APOGS #14: Stumbling towards death

Part Five, Chapter II. Robespierricide & Chapter III. The Visible Exercise of Power

If Camille were not here – if he were permanently not here – what would lie before her would be a sort of semi-demi-half-life, dragged out for duty, sick and cold and stumbling towards death; the important part of her would be dead already.

last week | main page | reading schedule | cast of characters | further resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings.

This week, we are reading Part Five, Chapter II. Robespierricide & Chapter III. The Visible Exercise of Power.

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

We begin with the complicated love lives of our revolutionaries. Manon Roland has fallen in love with François Buzot, but can’t stop thinking of Georges-Jacques Danton in bed with Gabrielle or Lucile Desmoulins. Fabre comes to visit, and Manon lets her husband know the score.

Meanwhile, Eléonore Duplay is busy seducing Maximilien Robespierre. She is infinitely more successful than her younger sister was with Camille. Speaking of the Lanterne Attorney, he’s at the Ministry thinking about the arrival in Paris of Antoine Saint-Just, the youngest deputy of the new National Convention.

Saint-Just and Camille are not friends, but they are allies – both sitting on the Mountain in the Convention, plotting the downfall of their enemies, the Girondists or Brissotins. The Girondists intend to lay the blame for the September massacres at Robespierre’s feet. Louvet calls it Robespierricide. Danton considers an attack on Robespierre as an attack on himself. Of course he does.

The Robespierres come to tea with the Duplays, and Charlotte Robespierre tries to extricate her brother, but Max is going nowhere. He delivers his response to the Robespierricide, justifying the massacres as an inevitable sequel to the 10 August insurrection. Camille feels queasy, fights with Saint-Just, and leaves early.

Later, Max and Camille patch up their differences, and Robespierre attempts to explain Camille to Saint-Just.

Danton leaves the Ministry and decides to go to war. Lucile is batting away men left, right, and centre: Stanislas Fréron (Rabbit), the aristocratic Hérault de Séchelles, and General Dillon. And despite appearances, Lucile is more in love with Camille than ever. Camille slouches in on Marat to design the fates of their enemies.

‘I wonder if our masters realize what assets we are? You with your sweet smile, and me with my sharp knife?’

Before Danton departs for Belgium, he talks to Max about legal process and capital punishment. He leaves a heavily pregnant Gabrielle behind, and an ally in the Convention arguing for the execution without trial of Citizen Louis Capet. Max Robespierre:

Louis must die so that the nation can live.

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then I recommend listening to:

The first half of episode 26. The Trial of Louis XVI

This week’s events play out as a spate of military victories on the front gives the revolutionaries breathing space to declare war on one another. The Girondists initially dominate proceedings at the National Convention, but face virulent opposition from Robespierre’s reformed Jacobins – now referred to as the Mountain for occupying the high tier of seats to the left of the lectern.

Previously, the Girondists and the Mountain were divided over the war. Now, they disagree with each other on everything. The Girondists accuse Robespierre of orchestrating the September massacres with Jean-Paul Marat. The Mountain oppose the Girondist plan to put Louis Capet on trial.

In the last few months of 1792, the National Convention thrashes out what to do with the ex-king. There is no legal precedent, so they have to make one. Just turned 25, Antoine Saint-Just was the youngest member of the Convention. His triumphant maiden speech called for Capet’s death, for “no one can reign innocently." Robespierre agreed. In the Tuilleries, discovered documents showed Louis’s correspondence with émigrés and his interference with elected deputies, including the hero of the revolution, the Comte de Mirabeau.

Footnotes

1. Skits and squibs

In private, though, these skits and squibs brought her near to tears; she asked herself why she was meted out the same treatment as that peculiar, wild young woman Théroigne, the same treatment – when she thought of it – as the Capet woman used to get.

Much of these two chapters is given over to the complicated love lives of the revolutionaries, played out in the newspapers and under the public eye. The respectable and intellectual Manon is horrified by it all. She has discovered that public women are not allowed a private sexuality, regardless of their republican and democratic principles.

