Decree of the National Convention: 'The government of France is revolutionary until the peace ... Terror is the order of the day.'

last week | main page | reading schedule | cast of characters | further resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings.

This week, we are reading Part Five, Chapter IX. East Indians.

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

Late July, and Danton is off the Committee. He seems relieved rather than worried, but his old friend Fabre looks scared. Their closest ally on the committee is the ex-aristocrat Hérault. The next day, Robespierre reluctantly joins the Committee, followed by two old associates from Arras.

Now, it matters what Robespierre thinks of you. Danton is beyond criticism. But Hébert and Jacques Roux are “ultra-revolutionaries … agents of the enemy.” And Chabot is thinking of marrying the enemy. Max makes notes. Max has a list.

In September, the sans-culottes demand fixed prices, economic controls, and an end to private property. Danton and Robespierre work together to stop Jacques Roux’s radical revolution – but Danton refuses to return to committee work. Roux is arrested and kills himself. Danton falls ill.

Meanwhile, Fabre is panicking. He fears the Committees will uncover his unlawful involvement in the East India Company. Camille doesn’t want to know, but he takes Fabre’s fears to Danton before Danton leaves the city for Arcis. At home, his family welcome him and his new skimpy wife.

With Danton gone, Fabre takes the initiative. He delivers the conspiracy of dirty dealing to Robespierre and Saint-Just. He names Chabot, Julien and Hébert, and a pair of Jewish bankers. Max broadens the net to include Hérault. Once Fabre is out of the room, Saint-Just tries to drag Fabre’s name back into it. The two revolutionaries eyeball each other coolly.

At the Palais de Justice, Camille and his cousin Fouquier-Tinville compare notes as the jury considers its verdict on the widow Capet, Marie-Antoinette. Fouquier is feeling cheerful, so he doesn’t understand his cousin’s gloom.

For two boys from the provinces, he thought, we are doing extremely well these days.

16 October 1793. Marie-Antoinette is conveyed in a tumbril to her place of greater safety.

We have less than six months to live.

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then I recommend listening to:

During the summer of 1793, following the purge of the Girondins from the National Convention, power is consolidated in the twelve elected members of the Committee of Public Safety. Danton is not re-elected to the committee due to his moderate position and willingness to negotiate peace terms with Austria.

The journalist René Hébert (Père Duchesne) fills Marat’s shoes and overtakes the competition to embody the soul of the Parisian sans-culottes. On the one hand, Hébert demands that the revolution hurry up and execute Marie Antoinette, Brissot and the Girondins. However, Hébert also helps the Convention co-opt and neutralise the troublesome Enragés ultra-revolutionaries, led by people like Jacques Roux.

In September, the Enragés stage an insurrection, calling for price controls and swifter justice for the people’s enemies: mostly suspected aristocratic grain hoarders. Led by Danton and Robespierre, the Convention uses these demands to strengthen the Committee of Public Safety and suspend the new constitution:

The government of France is revolutionary until the peace ... Terror is the order of the day.

Joining Max Robespierre on the Committee are two enthusiasts for political violence, Collot d’Herbois and Billaud-Varennes. Another important addition, Lazare Carnot, brings in mass conscription, reorganises the army and helps turn the war around.

Robespierre worries that the Committee might be infiltrated by a traitor working for foreign powers. So when Fabre d’Églantine brings him fabricated evidence of a foreign plot, Robespierre joins the dots and suspects the de facto Foreign Minister, Hérault. As it turns out, Fabre d’Églantine is misdirecting attention away from his own misdemenours.

On 14 October, the Revolutionary Tribunal summons Marie Antoinette to trial. On 16 October, she is guillotined. Thanks to the Law of Suspects, the jails are filling up, and with Hébert’s newspaper baying from the sidelines, the Tribunal is ready to begin the trial of the Girondins.

