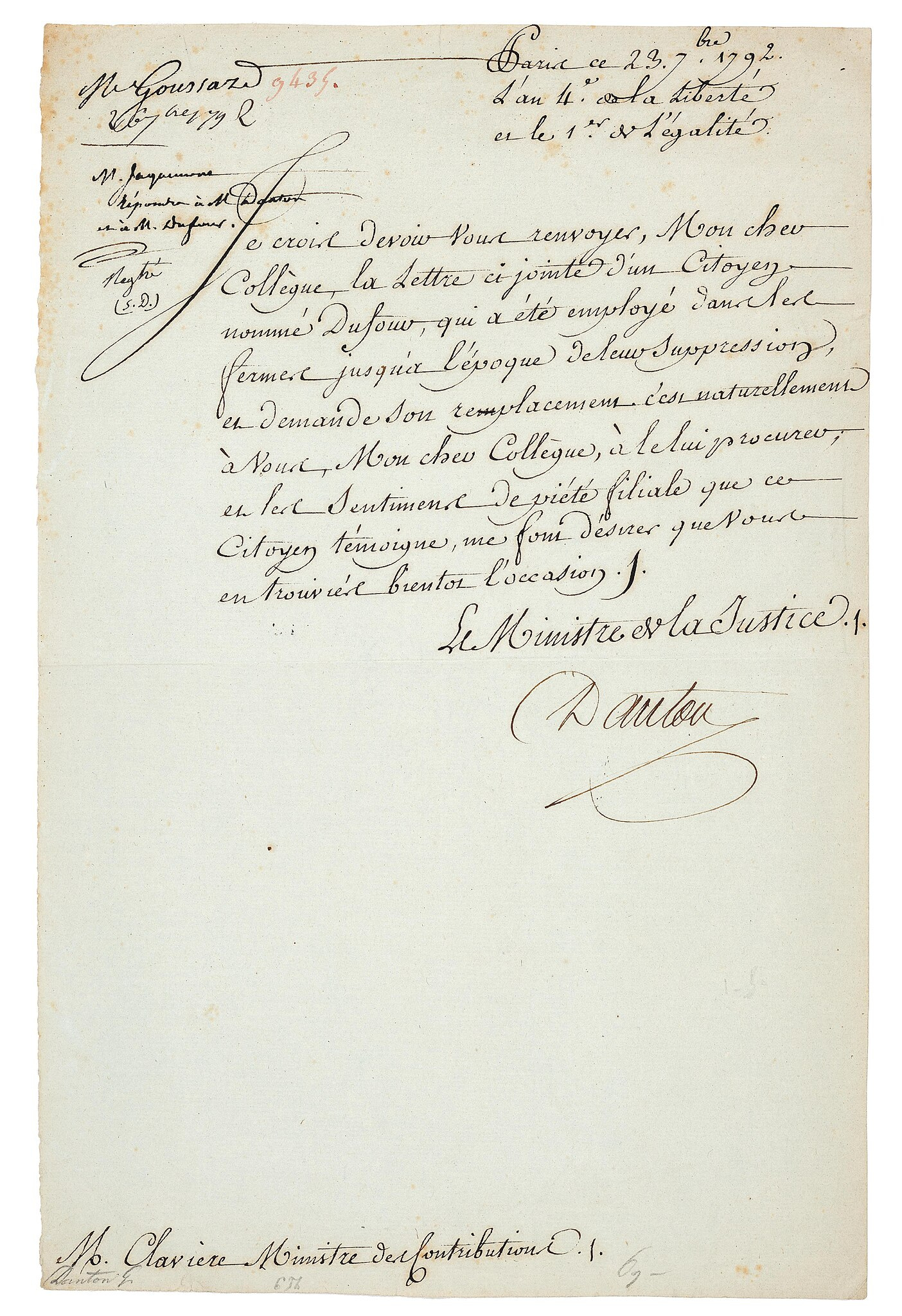

2. Blackmail

‘It is a blackmail letter, Gabrielle,’ Camille said flatly. ‘Montmorin was Louis’s Foreign Minister; we forced him out of office after the King tried to escape, but he was always in Louis’s inner circle. He was killed in prison in September. This man de Molleville was Louis’s Minister of Marine.

