APOGS #19: Nothing but a machine

Part Five, Chapter XI. The Old Cordeliers & Chapter XII. Ambivalence

I don't laugh any more: I don't play at being a cat; I never touch my piano; I have no dreams; I am nothing but a machine now.

last week | main page | reading schedule | cast of characters | further resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings.

This week, we are reading Part Five, Chapter XI. The Old Cordeliers & Chapter XII. Ambivalence.

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

December 1793. Lucile is writing her diaries; Camille is writing the first issue of his new publication, the “Old Cordelier.” It’s going to criticise the Terror, and it’s got Max’s approval – as long as Robespierre gets to check the proofs. Danton is on board, as long as he doesn’t have to be in the same room as Max.

The first issue is a success. Deputies from the Plain congratulate Camille, who is warming to his topic. “He could be himself now.” Meanwhile, Robespierre seems happy to let the factions fight it out – as the National Convention grants absolute power to the Committee of Public Safety.

The third issue compares the Terror to the reign of Tiberius. It says anyone can be a suspect in this Republic. Max complains that Camille is defaming the revolution, and Camille tells him to his face, “Stop the Terror.” Hébert calls for Desmoulins’ head.

Hérault de Séchelles returns from Alsace, and no one will see him. He presumes the worst and attends the executions to learn how to die. Toulon falls, with the help of Napoleon. The Old Cordelier proposes a new Committee of Mercy to review the activities of the Tribunal. Éléonore Duplay tells Max that they want to force his hand, and Danton is behind it all.

Robespierre’s proposal for a Committee of Justice is voted down. When Camille comes to call, Max won’t see him. He gives Eléonore Duplay a farewell kiss. Saint-Just is back, and Hérault resigns from the Committee, telling Camille that the policy of clemency may come too late for him.

Saint-Just works on Robespierre. He brings evidence that Fabre was involved in the East India Company fraud. He wants to bring Danton and Camille before the Tribunal, and Robespierre agrees that Camille’s conduct must be investigated. Fabre is arrested.

The fifth issue of the “Old Cordelier” attacks Hébert, Barère and Collot. At the Jacobin Club, Robespierre accuses Camille of “political heresy” and forces him to recant. The Jacobins call for Camille’s head: “Guillotine him!”

Robespierre and Danton meet. Danton tells him the rumours circulating about Max and Camille’s special friendship. When Robespierre asks Danton to abandon Fabre, Danton appears to cry. He tells Max that he is not human; he has no life in him.

Hébert attempts to scare Camille by arresting his father-in-law and spreading the rumour that Desmoulins is sleeping with Annette Duplessis. Camille takes the fight to Hébert in the Convention and Vadier at the Tuileries. Robespierre clasps Camille’s hands and wishes Père Duchesne to hell.

Max falls ill and excuses himself from the Committee. Robert Lindet brings him news of food shortages and Hébert’s moves towards insurrection. Robespierre resolves to crush the factions, Hébert and Danton. Lindet warns Danton. One last meeting between him and Max before a sickened Danton quits the city for Sèvres.

Hébert is arrested, tried and executed.

In Sèvres, deputies come and go, asking Danton to return. General Westermann is in touch. There is talk of a military coup. But when the old Cordeliers, Camille and Legendre, arrive, they tell him to run. Danton says no, not this time.

In Paris, Saint-Just looks over his shoulder for ghosts, then begins writing his report. “His handwriting is minute. He gets a lot of words to the page.”

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then I recommend listening to:

36. The Liquidation Process (first half up to around the 21-minute mark)

Events are now moving very fast, so if you want to avoid spoilers, make sure you hit pause halfway through this final podcast. Mike Duncan’s series continues beyond April 1794, but this is the last episode to cover the events that take place in A Place of Greater Safety.

In the winter of 1793, two factions hurl abuse and accusations at one another at the Convention and the Clubs, and in their newspapers.

On one side are those pushing for the de-Christianization of France and the extension and expansion of the Reign of Terror. Max Robespierre calls these the “ultra-revolutionaries”. They are also known as the Exagérés or the Hébertists, after their most vocal leader, Jacques Hébert, and his newspaper alter ego, Le Père Duchesne.