Footnotes

1. My friend the General

He was lucky, Lucile thought, to get Westermann his command back, after that last defeat; Westermann is lukcy to be at large.

You may remember that François Joseph Westermann popped up earlier in our story when Danton was planning the insurrection of 10 August 1792. He was useful to Danton back then as the only associate of the Cordeliers with any military experience. Useful when you’re plotting the overthrow of the monarchy.

Flashforward to July 1793, and Westermann is lucky to have Danton in his debt and “overthrowing the monarch” on his curriculum vitae.

Because that summer, the Revolutionary Tribunal was busy executing military officers who weren’t showing enough revolutionary zeal. In August, they guillotined General Custine for negligence in command of the Army of the North. In September, they tried his replacement, General Houchard, for failing to press his advantage in recent French victories. Houchard will lose his head on 17 November.

Marat had denounced Westermann for his association with the disgraced traitor Dumouriez. But thanks to his friends of the Cordeliers, he escaped a trial and was instead sent to fight royalist rebels in the Vendée.

'To Liberty,' said General Dillon, feelingly. 'Long may we, if you know what I mean, be at liberty to enjoy it.'

As we saw last week, Arthur Dillon had also been arrested. He’s won his liberty thanks to Camille Desmoulins’ intervention. But his liberty won’t last, and Camille already senses his defence had been a mistake:

Camille knew that this summer he had made a bad move; he should have left Arthur Dillon to the Republic’s judgement. At the same time, he had demonstrated his personal power. But it was isolation he sensed, as mornings grew fresh, as logs were got in for the winter, as the pale gold sun anatomized the paper leaves in the public gardens.

2. Ultima Thule

Pytheas said that in the island of Thule, which Virgil called Ultima Thule, six days’ journey from Great Britain, there was neither earth, nor sea, but a mixture of the three elements, in which it was not possible to walk, or go in a vessel; he spoke of it as a thing which he had seen.

You can find this quote in Camille Desmoulins’ notebook, just before he quotes an aphorism of Hippocrates: “Life is short, art is long, opportunity fleeting, experience dangerous, judgment difficult.”

If I recall correctly, both this aphorism and Ultima Thule are mentioned in The Mirror and the Light. Cromwell thinks of the reformer Robert Barnes:

A worldly man, a clever man, but he is afraid to be in England now: as if she were Ultima Thule, where earth, air and water mix to form a jellied broth, and a night lasts six months, and the people dye themselves blue.

It is no coincidence: there is a similar atmosphere for Cromwell and Camille in the latter stages of both these books. The stable world feels formless and unsteady; an unnerving feeling that we have dropped off the map of the known world.

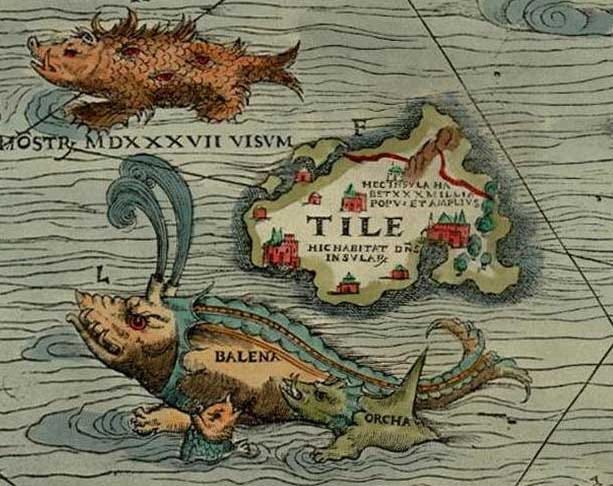

On Olaus Magnus’ 1539 Carta marina, the island of Thule appears beside the helpful annotation, “monster, seen in 1537.”

We are in September 1793, and here be monsters.

3. Vertu

‘Vertu. Love of one’s country. Self-sacrifice. Civil spirit.’ 'One appreciates your sense of humour, of course.' Danton jerked his thumb in the direction of the noise. 'The only vertu those bastards understand is the kind I demonstrate every night to my wife.'

