APOGS #7: Enthusiasts for murder

Part Three, Chapter I. Virgins (1789)

‘Where do they come from, these people? They’re virgins. They’ve never been to war. They’ve never been on the hunting field. They’ve never killed an animal, let alone a man. But they’re such enthusiasts for murder.’

Last Week | Main Page | Reading Schedule | Cast of Characters | Further Resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings. And for the full experience, read online.

This week, we are reading Part Three, Chapter I. Virgins (1789).

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

This week begins with D’Anton taking the initiative and pretending to be “Captain d’Anton, of the Cordeliers Battalion.” Why not? “The government of the city is in the hands of anyone who turns up and says, ‘I’m in charge.’” He arrests the new governor of the Bastille and makes an impression on a sleepy Lafayette. Bailly is made Mayor of Paris and welcomes Louis back to his capital. “The people have reconquered their King,” he tells Louis.

Meanwhile, Lucile finds the now-famous Camille irresistible, while Desmoulins himself is exhausted by his dreams. He asks his friends what they think of each other, and Danton and Robespierre keep their opinions to themselves. On the streets, there are more lynchings. More heads on spikes.

4 August 1789. Feudalism is abolished. Camille writes it up as vera beata nox, oh truly blessed night! Marat says it’s a sick joke, a bit of myth-making. The Revolution isn’t over; it’s only just begun. And what we must do, he assures Camille, “is cut off heads.”

In the Rue des Cordeliers, Lafayette recognises D’Anton as now the official president of the district and a captain in the National Guard. What will he do with his new power? What is best or what is right? Gabrielle assures Camille that they will always be the same thing.

Camille joins Robespierre and other liberal deputies at the Breton Club in Versailles. Robespierre is the “Candle of Arras”, and Camille is a “mob-orator” who terrifies them all. They retire to dinner with Mirabeau, who is riding high and living well. Afterwards, over cards, Camille learns that British money is funding their revolution.

“There were fourteen at table. Tender beef bled on to the plates. Turbot’s slashed flesh breathed the scent of bay leaves and thyme. Blue-black shells of aubergines, seared on top, yielded creamy flesh to the probing knife.”

Camille’s incendiary pamphlet comes out in September. He styles himself as the Lanterne Attorney, the voice of the iron gibbet of a busy and bloody July. Lafayette would have Camille reduced to “a little red stain on the wall.” Mayor Bailly says Camille is protected by Danton and the Cordeliers. Camille is now a celebrity.

October. Fears grow that the King is planning either to resist or escape the Revolution. President Danton calls for the King to be brought to Paris, but then decides to hide himself in his office. So, instead, Lafayette is coerced by the National Guard to fetch Louis to the capital. Lafayette vows to protect the King, but is asleep when the mob take over events.