I don’t think there is any surviving evidence that Danton either received money from William Pitt’s government or that he was blackmailed into saving Louis Capet. But absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and Mantel is given all the creative license she needs to paint her picture of revolutionaries hemmed in on all sides.

All four characters privy to this letter will be dead within 18 months, and Danton burns the letter itself before Camille gets a chance to read it. Crucially, Robespierre knows nothing about it, which helps develop the drama as the relationships between our revolutionaries go from bad to worse.

This episode is essential. For the first time, we see Danton afraid – and we note his response: he hits Gabrielle, attacks Camille and goes off to bully worms from the swamp. It creates the condition for an exchange between his wife and Camille, where Desmoulins admits his love for Danton. And it ensures that the Dantons separate on a sour note that leads to Georges-Jacques’ remorseful depression in the next chapter.

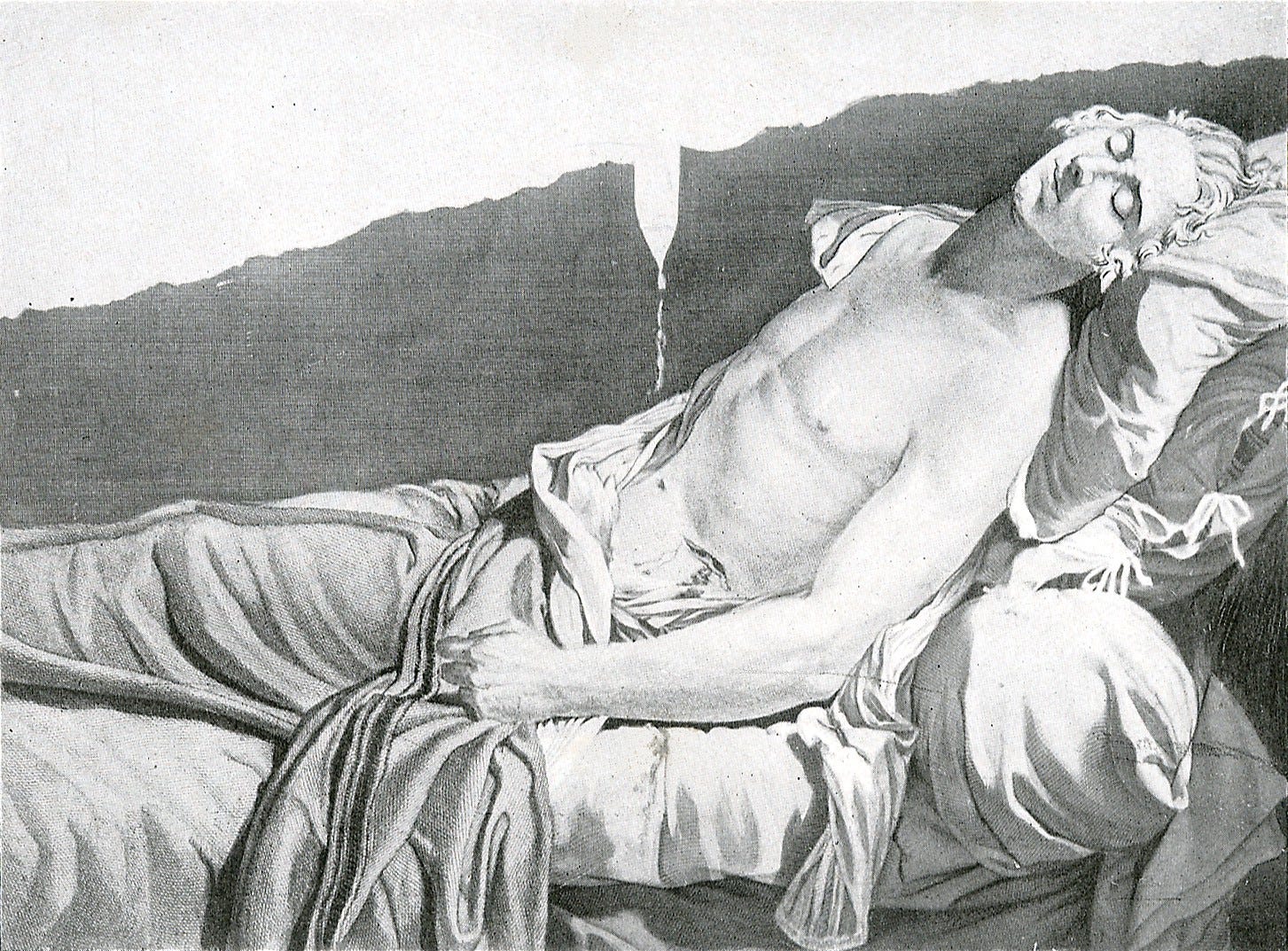

3. A martyr, his daughter, her portrait

They have sent for surgeons, the best the republic can offer; they have sent, too, for the artist David, so that he can see what a martyr looks like, so that he can watch moment by moment as death effaces the features and immortality sets them into a better mould.

The word “immortality” is working hard in this sentence. Jacques-Louis David’s The Last Moments of Michel Lepeletier hung in the National Convention alongside The Death of Marat – immortalising both as martyrs of the Revolution. But the first painting was probably destroyed by Lepelletier’s daughter later in life to erase her family’s links to the revolution.

Suzanne le Peletier was 11 when her father died. The French Republic adopted her as a “Daughter of the State”. In 1797, her uncles tried to prevent her from marrying a Dutchman and thereby forfeiting her French citizenship. They argued that the "first daughter of the republic" could not marry a foreigner – even though this meant she could not act as a full independent citizen and decide her own fate.

Nevertheless, she married Jean-François De Witt and, in 1802, enacted her revolutionary right to divorce him. Jacques-Louis David painted her portrait in 1804:

Her father had been the Marquis de Saint-Fargeau, before renouncing his title and embracing revolution. Her descendants owned the Château de Saint-Fargeau in Burgundy until the 1960s.