The other side opposes de-Christianization and wants to slow or halt the Terror. Their opponents called them the Indulgents and Dantonists, after their leader, Georges Danton. Camille’s new publication, “Le Vieux Cordelier”, sets out their stall and competes directly with “Le Père Duchesne.”

Robespierre is instinctively sympathetic to the Indulgents, and initially supports them, denouncing de-Christianization and calling for a new committee to oversee the Revolutionary Tribunal. But the East India Company scandal and Camille Desmoulins’ forceful rhetoric convince him of a conspiracy behind the move towards moderation.

Jacques Hébert is wrongfooted by the popularity of “The Old Cordelier”. He goes on the offensive, stirring up the Paris sans-culottes for another coup to remove the moderates from the Convention. But there is little appetite among the sans-culottes for a new uprising: the Republic is winning the war, defeating provincial revolts, executing traitors and enforcing price controls.

The Committee of Public Safety moves against the Hébertists and the Paris Commune, executing Jacques Hébert. Meanwhile, the Committee of General Security (the “Police Committee” in APOGS) begins to round up those involved in the East India fraud scandal. However, the committees are divided about what to do with the biggest beast of them all, Georges-Jacques Danton.

Footnotes

1. Lucile’s journal

Another diary finished.

It is significant that a chapter named after Camille Desmoulins’ most important (and ineffectual) publication begins with his wife writing her unpublished and now lost journals. Lucile Desmoulins wrote poems, short stories and essays, none of them published in her lifetime. Sections of her diaries survived, including the months June 1792 through to February 1793. But of these last days we have nothing.

There will be soil and bones and grass, and they will read our diaries to find out what we were.

This thought recapitulates at the end of Bring Up the Bodies when Thomas Cromwell pictures the men who come after him turning him over to write on him. Crowmell’s words were destroyed the day he was arrested. And the Desmoulins will also burn their personal papers. The future will have to read the spaces in between.

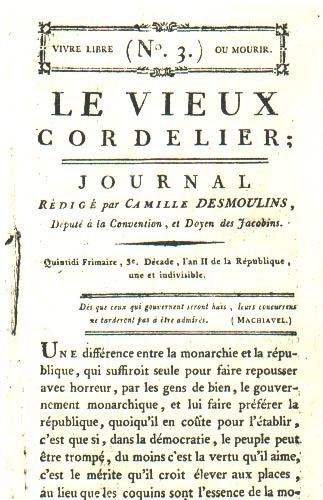

2. The Old Cordelier

‘In those days!’ Robespierre said. ‘The child talks as if it were in the reign of Louis XIV.’

Five years of revolution have aged me by fifty years. 700 pages of A Place of Greater Safety have chilled my blood. I am scared of my shadow. I wake at night.

Do you remember the good old days? When we moved onto the rue Cordeliers with our best mate next door, and history making itself in the streets? Take me back.

When Danton, Camille and Fabre graduated from running the Cordeliers Club to running the government, the radical Section was taken over by the sans-culottes. Now, their president is René Hébert, aka Père Duchesne. Listen to Max:

The new Cordeliers don’t represent anything, they don’t stand for anything – they just oppose and criticize what other people do, and try to destroy it. But the old Cordeliers – they knew what kind of revolution they wanted, and they took risks to get it. Those early days, they didn’t seem so heroic at the time, but they do looking back.’

Here is Camille writing in the first issue of “The Old Cordelier”:

I must write. I have to leave behind the slow pencil of the history of the Revolution I was tracing by the fire side in order to again take up the rapid and breathless pen of the journalist and follow, at full gallop, the revolutionary torrent.

Robespierre’s sanguinity won’t last long. The third issue compares the Terror with the oppressive reign of the Roman emperor Tiberius. In the fourth issue, Camille compares Robespierre to Julius Caesar and addresses his school friend directly.

“The Old Cordelier” wins him the approval of his father-in-law and (mild spoiler) his father – reversing his childhood dream to start something bloody that would upset his father.1 In this young republic, he, Camille Desmoulins, is the older generation. He is thirty-four.

It’s enough to get him thrown out of the Cordelier Club and denounced in the Jacobins – enough to get him killed.