A Doomed Romance: Manon Roland and François Buzot (warning: spoilers)

Roland and Buzot’s love letters were published long after their deaths. In this chapter, Buzot innocently asks whether she has “read Cicero?” We know from her memoirs that she was indeed “well-read” and didn’t need a man to explain the ethics of happiness and moral responsibilities.

2. Éléonore Duplay

One extruxiating sex scene later, and Mantel plumps for a version of history where Max and Éléonore Duplay consummate their relationship. You might not be surprised to know that Charlotte Robespierre denied that anything went on, and some historians agree with her. Nevertheless, (spoilers:) after his death, Éléonore wore black for the rest of her life, never married and became known as the Widow Robespierre.

3. Danton’s future

In the small hours, Camille had found him solitary in a pool of yellow candlelight, poring over the deeds of his Arcis property, each boundary stone, water course, right of way. As he lifted his head Camille had seen in his eyes a picture of mellow buildings, fields, copses and streams.

Camille calls these Danton’s “delusions”, and we have already seen him think about his life after the revolution. One development in these two chapters is Danton’s reluctant realisation that these are delusions, for we no longer expect to have “natural lifetimes.”

Mantel will perform the same trick in the Tudor trilogy, where Thomas Cromwell will think wistfully about his retirement at Launde. I must be sentimental because this writing crushes my heart, as it squeezes Cromwell’s in the Tower, listening to Francis Weston talk about his old age.

4. The Battle of Valmy

When the news of the victory at Valmy reached Paris, the city was delirious with relief and joy, and it was only later that a few people began to wonder why the French had not pursued their immediate advantage, chased up Brunswick and cut his retreat to pieces.

Valmy is less than 100km away from Danton’s birthplace in Arcis, and 100km from Paris. No one knows exactly why Brunswick unexpectedly abandoned the battlefield and handed victory to the French. The theory that he was bribed with the French crown jewels is probably far-fetched.

It seems more plausible that the Prussians were unwilling to risk their men against a reinvigorated French line singing “La Marseillaise” and “Ça Ira”, fighting for the defence of their capital. Moreover, the Russian invasion of Poland was already giving them something else to worry about.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was present at the battle, telling his defeated comrades that:

‘Here and today, a new epoch in the history of the world has begun, and you can boast you were present at its birth.’

Within days, the National Convention had abolished the monarchy and declared a new French Republic – so that the Battle of Valmy came to be seen as the first victory in the field for revolutionary France.

Battle of Valmy (World History Encyclopedia)

5. Death and the Mountain

In time defeats will occur, and betrayal, conspiracy and mere half-heartedness receive a ghastly reward; as the numbers of the Convention dwindle, one can seem to see every day on the empty benches a figure of Death, smiling, familiar and spry.

This chilling sentence cuts this surprise victory from under us. We are given a glimpse into the coming months, when even “mere half-heartedness” will be construed as treason and send you to the guillotine.

When the deputies took their seats in the Riding-School for the National Convention, no one wanted to sit on the right where the Feuillant monarchists had once sat. Those deputies of the Legislative Assembly were now considered traitors.

But there were 786 deputies and only so many seats. So with ominous foreshadowing, the Girondists reluctantly take up their place on these cursed benches.

Looking down on them from on high were the Montagnards: Danton, Robespierre, Camille Desmoulins, Antoine Saint-Just and Jean-Paul Marat.