4. The death of Louis

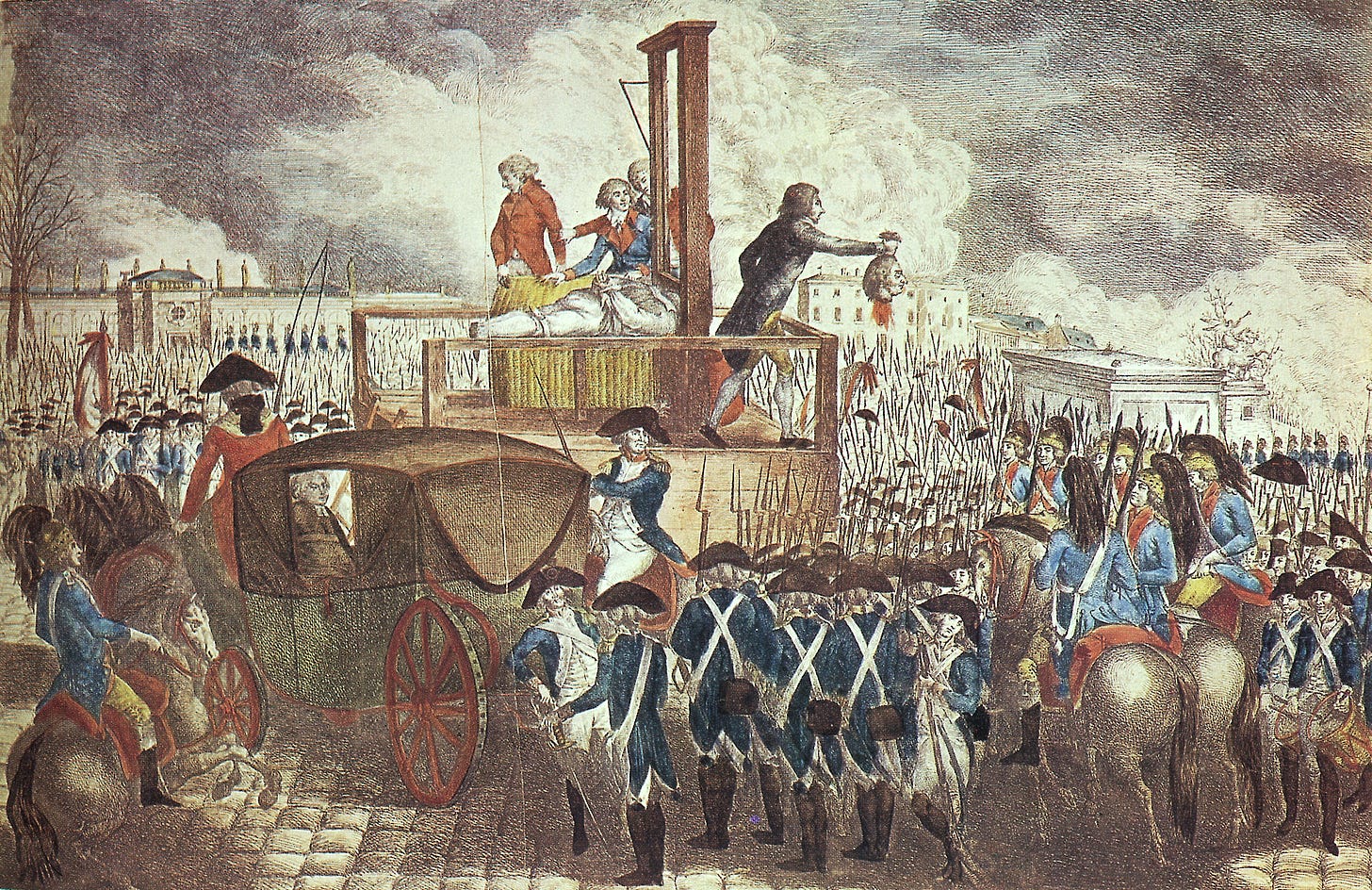

10.30 a.m. The coat is snatched away from Sanson’s assistants, and cut up into snippets. Hot pies and gingerbread are for sale in the Place de la Révolution. People are swarming around the scaffold, soaking rags in the spilled blood.

One slippery paragraph of sibilants and it is all over: the King is dead, long live the Republic! The lethal efficiency of the guillotine means that we look away for less than a second at the snacks on offer, and by the time we look back, people are already soaking up bloody momentos.

In the painting above, you can see Jacques Roux taking notes as an official witness. He wrote:

Capet was never out of our sight up till the guillotine. He arrived at 10 hours 10 minutes; it took him three minutes to get out of the carriage. He wanted to speak to the people but Santerre wouldn't allow it. His head fell. The citizens dipped their pikes and their handkerchiefs in his blood.

According to Louis’ Irish confessor, Henry Essex Edgeworth, the king said on the scaffold:

I die innocent of all the crimes laid to my charge; I Pardon those who have occasioned my death; and I pray to God that the blood you are going to shed may never be visited on France.

In London, the Observer reported that:

The short length of time in which he appeared on the scaffold, and the interval of the fatal blow, no more than two minutes elapsed! Instantly the executioner lifted his head, and, amidst the flourish of trumpets, exclaimed, “Thus dies a traitor!”

Louis was buried at the Church of the Madeleine. A witness reported:

In pursuance of an executive order, the body lying in its open coffin was thrown onto a bed of quicklime at the bottom of the pit and covered by one of earth, the whole being firmly and thoroughly tamped down. Louis XVI's head was placed at his feet.

An apocryphal story circulated after the death of Louis that an anonymous Freemason splashed the king’s blood over his crown at the execution and declared: “Jacques de Molay, thou art avenged!” You may remember we discussed the curse of Molay in week 13.

BBC Witness: Henry Edgeworth’s first-hand account of the death of King Louis.

The Rest is History podcast: The trial and execution of King Louis XVI.

5. The death of Gabrielle Danton

The maid found a handkerchief of hers, under the bed in which she had died. A ring that had been missing turned up in his own writing desk. A tradesman arrived with fabric she had ordered three weeks ago. Each day, some further evidence of a task half-finished, a scheme incomplete. He found a novel, with her place marked.

Readers of The Mirror and the Light may recognise the parallels here to Cromwell remembering his wife’s possessions and unfinished things.

Interestingly, Mantel doesn’t describe the disinterment of Gabrielle’s body, mentioned by Danton’s biographers. In David Lawday’s account, Danton was so distraught at arriving home after her burial that he took the sculptor Louis-Pierre Deseine to dig her up and make a death mask and bust of his wife:

As the lid came off and Gabrielle's waxen head showed in the flickering torchlight, Danton let out another terrible cry. With his huge fists he fumbled below the corpse and pulled his wife out, imploring her to forgive him, hugging her to him, squeezing her and kissing the stiff grey bloodless lips. With a groan he placed her tenderly on the displaced lid and motioned to the sculptor to do his work.