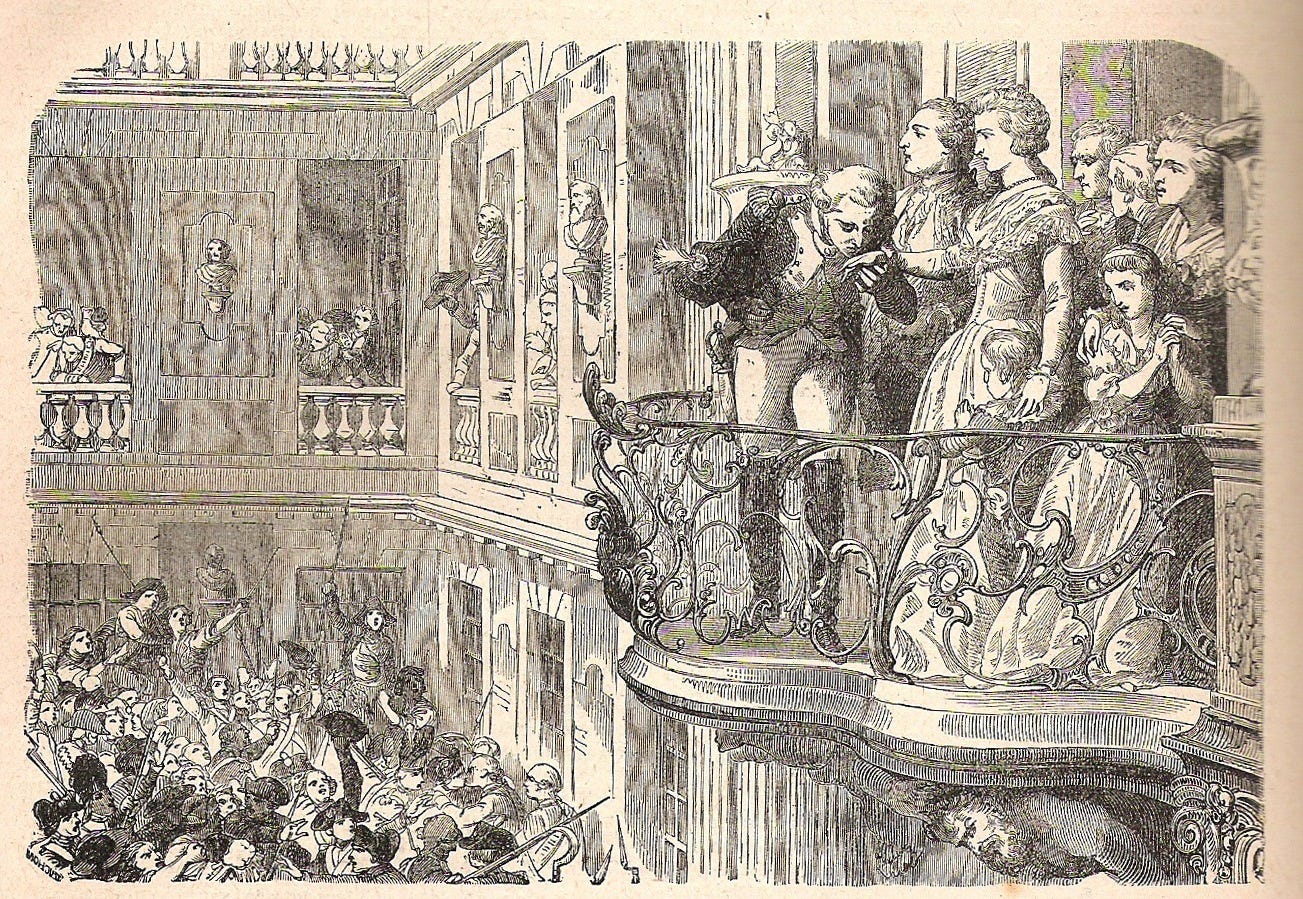

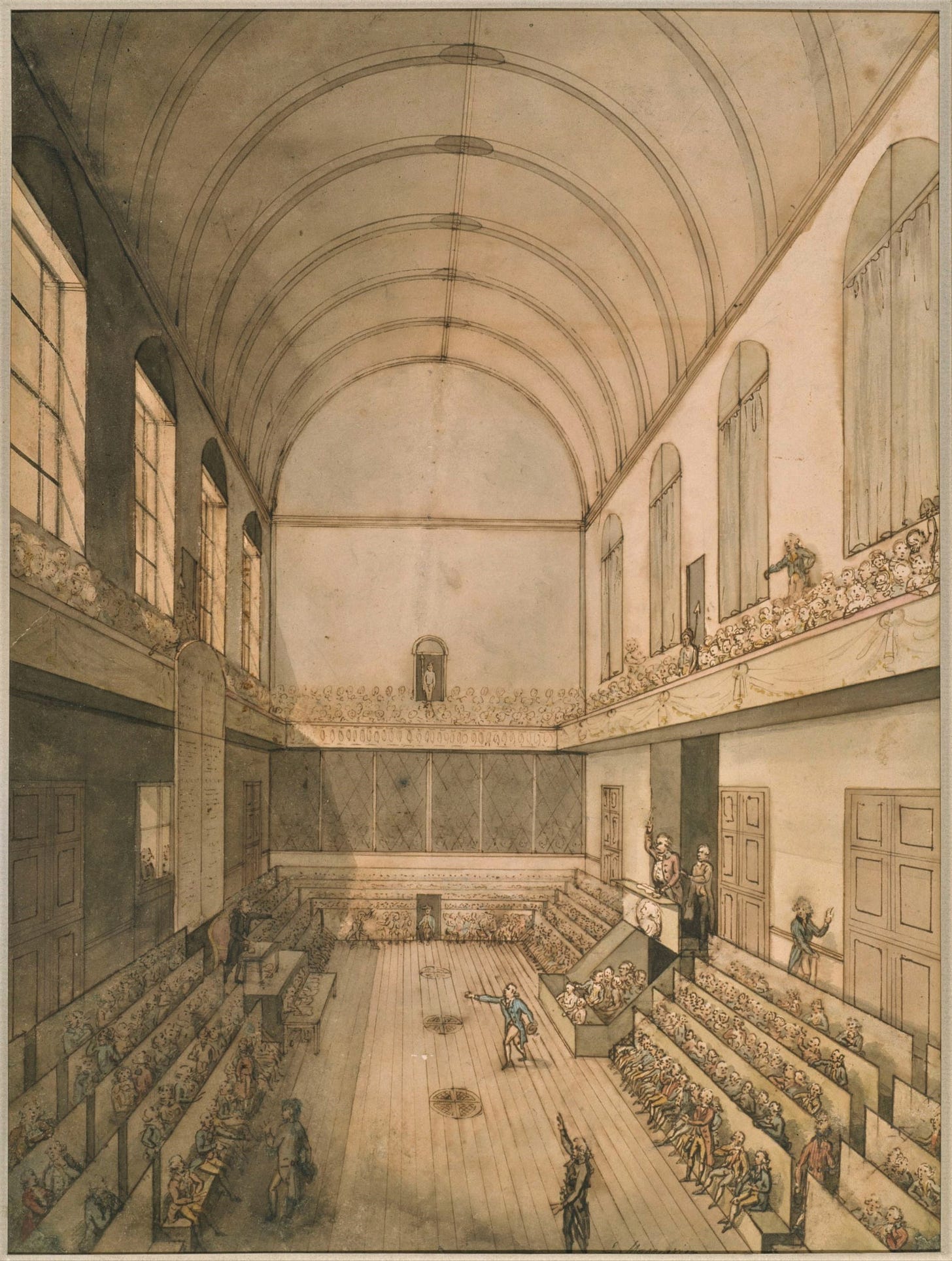

The National Assembly relocate to the Riding-School in Paris. The Breton Club meet in a building once occupied by the Dominicans, colloquially known as the Jacobins. At the Riding-School, the royalists sit on the right, the patriots sit on the left.

On the Rue Condé, Lucile, Adèle and Annette impersonate Camille, Danton and Robespierre. At dinner, Claude watches fearfully as these revolutionaries fraternise with his daughters.