Oh, and by the way, while we’re making Roman allusions: 1794 is the year when the word vandalism is coined to describe the de-Christianization policies of the Hébertists. The Vandals were a Germanic people whose 14-day sack of Rome in 455 established their reputation as the quintessential enemies of civilisation.

3. ‘Don’t mess about with my punctuation.’

'I thought you were heart and soul in this new paper, I thought you felt passionately?' 'I do feel passionately, and about punctuation too.'

This passage is a callback to Camille’s thoughts about an “artfully placed semicolon”, but it is also a message to Hilary Mantel’s own editors. The editor of Mantel’s first novel did mess about with her punctuation – and she did not work with them again. The editing of A Place of Greater Safety was also complicated by overzealous editing of tenses, partially corrected by Mantel, leaving some odd inconsistencies.

4. Vulnerable Robespierre

He felt guilty, about laughing at Max and saying he wanted to be God; he wasn’t God. God’s not so vulnerable.

Robespierre’s vulnerability makes him a compelling antagonist. Many readers have commented on his enigmatic personality. We readers, like Danton and Camille, find him impossible to fathom:

Presumably there was some layer of Robespierre, some deep stratum, where all the contradictions were resolved.

He hates violence, but oversees the Terror. He insists on putting the country first, but he also protects his school friend, Camille. He doesn’t want power, but cannot relinquish control. Criticism and failure sting him hard – and now I picture that scholarship student, reading his address to an absent King in the pouring rain, many years ago.

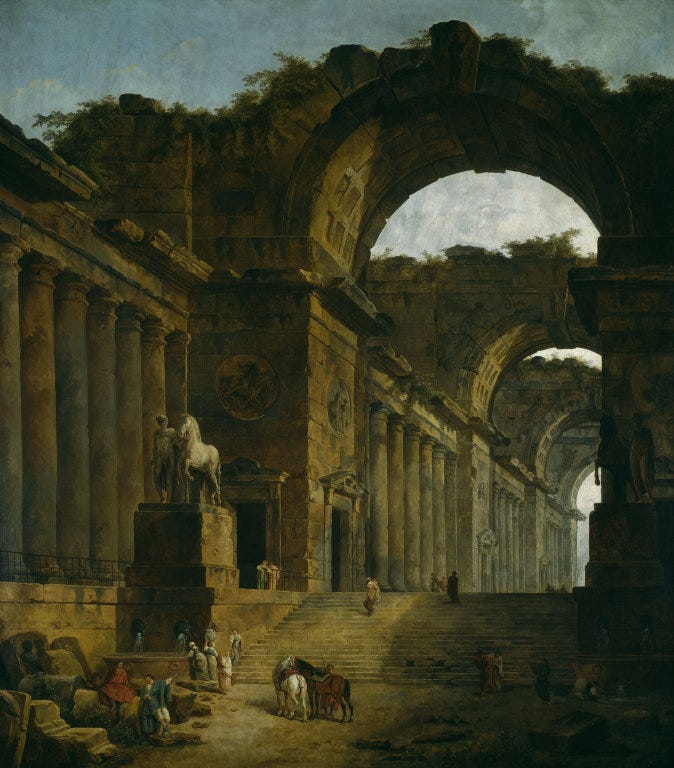

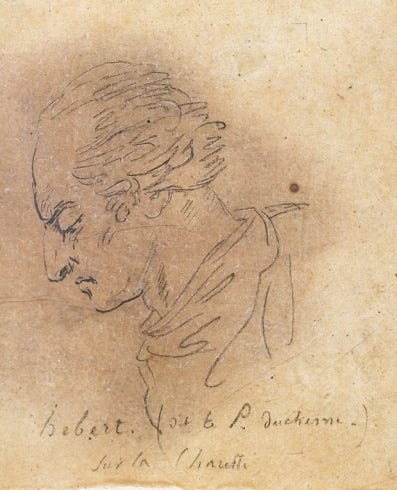

5. Get ready to be immortalised

Amazing, how resilient Fabre is. Camille, too. A small part of him feels like lead; the rest of him is ready for the fray, making the most of his capacity to drive people to a finger-twitching fury, or into a long, swooning, sentimental decline from sense. He feels light, very young. The artist Hubert Robert (whose speciality, unfortunately, is pictureseque ruins) is always on his heels these days; the artist Boze is contantly giving him hard looks, and occasionally walks over to him and with unfeeling artist hands pulls hs hair about. In his worse moods he thinks – get ready to be immortalized.