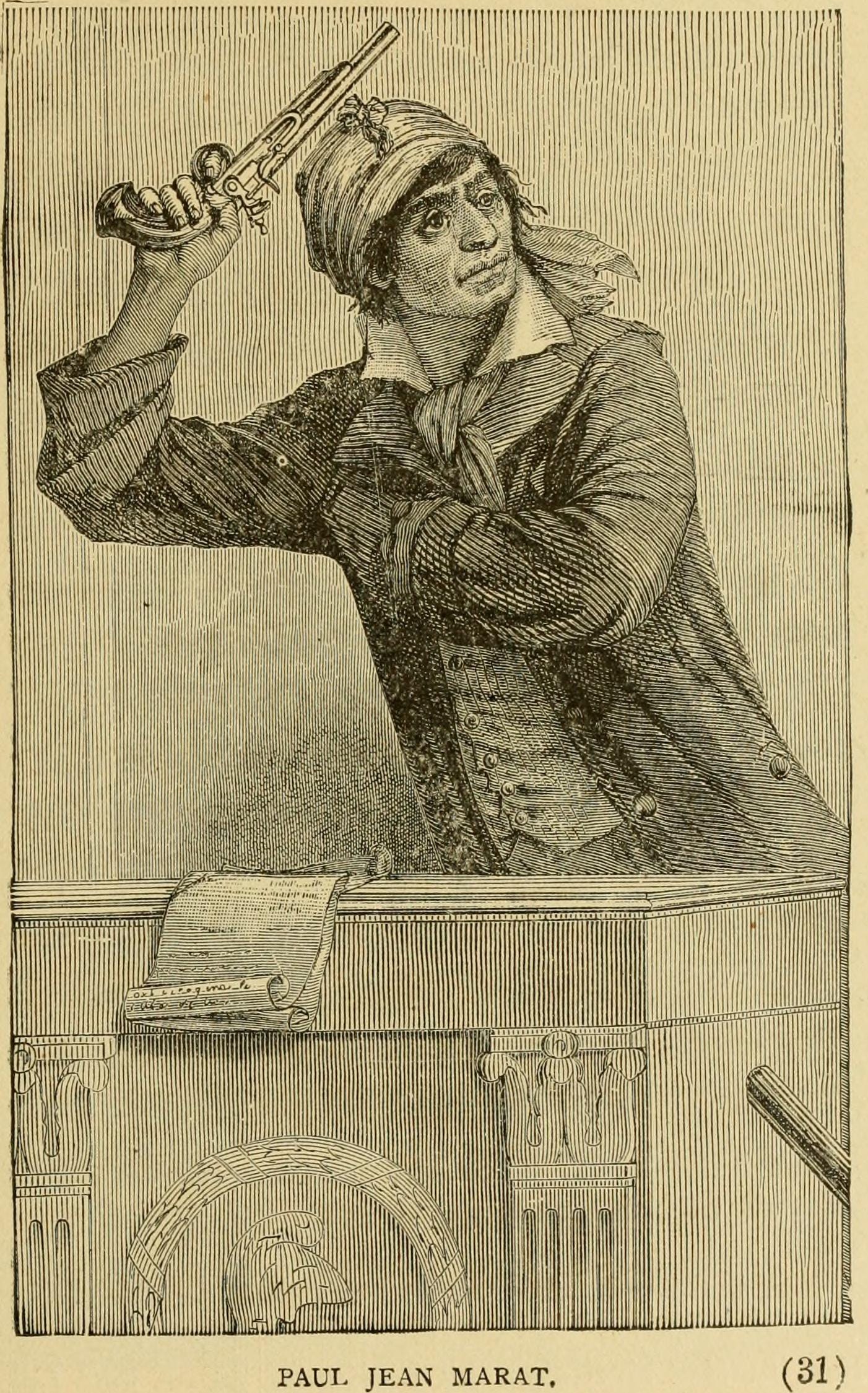

6. Marat’s disease

He was ill, and no one knew the name of his disease.

OK, spoilers, but Jean-Paul Marat will be the revolutionary with the most iconic death in this story. And by iconic, I mean Jacques-Louis David painted one of the most recognisable images of the Revolution, The Death of Marat.

He dies in a bathtub. And why he spent so much time in the bath has led to much speculation. His baths relieved his itchy and blistered skin, a condition Marat blamed on the damp squalor of his fugitive life in the sewers, cellars and catacombs of the capital.

Frustration blotched and mottled his skin.

What was wrong with him? Medical experts have speculated about the possibilities: syphilis, scrofula, scabies, leprosy, diabetic candidiasis, atopic eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, dermatitis herpetiformis, bullous pemphigoid, and histiocytic proliferative disorder.

Most recently, scientists have examined the blood-stained note he was holding when he died. You can read more about those investigations in the link.

7. The Angel of Death

'Oh, change the subject. I don't like Saint-Just.' 'Why is that, I wonder?' 'I don't think I like his politics. And he frightens me.' 'But his politics are Robespierre's – which means they are your husband's, and Danton's.'