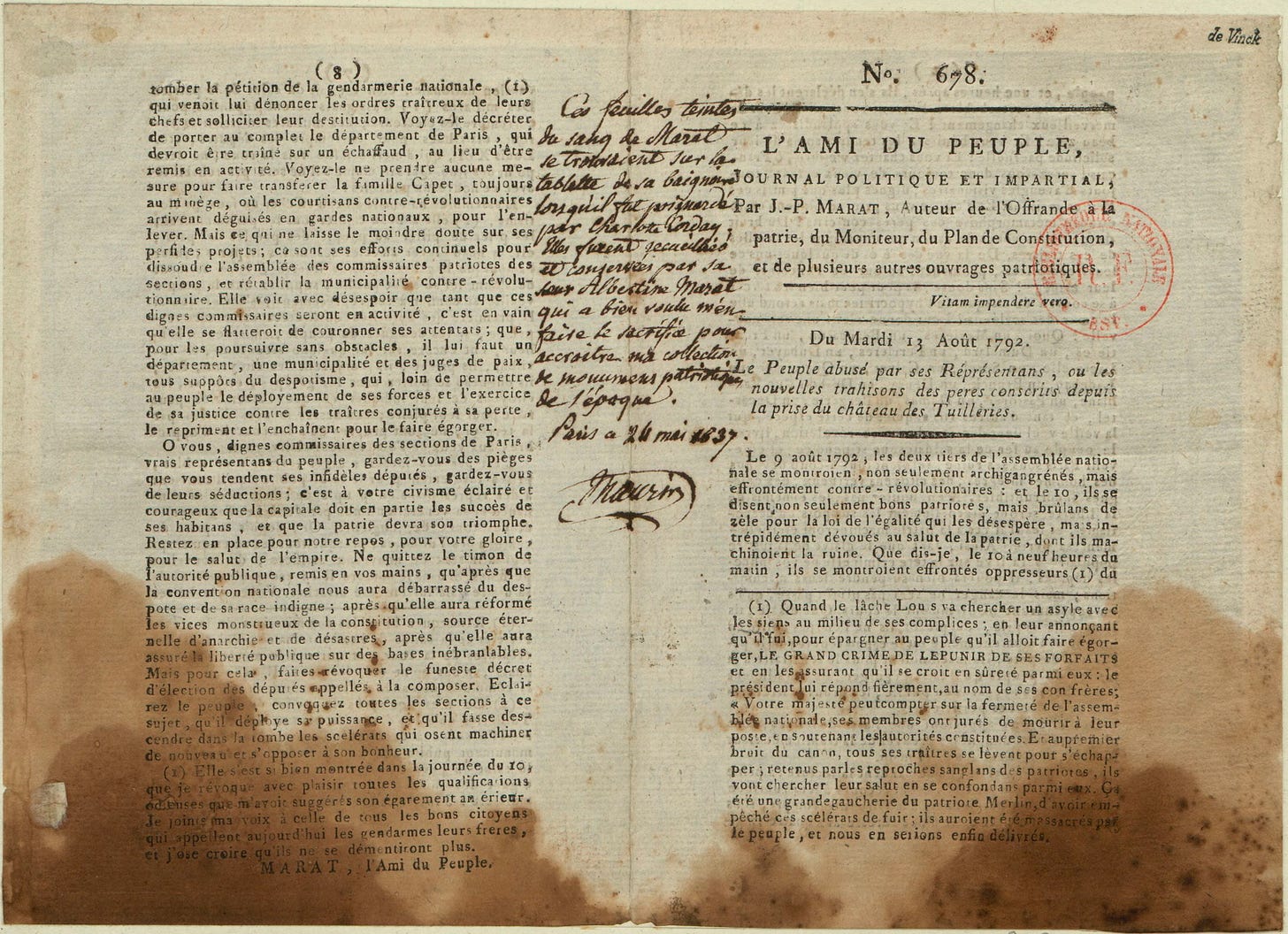

Camille launches his newspaper. It is more libellous than Brissot’s serious publication and has a better title than Marat’s rag. René Hébert threatens to start his own newspaper for the man in the street. Camille discovers his true vocation, exercising “his fine art of mockery, vituperation and abuse.”

While Camille writes, Lafayette takes hold of the Revolution. The Duke of Orleans is sent packing to London, and Mirabeau is sidelined. Meanwhile, Maitre G-J Danton quietly pays off his debts sixteenth months early. “What in God’s name is George-Jacques up to?” wonders his father-in-law.

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then I recommend listening to:

12. The Great Fear

The day after the Bastille falls, the king is told that he cannot deploy the army against Paris without risking widespread mutiny. By doing nothing, he concedes that an absolute monarchy no longer governs France. Lafayette is put in charge of the new National Guard and adds the royal Bourbon white to the blue and red cockades.

The National Assembly is also wary of mob rule and tries to take the initiative. The deputies now coalesce into factions, with the conservatives and moderates allying against the less unified radical Breton Club.