“Get ready to be immortalised” is my alternative title for this week’s reading. Here is the painting of Camille Desmoulins by Joseph Boze. Perhaps Camille would have preferred to be painted as one of Hubert Robert’s picturesque ruins:

6. Absolute power

This penultimate week gives us the climactic altercations between Max and Camille and Robespierre and Danton. In five years, little has changed in the relationship between Danton and the Incorruptible. And since they were school friends, Max has always wanted to protect Camille. But Camille is sick of being coddled, and he’s sick of Max’s abuse of virtue as a justification for murder. He gives us this belter:

‘What did we have the Revolution for? I thought it was so that we could speak out against oppression. I thought it was to free us from tyranny. But this is tyranny. Show me a worse one in the history of the world. People have killed for power and greed and delight in blood, but show me another dictatorship that kills with efficiency and delights in virtue and flourishes its abstractions over open graves. We say that everything we do it to preserve the Revolution, but the Revolution is no more than an animated corpse.’

On 4 December 1793, the National Convention passed the Law of 14 Frimaire:

The Executive Council, the ministers, generals and all consituted bodies, are placed under the supervision of the Committee of Public Safety.

This was designed to bring order to the Terror, reining in the excesses of provincial tribunals and bloodthirsty representatives on mission. However, it also suspended the democratic experiments of the Revolution, placing all elected bodies under the control of the Committee of Public Safety. As Camille says, “This is tyranny.”

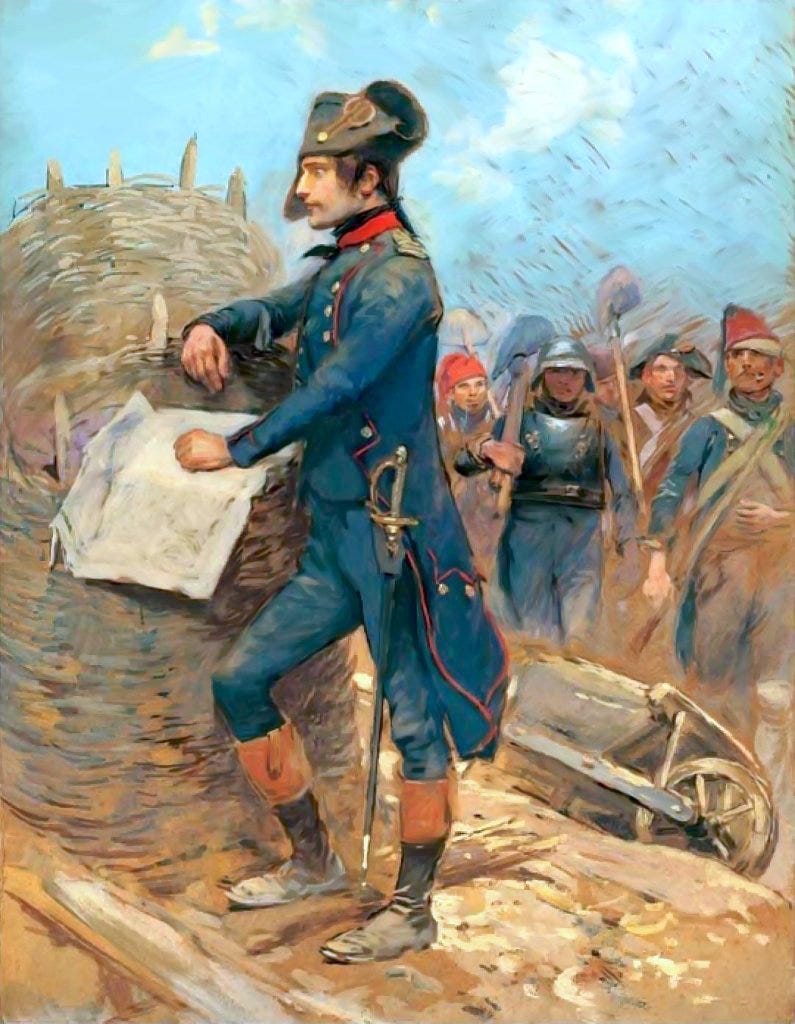

7. Toulon

‘I give Buonaparte three months before he gets his head cut off.’