It is an exchange that encapsulates the two men and their relationship, and perhaps more than anything else condemns Georges-Jacques to his fate: “Danton laughed at the idea of vertu”, Robespierre writes in his notebooks.

In her essay on Robespierre, Mantel writes:

There is a problem with the English word ‘virtue’. It sounds pallid and Catholic. But vertu is not smugness or piety. It is strength, integrity and purity of intent. It assumes the benevolence of human nature towards itself. It is an active force that puts the public good before private interest … Robespierre thought that, if you could imagine a better society, you could create it. He needed a corps of moral giants at his back, but found himself leading a gang of squabbling moral pygmies.

Which is how Robespierre’s love of vertu leads to the logic of terror. He sets himself a moral standard and finds everyone else incapable of measuring up. Robespierre persecutes everyone who fails the vertu test, and that’s everyone except Robespierre. He goes after those who want to slow things down and those who want to speed things up: the moderates and the ultra-revolutionaries.

No one can get it right in Robespierre’s world.

The decree was passed. The moment passed. And now, thought Danton, we ought to be able to bow and walk off stage. Weariness like a parasite seemed to burst into flower from his bones.

Significantly, at this moment, both Danton and Camille are overladen by weariness and dread. In contrast, Max has never seen more alive: “Each bout of sickness left him perversely strengthened, it seemed.”

4. The Reign of Terror

Antoine Saint-Just: ‘You must punish anyone who is passive in the affairs of the Revolution and who does nothing for it.’