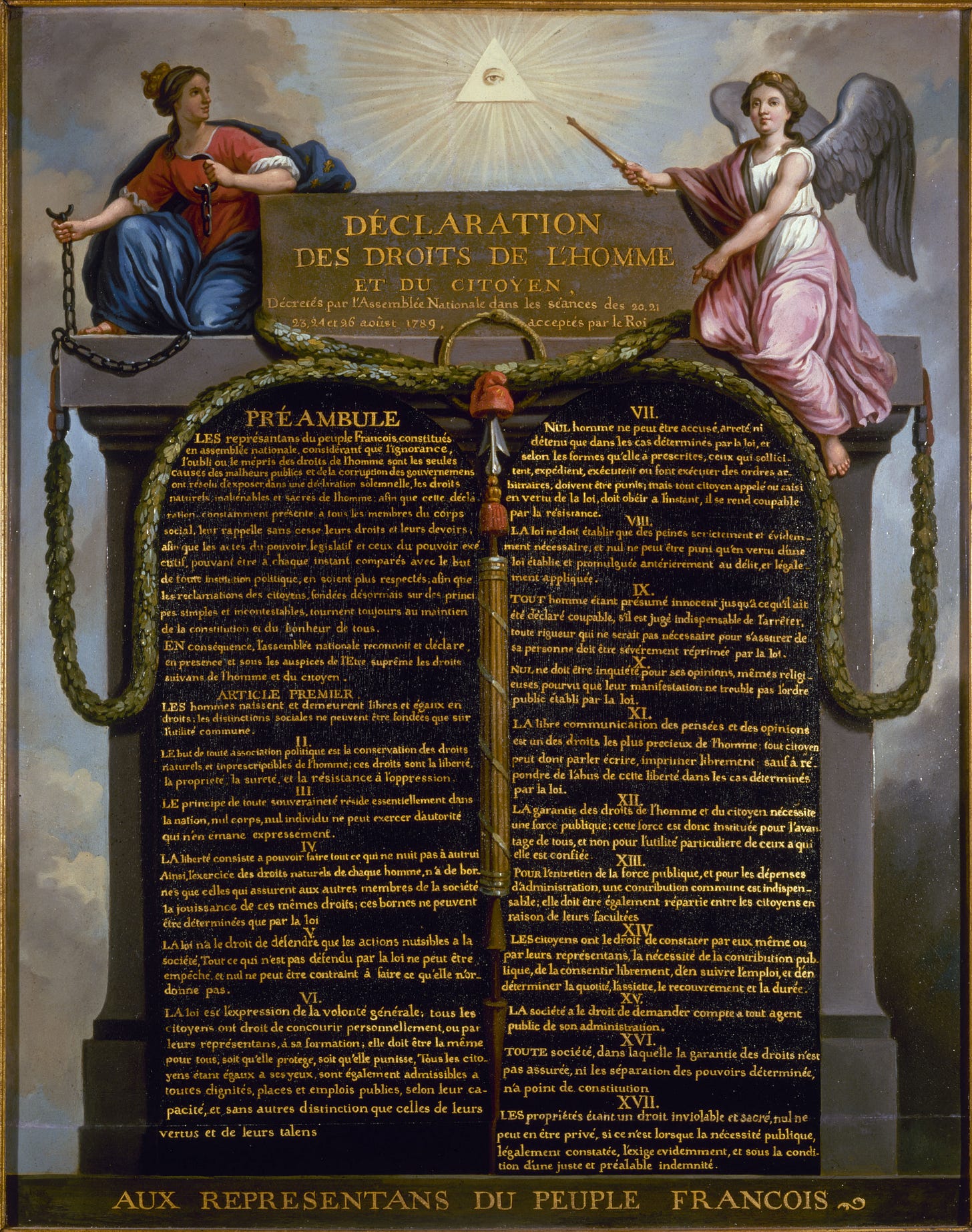

But late on 4 August, the radicals take over business and trigger a bonfire of feudal rights, with deputies outdoing each other to dismantle the old regime. In its place, they draft the Rights of Man, a stirring but ultimately vague and aspirational manifesto for the Revolution. Debates continue over the extent of the king’s veto.

Things boil over again in October. Bread prices are rising, and rumours reach Paris that the king’s bodyguard has desecrated the tricolour cockade. On 5 October, a procession led by Parisian women sets off to Versailles, followed by the National Guard, to the dismay of its commander-in-chief, Lafayette.

At Versailles, the women invade the National Assembly and force their way into the palace. The queen narrowly escapes a lynching, and the king agrees to move to the Tuileries Palace in Paris. The National Assembly follow, setting up in the Salle du Manège – the Riding-School.

In Paris, there is an explosion of civil society as different factions form clubs and societies and start newspapers. The radical deputies from the Breton Club found the Society of the Friends of the Constitution – known hereafter as the Jacobin Club. Affiliated clubs form across the country, and the Jacobins quickly become the most organised, popular and powerful organisation within the Revolution.

Footnotes

1. “Tell many people that your reputation is great”

'It's just the sort of game people around here like,' Pare said. 'I should think they really will make you a captain in the militia, d'Anton. Also, I should think they'll elect you president of the district. Everybody knows you, after all.'

Somehow, I had missed this detail on all previous readings: D’Anton is lying to Soulès and Lafayette about being the captain of the Cordeliers Battalion. Right now in Paris, the city is in the hands of anyone who turns up and says, '“I’m in charge.” It’s a confidence trick worthy of Thomas Cromwell, and made all the more audacious because it involves questioning Soulès’ claim to be the new governor of the Bastille!

A version of these events took place, helping to elevate Danton’s popularity among the Paris revolutionaries. The excellently named Prosper Soulès will not prosper. The last governor of the soon-to-be-abolished Bastille, Soulès, will be guillotined during the Terror, a couple of months after Robespierre sends Georges Jacques Danton to the guillotine.

He said to d'Anton, 'What do you think of Robespierre?' 'Max? Splendid little chap.' [...] He said to Robespierre, 'What do you think of d'Anton?' Robespierre took off his spectacles and polished them. He mulled over the question. 'Very pleasant,' he said at length.