Those of you who have read War and Peace, may remember Andrei Bolkonsky fantasising about “his Toulon”, where his strategic intervention would turbocharge his military career and save Russia.

Well, here’s Napoleon’s Toulon. The young artillery captain from Corsica devises the plan that successfully ends the siege of Toulon. Fabre is characteristically wrong about Buonaparte’s prospects. Napoleon will be made a general, fight in Italy and Egypt, before leading the coup of 18 Brumaire (9 November 1799) that will make him First Consul and later Emperor of the French.

But by then, we and Fabre will be long gone.

8. Danton vs Robespierre

‘I wonder if you’re real, I see you walk and talk, but where’s the life in you?’ 'I do live,' Robespierre looked down. He touched his fingertips together, like a nervous witness. 'I do live. In my fashion.'

We know that in March 1794, Robespierre and Danton met twice to reconcile their differences and avoid a bloody showdown.

Max may have begun the year in alliance with Camille and Danton against the “ultra” Hébertists. But since then, he has faced the double humiliation of Fabre’s deception and Camille’s criticism in the press. Both these men were Danton’s secretaries and his closest confidants.

Up until now, Robespierre has never doubted Danton’s republican principles, although he has disliked his methods and egotism. We see Max sitting on the fence, unwilling to wield the axe.

But Max’s belief that Danton destroyed Camille by encouraging him to criticise the Committee, and Danton’s refusal to abandon Fabre, are enough to convince him that there is a Dantonist conspiracy against the Revolution.