You and me both, Lucile. Saint-Just is the most terrifying character in this book. He’s just turned 25, he’s the youngest deputy in the National Convention, a professional revolutionary, handsome and articulate, and 100% bad news.

He first appeared in “Liberty, Gaiety, Royal Democracy”, where Camille called him “a miserable revolutionary.”

‘He’s a republican, he says. I wouldn’t like to live in his republic.’

He is now Robespierre’s protégé and will later be known as the “Angel of Death”. Dark times lie ahead.

The French Revolution's Angel of Death (warning: spoilers!)

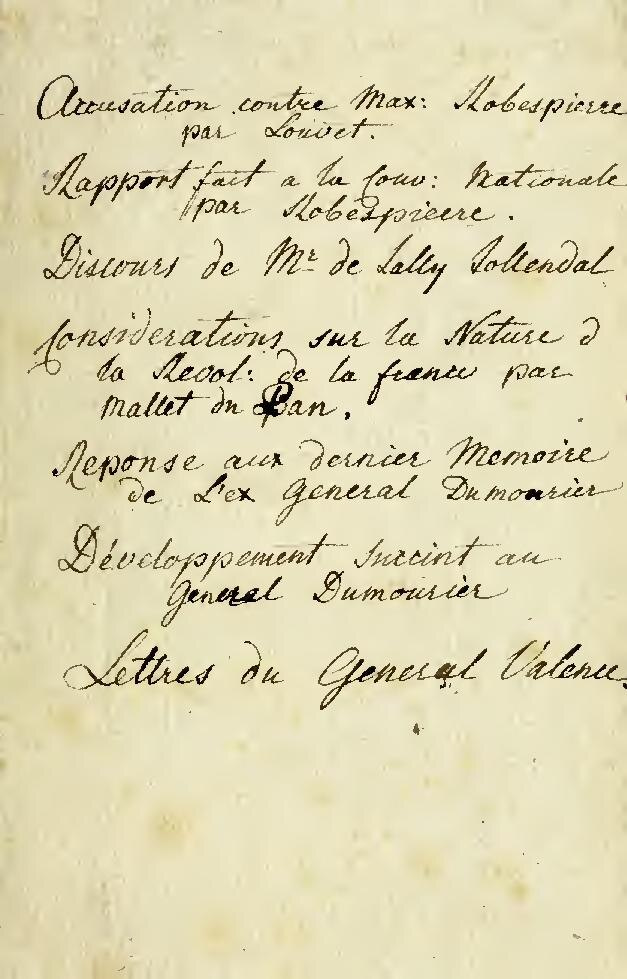

8. Robespierricide

‘I accuse you of having set yourself up as an object of idolatry: of having allowed people to name you in your presence as the only man who could save the nation - and of having said it yourself. I accuse you of aiming at being a supreme power.’

Remember Robespierre’s conspicuous absence on 10 August and later during the September massacres. He definitely did not want to be associated with these illegal and bloody acts. However, Jean-Paul Marat has called for a dictator to save the revolution, and Louvet’s accusations attempt to cast Robespierre as Marat’s candidate for despotism.

This is the subtext to this scintillating description of Max and Marat:

Robespierre met him – in passing, of course, he had always known him, but he had shrunk from closer contact. There was the danger that, if you talked with Marat, you would be blamed for him, accused of dictating his writing and fanning his ambition. And yet, one can’t pick and choose; in the present climate one must count up one’s friends. Perhaps from this point of view the meeting was not wholly successful, serving only to show how the patriots were divided. Robespierre’s body, young and compact, had a neat, feline tension inside his well-cut clothes; his emotions, or those emotions that might be worn on his face, were buried with the victims of September. Marat twitched at him across a table, coughing, a dirty kerchief wrapped around his head. He spluttered with passion, his grubby fist pumped, frustration blotched and mottled his skin. ‘Robespierre, you don’t understand me.’

So much of these two chapters involves these five revolutionaries (Max, Camille, Danton, Marat and Saint-Just) persuading each other and themselves into more violent orientations. OK, Marat needs no persuading. But see how every exchange shuffles Max, Camille and Danton towards more murderous positions.

‘But surely, in private, he and Robespierre have an antipathy for each other? Does that matter? Oh yes, it will matter, in the end.’