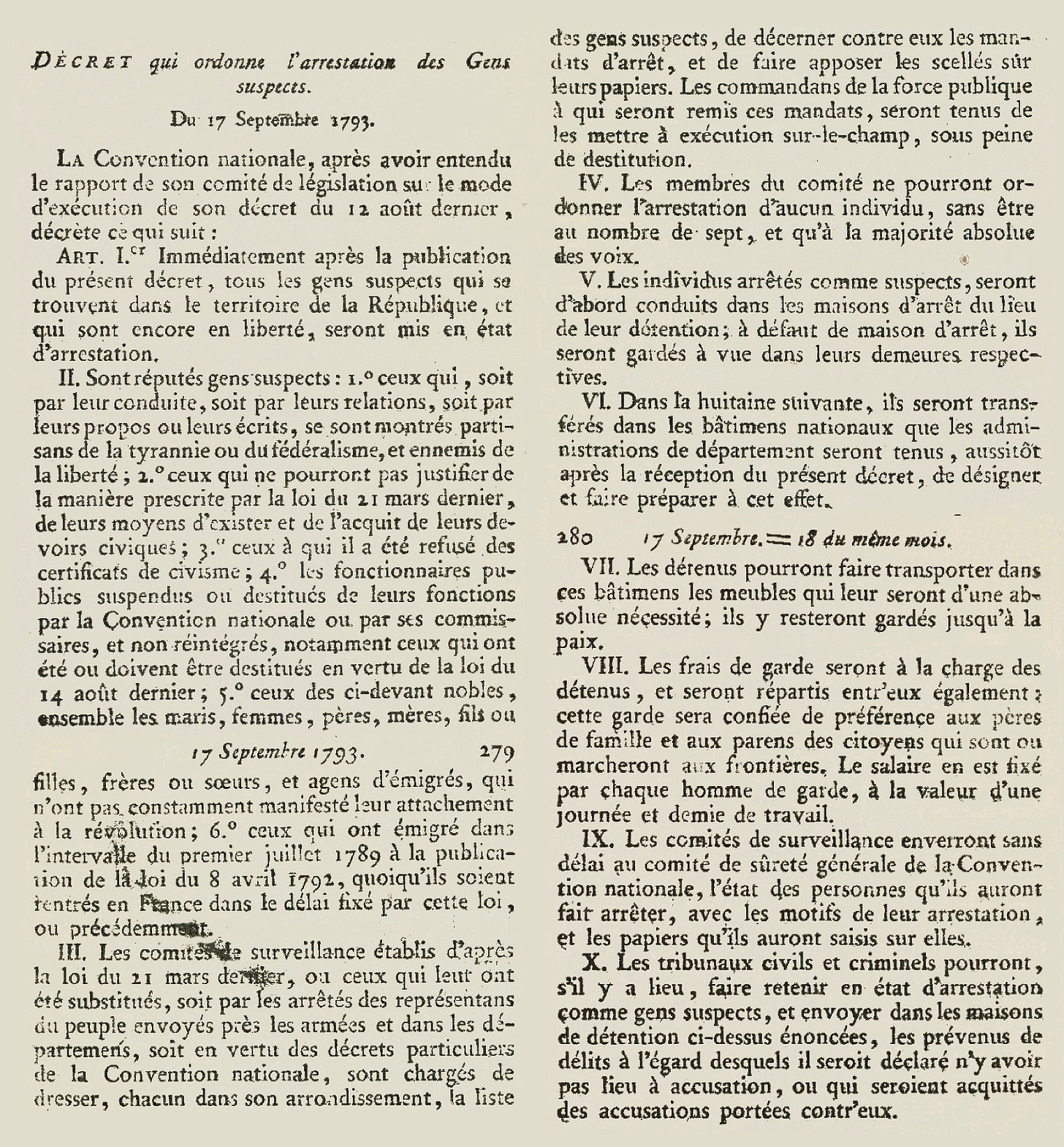

17 September 1793 is sometimes cited as the beginning of the Reign of Terror, a period of political violence that lasted until the execution of Maximilien Robespierre on 28 July 1794.

On 17 September, the Convention issued a decree that reversed the principle of “innocent until proven guilty” and demanded the arrest of anyone suspected of opposing the Revolution.

And what is the Revolution? The Constitution has been suspended, so the Revolution is the National Convention. And the National Convention is the Committee of Public Safety. And the Committee of Public Safety is Maximilien Robespierre.

Max is the Revolution, and we are well on the road to an authoritarian dictatorship.

Robespierre is becoming one of those people in whose company it is impossible to relax for a moment.

Over the next nine months, hundreds of thousands of people will be detained as “suspects” and 16,594 official death sentences will be dispensed.

5. Revolutionary Time

‘So they’ve changed the calendar,’ Danton said. ‘It’s too much for an invalid.’

It is too much for most of us, Georges-Jacques.

Initial plans to make 14 July 1789 the first day of the “Era of Liberty” were superseded in 1792 with the founding of the French Republic. Now, Year I began on 22 September, which so happens to also be the Autumnal equinox. This inspired Fabre d’Églantine to rename the months after the prevailing weather and agricultural calendar:

‘But Fabre has been asked to think up some ridiculous poetic names for the months. He plans that the first should be Vendémiaire.’

Vendémiaire is derived from the word vendemiaire, “grape harvester”, and is followed by Brumaire (the misty month) and Frimaire (the frosty month). Despite the republicans’ zeal for the decimal system, they retained 12 months of 30 days, followed by five or six Sansculottides or complementary days.

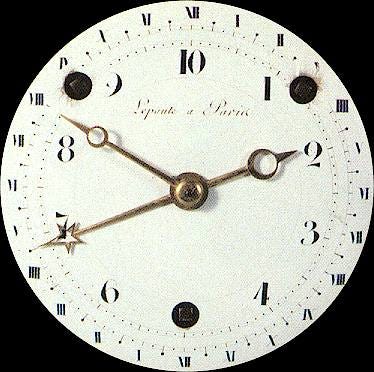

Each month now has three weeks of 10 days, not a popular decision among the peasantry, who are now required to work 9 days in 10. Each day was divided into 10 hours of 100 minutes. Seconds lasted 0.864 conventional seconds, and 100 of them made a minute.