Read: More on the National Guard (Alpha History)

Read: “He Roared” by Hilary Mantel (London Review of Books)

2. À la lanterne

M. Soulès eyes were drawn irresistbly to the Lanterne – a great iron bracket from which a light swung. At that point, not many hours earlier, the severed head of the Marquis de Launay had been kicked around like a football among the crowd. ‘Pray, M. Soulès,’ d’Anton suggested pleasantly.

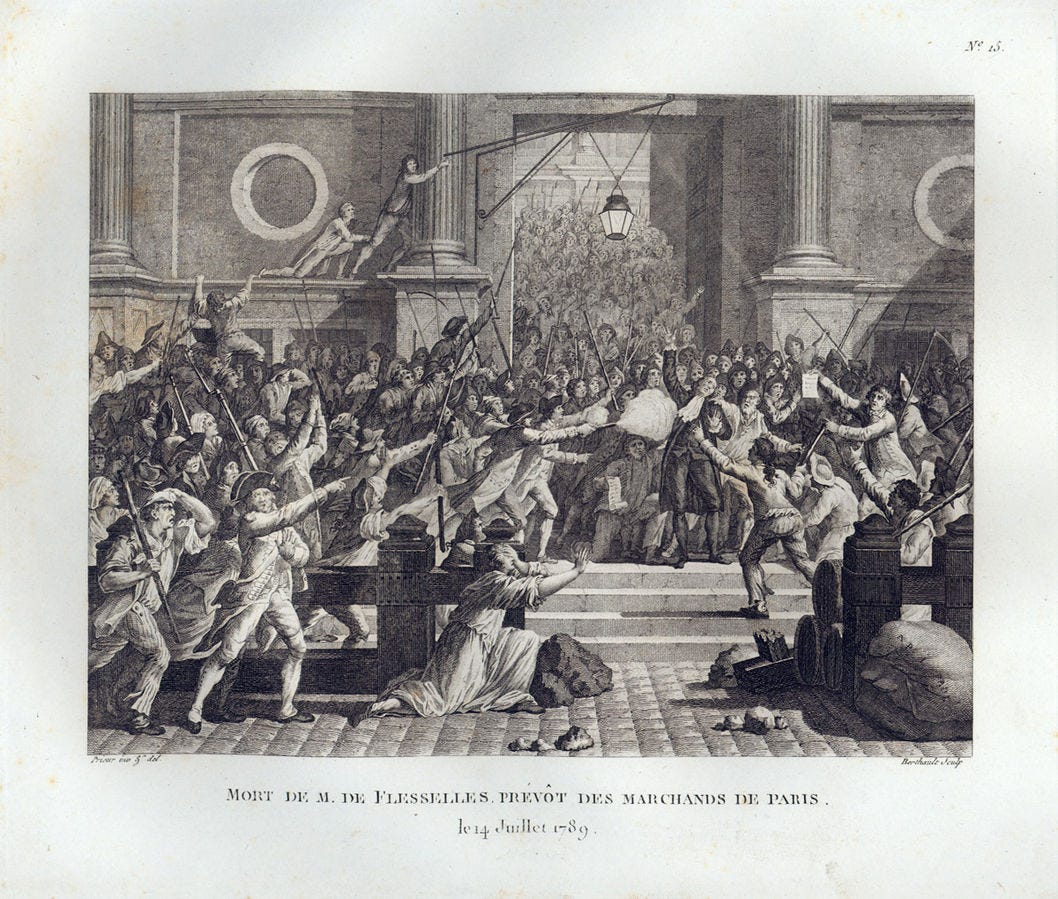

Hilary Mantel has Soulès look despairingly at the lamp post in the Place de Grève outside City Hall. It is worth noting that at this stage, 15 July 1789, no one has been hanged from the Lanterne. The first two high-profile casualties of the Revolution were shot and then decapitated on 14 July: the Governor of the Bastille, Marquis de Launay, and the Provost of Paris, Jacques de Flesselles.

What Soulès senses is a Mantelian ghost, a spectre from the future. On 22 July, ex-minister Joseph Foullon de Doué and his son-in-law Bertier de Sauvigny were hanged from the Lanterne.

“À la lanterne” became a revolutionary slogan equivalent to English cries of “String them up!" or "Hang 'em high!". Before the guillotine, the lamp post was the symbol of street justice. The bloodthirsty sans-culottes will later sing:

Ah! ça ira, ça ira, ça ira

les aristocrates à la lanterne!