9. The visible exercise of power

Lucile does not entirely share the general feeling. She has enjoyed sweeping down grand staircases, the visible exercise of power.

And all this edging towards violence is because they are now in positions of power with nowhere to hide. Danton can’t shut himself in his office, and Robespierre cannot hide at the Duplays. As Claude said of Camille last week:

‘He has arrived now, he is the Establishment. Anyone who wants to make a revolution has to make it against him.’

Whether it is executing the king or arresting their opponents, power is now visible. Irrevocable decisions must be made. As trained lawyers, they understand the importance of justice being seen to be done. But what is justice now? Camille:

‘I don’t like this idea or ordinary crimes and political crimes. Our opponents can use it to murder us, just as we can use it to murder them. I don’t see what good the idea does. We ought to admit that all crimes are the same.’

10. Jacques Roux

‘Jacques Roux, this priest – but that’s not really his name?’

’Oh no – but then perhaps you think Marat is not mine?’

Marat’s name wasn’t really Marat – he was born Jean-Paul Mara in Prussian territory with Genevan and Sardinian parents. He francized his surname when he moved to France.

I don’t know what Roux’s real name was. Perhaps it really was Jacques Roux? Perhaps Mad Red Jack came from nowhere, condensed out of revolutionary air: an inevitable phantom of these terrible times?

A “red priest”, leader of the sans-culottes, and spokesperson for the enragés – “The madmen” who defended the urban poor against what they regarded as a bourgeois betrayal of the revolution by the National Convention.

Well, here’s a find: In 1989, Alan Rickman performed a monologue as Jacques Roux for the BBC. It’s a great watch if you don’t mind the spoilers:

Note, the public space is now awash with violent political rhetoric. Marat’s newspaper, of course. But also Max and Camille’s schoolfriend Stanislas “Rabbit” Fréron:

his opinions grew steadily more violent, as if it was a contest and he badly wanted to win; at times you couldn’t distinguish his work from Marat’s.

Then there is René Hébert’s alter-ego, the fictitious foul-mouthed furnace-maker, Père Duchesne. Camille hates Hébert, but notes that even Père Duchesne thinks Jacque Roux goes too far.

But they encourage each other, these people. Marat:

‘Let’s, as the women say, let’s get Christmas over, and then we’ll see what we can do to put this Revolution on the right lines. I wonder if our masters realize what assets we are? You with your sweet smile, and me with my sharp knife?’

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Five, Chapter IV. Blackmail & Chapter V. A Martyr, a King, a Child & Chapter VI. A Secret History.

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

They've forgotten what the revolution was for, haven't they? This is all about power play - and settling old scores. And sex, of course. But how does any of this help the man in the street? Of course, it doesn't. I think I'm probably beginning to side with Gabrielle.

My favourite line makes a link to the Wolf Crawl: "his emotions, or those emotions that might be worn" seems to be relative to 'arranging your face'. In many ways, what Mantel is doing in both is showing what goes on behind the history we know, so it shouldn't be a surprise.

And this is yet another section where we see how tough things are for women - in a variety of ways. Manon is held to different standards from men; Lucile seems to get very little back from Camille; and Gabrielle has Danton (which may be the worst position of the three).

When they were talking about how to change the law to get what they want, Thomas More's speech from 'A Man For All Seasons' cam to mind. When Rich says he would cut down every law in England to get to the Devil, More responds:

"And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned 'round on you, where would you hide, Roper, the laws all being flat? This country is planted thick with laws, from coast to coast, Man's laws, not God's! And if you cut them down, and you're just the man to do it, do you really think you could stand upright in the winds that would blow then? Yes, I'd give the Devil benefit of law, for my own safety's sake!"

I can helping thinking that our three 'heroes' should have taken note of that.

These two chapters were full of scenes showing how the different factions are evolving and complicating things - without this slow read I’d be fully lost! The book is so dense that for someone like me without much prior knowledge of the events and personalities involved in the revolution, it would be extremely challenging to make it cohere as a whole story without the help of the weekly context provided here. Am pleased to have persisted and gotten this far though - I am loving the writing and how she writes about power, intrigue and the little (or great) moral compromises those leading have to make. Thank you and keep up the good work.