New clocks will be required. In September 1793 (sorry, Vendémiaire in Year II), the calendar was officially approved and remained in use until Napoleon scrapped it in 1805.

‘In my household, it remains 10 October.’

Here also. We will not be adopting revolutionary time at Footnotes & Tangents.

The calendar was briefly reprised during the Paris Commune of May 1871. It lives on in the French dish Lobster Thermidor (named after a play set during the revolution), and in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Nûmenorean Calendar, in which the months are translated into elvish.

'Citizens.' Fabre beckoned. 'Word with you?' The irritation on Saint-Just's face deepened. Robespierre though of the pretty new calendar, and fetched up a wintery smile.

Robespierre’s fall takes place 10 months from now and is forever linked to this “pretty new calendar” by its name: the Thermidorian Reaction.

The 12 Months of the French Republican Calendar (Britannica)

6. East Indians

‘– you have heard of the East India Company? Good, because we have made quite a lot of money out of it.’

When asked about the challenge of turning the minutiae of Tudor administration into gripping historical fiction, Mantel said anything felt possible after explaining the East Indian Company fraud in A Place of Greater Safety.

In her essay on Robespierre, she calls it “a business of such farcical complexity that nobody could see the end of it, or plumb its depths.” Those depths instil fear into everyone, including Max, who sees it as evidence that the revolution is irredeemably corrupted by greed and private interests.

The French East India Company was set up to compete with its English and Dutch equivalents in Asia. The royal chartered company had been a corrupt financial mess, and was unable to withstand competition after the National Assembly removed its monopoly in 1790. In August 1793, the National Convention called time on the East India Company.

As it went into liquidation, members of the Convention extorted money from financial speculators involved in manipulating stock prices and selling short. They threatened the speculators with exposure, but they had to cover their tracks to avoid being exposed themselves. And at the centre of all this fraud, forgery, extortion, and profiteering was the chair of the committee in charge of the company: Fabre d’Eglantine.

Before his fellow “East Indians” could dob him in to the Committee of Public Safety, Fabre fabricated his own conspiracy designed to ensnare anyone who had any dirt on him. This is the “foreign plot”, and we will undoubtedly return to it and the East India Company in the next few weeks.