Ah! ça ira, ça ira, ça ira

les aristocrates on les pendra!

Ah! It'll be fine, It'll be fine, It'll be fine

aristocrats to the lamp-post

Ah! It'll be fine, It'll be fine, It'll be fine

the aristocrats, we'll hang them!

Here’s Edith Piaf belting out the revolutionary song at the gates of Versailles:

The National Assembly, the Mayor of Paris and Commander-in-Chief Lafayette are horrified by these lynchings. And in this context, Camille Desmoulins makes his name as the Lanterne Attorney, telling Parisians that:

I've always been here. You could have been using me all along!

It’s a chilling provocation to more violence, inspired by a conversation with Dr Marat in “a dark corner” of a “dark bar”. Marat:

‘You see what we must do, Camille, is to cut off heads. The longer we delay, the more we will have to decapitate. Write that. The necessity is to kill people, and to cut off their heads.’

Respectable men like Claude Duplessis and Jean-Nicolas Desmoulins are horrified. They hope their womenfolk will be likewise dismayed. Camille’s mother breaks the news to Jean-Nicolas: “How little you understand women!” On the contrary, Rose-Fleur keeps Camille’s pamphlet on her sewing table, and Lucile Duplessis relishes “his unrespectability.”

3. An Irishman and a billiard table

An old man, shrunken and bony, with a long white beard, is paraded through the city to wave to the crowds who still hang about on every street. His name is Major Whyte – he is perhaps an Englishman, perhaps an Irishman – and no one knows how long he has been locked up in the Bastille. He seems to enjoy the attention he is getting, though when asked about the circumstances of his incaraceration he weeps. On a bad day he does not know who he is at all. On a good day he answers to Julius Caesar.

There were only seven prisoners liberated from the Bastille on 14 July. One of them was an Irishman called James Francis Xavier Whyte who fought against the English in the Seven Years’ War. After suffering a mental breakdown, his family paid to have him committed to first Vincennes and then the Bastille. After his “liberation” he joined the Marquis de Sade in the Charenton insane aslym.

‘I myself have heard of a billiard table that went in twenty years ago and has never come out.’

Simon Schama mentions the billiard table in Citizens, and Dominic Sandbrook refers to it in The Rest is History podcast. Does anyone know what happened to it? As a tangent, I am reminded of the ill-fated billiards room in The Siege of Krishnapur.

4. A splendid spectacle

At Astley’s Amphitheatre, Westminster Bridge (after rope-dancing by Signior Spinacuta) An Entire New and Splendid Spectacle: THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

Signior Spinacuta was Antonio Bartolomeo Spinacuta, a Venetian tightrope walker. He performed with his Swedish wife Helena, born Ellna Persdotter, and in 1786 released the first hot air balloons in Sweden.

The symbolism of tightrope walkers and revolutionaries is noted.

I love this window on the French Revolution viewed from the safety of the English box office. Chaos in Paris provided fodder for London’s theatres in the summer of 1789. At the Royal Circus, one could see “The Triumph of Liberty; or, the Bastille”, while Sadler’s Wells put on a production called “Gallic Freedom; or, Vive la Liberté.”

5. British spies

‘How annoyed Mr Miles and the Elliots would be, if they knew what I did with the King of England’s money.’

Camille learns that the radical deputies are taking money from the British government. Grace Elliot is a Scottish courtesan and erstwhile mistress to the future George IV of England and the Duke of Orléans. She will later help aristocrats escape to England, but is currently looking after Britain’s interests in France.

Read: Elliot’s Journal of my life during the French Revolution

Tangent: Watch a discussion of Grace Elliot’s portrait at the Frick

William Augustus Miles is a secret agent for the British Prime Minister William Pitt, tasked with taking advantage of the situation to prise apart the alliance between France and Spain.

6. Worry and wonder

The general was a kind man. He had undertaken to worry and wonder about Camille, and from that night on – at intervals, over the next five years – he would remember to do so. When he thought about Camille he wanted – stupid as it might seem – to protect him.

Arthur Dillon was descended from Franco-Irish aristocracy and was the Governor of the French colony of Tobago. In the National Assembly, he represented the Caribbean island of Martinique. He’s an aristocrat who supports a reformed monarchy under a democratic constitution.