Given that Hilary Mantel does not shy away from the ghoulish and grotesque, it is a surprise not to find this scene in the book. Perhaps even she thought it a bit much. She’s on record as saying there are some details she left out of the Cromwell books because they seem so unlikely that they would challenge the readers’ credulity.

6. Our Lord and Saviour Danton

‘How old are you Danton?’

’Thirty-three.’

’Lord. Well, I suppose revolution is a young man’s business.’

Mantel’s wit. Blink and you’ll miss it.

7. War in the Vendée

March was near-disaster. In Holland the depleted armies crashed to defeat. In the Vendée insurrection became civil war. In Paris mobs looted shops and smashed Girondin printing presses. Hébert demanded the heads of all the ministers, all the generals.

In the Author’s Note, Mantel says that A Place of Greater Safety is not

an overview or a complete account of the Revolution. The story centres on Paris; what happens in the provinces is outside its scope, and so for the most part are military events.

So the outbreak of civil war in western France is pushed into the background. The War in the Vendée is the focus of Victor Hugo’s novel Ninety-Three. While other counter-revolutionary uprisings were suppressed, a Royalist insurrection became embedded in the Vendée and Chouannerie regions, south and north of the river Loire.

The uprising was a response to mass conscription to fight the Revolutionary War and the decapitation of Louis XVI. In the poor and staunchly Catholic Vendée, there was less hostility towards the local church and nobility, and strong opposition to Parisian radicals.

This civil war lasted three years and was responsible for some of the worst atrocities of the 1790s. Estimates of the death toll range from tens of thousands to 200,000, and it has since become a deeply symbolic and contentious episode in French history.

The Vendée uprising (Alpha History)

The War in the Vendée (Crozier On Stuff)

Threading through the solid-packed bodies, like a coffin-worm at a wedding feast, came Dr Marat.

8. The Committee of Public Safety

‘I suppose I had better get myself together. Georges-Jacques and I are being elected to a committee today.’ 'Which committee?' 'You don't really want the details, do you?'

Oh, but we do. Camille and Danton have joined the new Committee of Public Safety, in the week that Mantel notes that the expression “public safety” is “coming up in the world.” In the first few months of its existence, the committee will be known as the Danton committee. But later, Robespierre and Saint-Just will turn it into the main instrument of the Reign of Terror.

‘The public safety. But somehow, whatever measures are taken, one never feels any safer. I wonder why that is?’

We’ll be hearing much more from the committee soon.

9. A Secret History

‘Your Tribunal was a mistake,’ he said without preliminary. ‘We are entering a time of terror.’

The title of Chapter VI is taken from Camille Desmoulins’ pamphlet, “The history of the Brissotins, or, Part of the secret history of the Revolution, and of the first six months of the Republic.” A section is quoted at the end of the chapter.

It is a response to Brissot’s call for the Paris Commune and the Jacobin Club to be dissolved, and it marks the beginning of all-out war between the Mountain and the Gironde.

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Five, Chapter VII. Carnivores & Chapter VIII. Imperfect Contrition.

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

The quip about Mantel's humor reminds me of the bit in Wolf Hall:

"Mark says I look like a muderer."

"Didn't you know?"

It's one of the many things I love about Mantel's work. It's so quietly funny. I think too many historical writers forget that people in the past had a sense of humor, too.

While I bow to the talent of Mantel, I am weary of this hot-house of a novel. The “cleverness” of the author, the tangled domestic situations and the (to me) somewhat confusing political alliances are wearing me down, though, of course I will continue and finish APOGS, in part because Simon is a masterful guide. I am always eager to read his (and fellow readers’) commentary and observations each week. And I am learning about Paris during the French Revolution. Or re-learning it perhaps…

I am also currently slow-reading Anna Karenina and I’ll choose Tolstoy over Mantel any time. Tolstoy’s writing is often brilliant and even elegant at times. Mantel is sometimes brilliant but less coherent.

I always have trouble separating an author from his or her writing and sense a turbulence that makes its way onto her pages….a life that wasn’t easy perhaps, corralling a drive and an intellect that burned white hot at times.

I love these slow reads, and am always trying to explain what they are, hoping to seduce others to join.