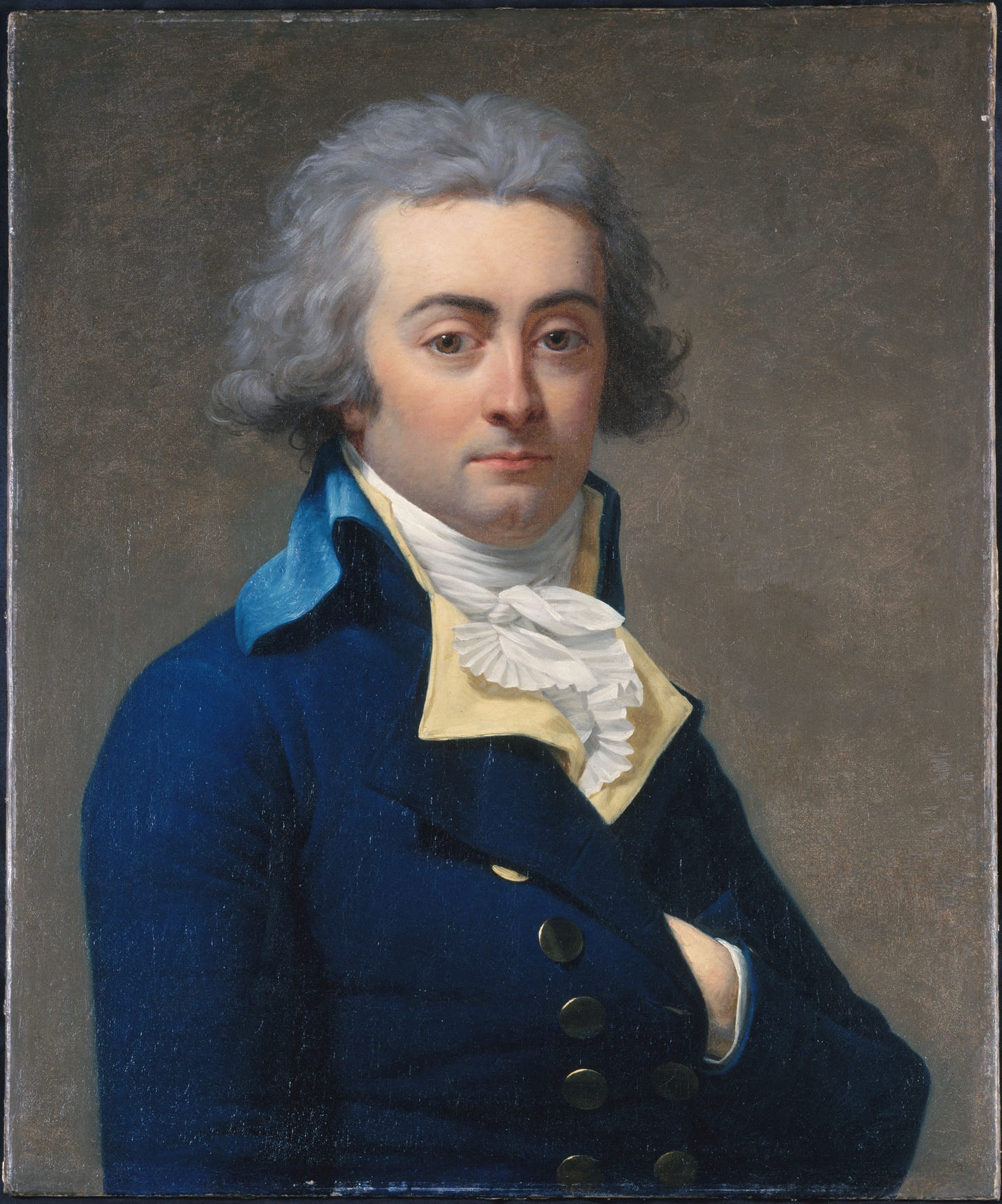

Max’s addition of Jean-Marie Hérault de Séchelles to the list of suspects perturbs Fabre:

A pity he suspects Hérault. I could warn him, but what use? Life anyway is so precarious for the ci-devants, perhaps his days were already numbered.

This chilly thought is like the first gust of autumn. Ci-devant refers to the fact that Hérault was formerly an aristocrat, and it is quite astonishing that an ex-noble is a member of the Committee of Public Safety in the summer of 1793. Remember, this is the dapper deputy of the National Assembly who fell in with Camille and Danton, embracing republicanism with gusto, and wielded a meat cleaver in the heady days of May 1789:

‘Oh yes,’ he said, and he gripped the cleaver and charged back into the crowds, ‘it beats filing writs, doesn’t it?’ He had never been so happy: never, never before.

Robespierre and Hérault are the best-dressed committeemen. But there is something unserious, self-deprecatory and ironical about Hérault. The Revolution is a bit of a jolly for this ci-devant. And there’s nothing Max hates more than a revolutionary who fails to take his job seriously.