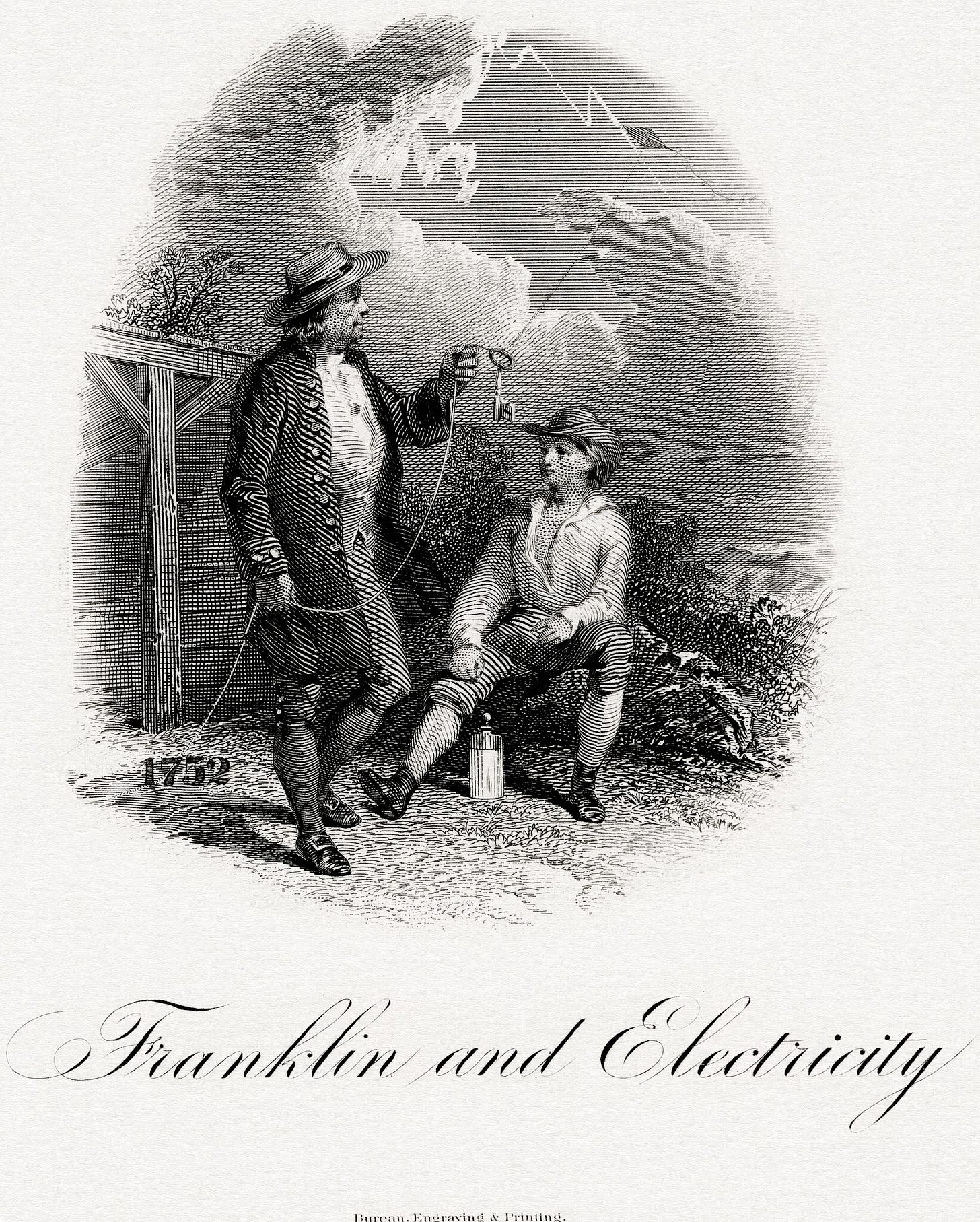

9. You are an electrical machine

So, said the body, you should not have treated me as your slave, abusing me with fasting and chastity and broken sleep. What will you do now? Tell your intellect to get you off the floor, tell your mind to keep you on your feet tomorrow.

When Robespierre falls ill, he feels in his pocket for a letter from Benjamin Franklin that told him, “You are an electrical machine.” I don’t know whether this letter existed, but we do know that Robespierre wrote to Franklin in 1783 after he won a court case in defence of the lightning conductor.

It is fitting that Max remembers this now, as his body and will seem to be failing. It is a reminder of a happier, simpler time. And now, he must become a machine, a conductor of the collective will, and do what is necessary to save himself and the revolution: kill his friend.

10. Apotheosis

‘For a little while I shall not be with you,’ Robespierre said. ‘Then, again, I will be with you.’

Robespierre (accidentally? deliberately?) quotes Christ’s words to his disciples before his death and resurrection. Our story has been full of confusing and contradictory allusions to Max as a Christ figure; allusions made by himself, his supporters and opponents.

It was thirty days since his withdrawal from public life. He felt as if all the years past he had been enclosed by a shell, penetrable to just a little light and sound; as if his illness had split it open, and the hand of God had plucked him out, pure and clean.

I am interested in how Mantel handles periods of illness as a storytelling device. Mantel endured long periods of illness when it was difficult or impossible to work. Thomas Cromwell falls ill twice in the Wolf Hall trilogy, and Anne Boleyn accuses him of falling ill only when it suits him. Robespierre’s illness resolves itself in a moment of clarity of purpose.

What caused these bouts of illness, and were they related to stress, nerves or depression? Mantel is always interested in the relationship between bodies, illness, individual perception and public actions.