He will become friends with Camille Desmoulins. A curious feature of Camille’s life is that he acquires a varied assortment of friends across the political spectrum. Contrast this with Robespierre, who has no real friends (except Camille). Despite (or because of) his bloodthirsty pamphlets, his friends feel a strange desire to protect him.

We are meeting Arthur Dillon here because he will play a significant part in Camille’s story later in the book.

7. Left and Right

The stricter upholders of royal power sat on the right of the gangway; the patriots, as they often called themselves, sat on the left.

Here is history in the making: If you have ever wondered where the political terms Left and Right come from, it all began in this poorly ventilated room in the Tuileries Gardens. Those defending the status quo gathered on the right. Those bent on upending everything sat on the left.

The move from Versailles to Paris radicalised the Revolution and pushed more people to the extremes. The moderates who held sway in Versailles are now less significant than the Jacobins, backed up by Parisian crowds and radical newspapers. Their opponents are conservative monarchists, and we will hear more about them next week.

Before leaving Versailles, the National Assembly had passed the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Its architects had been Lafayette, Thomas Jefferson, and the Abbé Sieyès. It crucially made a distinction between active and passive citizens, excluding the majority of people from the political process.

The Jacobins rejected this distinction in favour of a much broader franchise. This will be one of the key political divisions in the events to come.

8. The People’s Friend

Of course, Marat was the same, always changing his title, for various shady reasons. He had been the Paris Publicist, was now the People’s Friend. A title, they though at the Révolutions, of risible naïveté; it sounded like a cure for the clap.

Mantel may be thinking of Poor Man’s Friend, the cure-all ointment produced by Dr Giles Lawrence Roberts of Bridport. Dr Roberts claimed it cured scrofula, also known as the King’s Evil, because the English and French kings professed to be able to heal by their royal touch. Poor Man’s Friend features in a marvellous little book by Alan Garner that we will read next year.

Tangent: Read more about Poor Man’s Friend.

Camille’s new journal is named Révolutions because, besides France, there are currently republican revolts in Brabant (modern-day Belgium) and Liège.

This chapter closes with Camille’s flourishing writing career. Of the three friends, Robespierre has the purest belief in the Revolution. Danton mostly sees it as a form of career advancement. Camille regards it as an opportunity to put poison pen to paper and do what he does best:

When it was time to write, and he took his pen in his hand, he never thought of consequences; he thought of style. I wonder why I ever bothered with sex, he thought; there’s nothing in this breathing world so gratifying as an artfully placed semi-colon. Once paper and ink were to hand, it was useless to appeal to his better nature, to tell him he was wrecking reputations and ruining people’s lives. A kind of sweet venom flowed through his veins, smoother than the finest cognac, quicker to make the head spin. And, just as some people crave opium, he craves the opportunity to exercise his fine art of mockery, vituperation and abuse; laudanum might quieten the senses, but a good editorial puts a catch in the throat and a skip in the heartbeat. Writing’s like running downhill; can’t stop if you want to.

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Three, Chapter II. Liberty, Gaiety, Royal Democracy (1790).

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

Oh, I get to be first with 'there’s nothing in this breathing world so gratifying as an artfully placed semicolon'. I wondered how much of this was Mantel speaking through Camille.

Along with many others, I'm firmly in the befuddled camp.

I found the quotation at the beginning of the chapter really helpful: it gave me a clue what to look out for.

What I'm finding interesting - if a little tricky to follow - is the sense of absolute chaos. You can see that things are already basically out of hand, so when it trips into the Reign of Terror, it's not really going to be a surprise.

The line from Harold Macmillan about "Events, dear boy" comes to mind. There are so many things happening, not necessarily directly related but which will be connected in retrospect. Although it's a bit Greek drama the way we hear about lots of things rather than see them, that probably puts us in the same position as many of the characters.

I can't help thinking that much of the current populism feels like an echo of these events: and surely a warning to those stirring up anger that things may not go as they plan. It's the way things turn on a sixpence that is shocking. One minute the crowd is baying for blood, the next there are shouts of Vive la Reine!

I like the way that - so far, at least - we don't really get a view of Marie Antoinette. We get people's views of her, but very little direct - and that puts us in the same position as most of the people.

The Marat line is chilling, and probably reflects what many people think when they lead revolutions. I remember hearing somebody talking at the time about the Ceaușescus, saying that if they hadn't been killed immediately it may have led to further bloodshed. I'm not totally convinced - and the deaths of Louis and Marie Antoinette didn't exactly slow things down.

But, after all that, we get the semi colon. It's Heaven.