7. Widow Capet

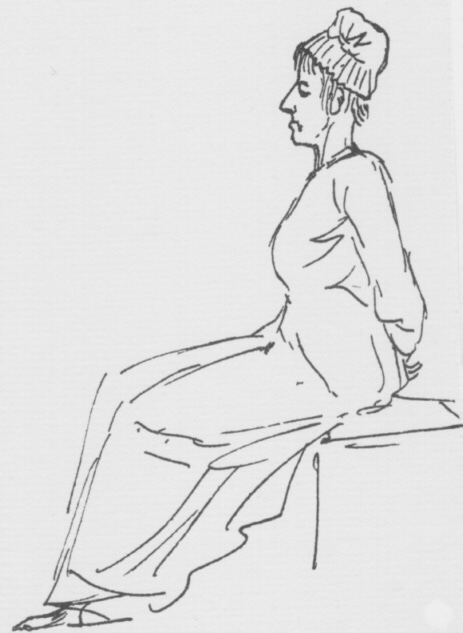

Her hands were tied again, and she was put into the cart. Under the shorn hair and the plain white cap, her tired eyes searched for pity in the faces around her. The journey to the place of execution lasted for an hour. She did not speak.

David sketched Marie Antoinette on the tumbril bound to the Place de la Révolution. As Mantel records, her final words were “Pardonnez-moi, monsieur. Je ne l'ai pas fait exprès” after stepping on the executioner’s shoe.

Everything is awful about this episode. Marie Antoinette’s son, Louis Charles or Louis XVII, is taken from his mother to be raised as a republican. Hébert and others extract a signed statement from him alleging his mother sexually abused him. Hébert’s alter-ego, Père Duchesne, calls her death “the greatest joy of all the joys.”

Camille is less joyous:

‘It hardly seems much, really, to be the summit of our ambitions. Cutting some dreary woman’s head off.’

The Prosecutor is Camille’s cousin, Antoine Fouquier-Tinville. He will still be the prosecutor when his cousin faces the Revolutionary Tribunal in a few months’ time. He cannot understand why our cousin looks so glum. But we can.

Think now of those post-Bastille days: Brissot in Camille's office, perched on the desk, Théroigne swishing in and planting a big kiss on his dry cheek. He was my friend, Camille thinks; then along came the gambling case, and we were suddenly on opposite sides, he made it personal, and I can't stand criticism. He knows this about himself; he either flares up or folds up, he takes some kind of offensive or – or what? 'Antoine,' he says to his cousin, 'I seem to know all forms of attack. But I seem to know no forms of defence at all.'

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Five, Chapter X. The Marquis Calls

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

I'll admit it: I'm a bit confused about who is one whose side, but I think that just reflects the state of the revolution (and the 21st Century, if we're making connections).

My bureaucrat head says "this is what happens when you don't have a proper plan". It's all conniving and settling scores - not only with the ancient regime, but with fellow revolutionaries. And the things they need to sort out - feeding people, first a start - are left on the 'too hard to do' pile.

Mantel really plays a blinder with Marie Antoinette. She's been icy cold and distant so far, but we really feel for her at the end - a victim, and an unnecessary victim at that.

And Mantel still manages to get the humour in with the family visit. You can imagine Louise wondering what kind of family she had married into. I do find myself noticing that the women seem focused on birth, but the men seem focused on death. Maybe it's a coincidence, but I suspect it's deliberate.

I've always known there was a new system for time during the revolution, but I'd never really thought how bonkers it was. Having a system of time that was out of step with the rest of the world doesn't seem the smartest move for a new state (and I know there's the Julian / Gregorian calendar to take into account as well). That's what happens when you put hotheads - idealistic or not - in charge.

Enjoy the bank holiday if you have one - for some of us, the next one isn't until Christmas!

I tend to wander about looking like the Great Unwashed but that hides a fascination with fabric. Consequently, I was delighted this morning to receive a Substack from Articles of Interest with the history of the French fabric, Toile de Jouy. Marie Antoinette used this fabric in her private rooms and one of the many designs was for the Fete de la Federation. But, best of all, the man who made Toile popular, Oberkampf, survived with his head intact. That always feels like a win.

If you're interested, read the whole thing or scroll halfway down for the Revolutionary bits.

https://articlesofinterest.substack.com/p/toile-de-jouy?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email#media-9a028f70-20ad-4034-bd0b-cd2ba336387a

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/221956