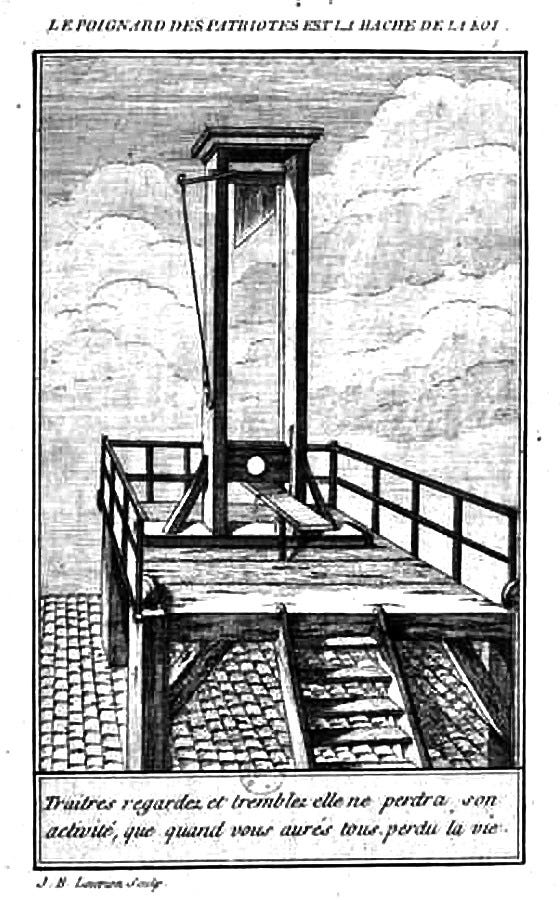

11. Hébert’s death

‘He should have been preceded by the furnaces; they could have turned it into a sort of carnival procession. He was not in one of his great cholers when he died. He was screaming.’

Hébert was arrested despite the reservations of some of the more hardline members of the Committee of Public Safety, like Collot d'Herbois, and Billaud-Varenne. The Revolutionary Tribunal tried him not so much as a political conspirator but as a common criminal. His execution attracted a large crowd and plenty of Schadenfreude as they watched the poetic justice of Hébert’s execution.

Camille says Hébert was screaming. Camille is not an impartial witness, and we shouldn’t trust his account. The Police reports mention only that Hébert looked sad and shaken, but various versions have embellished and exaggerated his behaviour to include repeated fainting and hysterical screaming. There is even a far-fetched claim that Sanson toyed with Hébert by letting the blade linger above his neck. Very unprofessional.

An eyewitness did say the Hébertists died “like cowards without balls” in stark contrast to the patriotic resolve of the Brissotins, singing “La Marseillaise.”

Nevertheless, his death marks a significant moment in the Revolution and the Terror. Hébert had taken over from Marat as the voice of the sans-culottes and the proponent of the most radical and violent policies of the revolution. After his execution, Saint-Just remarked that "the revolution is frozen." But the Terror is only getting started.

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will finish the book and read Part Five, Chapter XIII. Conditional Absolution

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

Interestingly, you could argue that Danton and Robespierre have replaced Camille’s father and father-in-law. Both behave like fathers to him, trying to protect him – and Max calls Camille a spoilt child at the Jacobin Club. Camille, the eternal enfant terrible, transfers his antipathy towards his parents onto his paternalistic/protective friends.

I've said it before - and I'll no doubt say it again - this all seems incredibly relevant today. I can't help thinking that the dynamics between Kennedy, Musk and Trump might be similar: best buds one day, plotting defenestration the next.

I'm surprised these people had so much time to have portraits painted - they do seem.rather busy with their intrigues. And were they capable of sitting still at all?

And Camilles none-too-private private life is an odd tangent. I mean, something else to fit into his extremely busy diary. Robespierre being slow on the uptake raised a smile with me.

But what's really catching my eye is the disconnect between the revolutionaries (who still seem to be having a fine old time) and the general population (which is starving). Brecht's 'food first, morals later' comes to mind.

We're almost at the end - in more ways than one - and I'm going to miss it.

I found it interesting that in this section we have a passage describing Max having a sleepless night. It’s a nice bookend to the sleepless night he has all the way back on pp103/104 (Fourth Estate paperback). At the time I thought the night he spent prior to sentencing someone to death for the first time was pretty horrific and nightmarish, but it’s nothing compared to the one he has now, on page 781. Then, he had at least attempted the consolation of prayer, now he cannot. He once bolted the door just once, now it’s three times. And when dawn came in the old times, he heard the hustle and bustle of warm-blooded human life, but now beyond his window he sees only shades, ghosts and slinking shadows. Life can always get worse. But Hilary always gives us some comic relief and I absolutely loved the constant references to the ‘new’ months that are never doing what they’re supposed to be doing. 😆 Thank you for guiding us nearly to the end now, Simon.