His face hardened. You can't stand in the street calling into question the last five years of your life, just because they've changed the street name; you can't let it alter the future. No, he thought – and he saw it clearly, for the first time – it's an illusion, about quitting, about going back to Arcis to farm. I've been lying to Louise: once in, never out.

last week | main page | reading schedule | cast of characters | further resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings.

This week, we are reading Part Five, Chapter X. The Marquis Calls.

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

The tyrants are dead, so why don’t we feel free? Hérault and Fabre dine with the Desmoulins. Hérault wants to get out of Paris – “a place for scavengers” – and Lucile and Camille exchange gallows humour that sickens Fabre. “It’s in the worst taste imaginable, and it’s not even funny.”

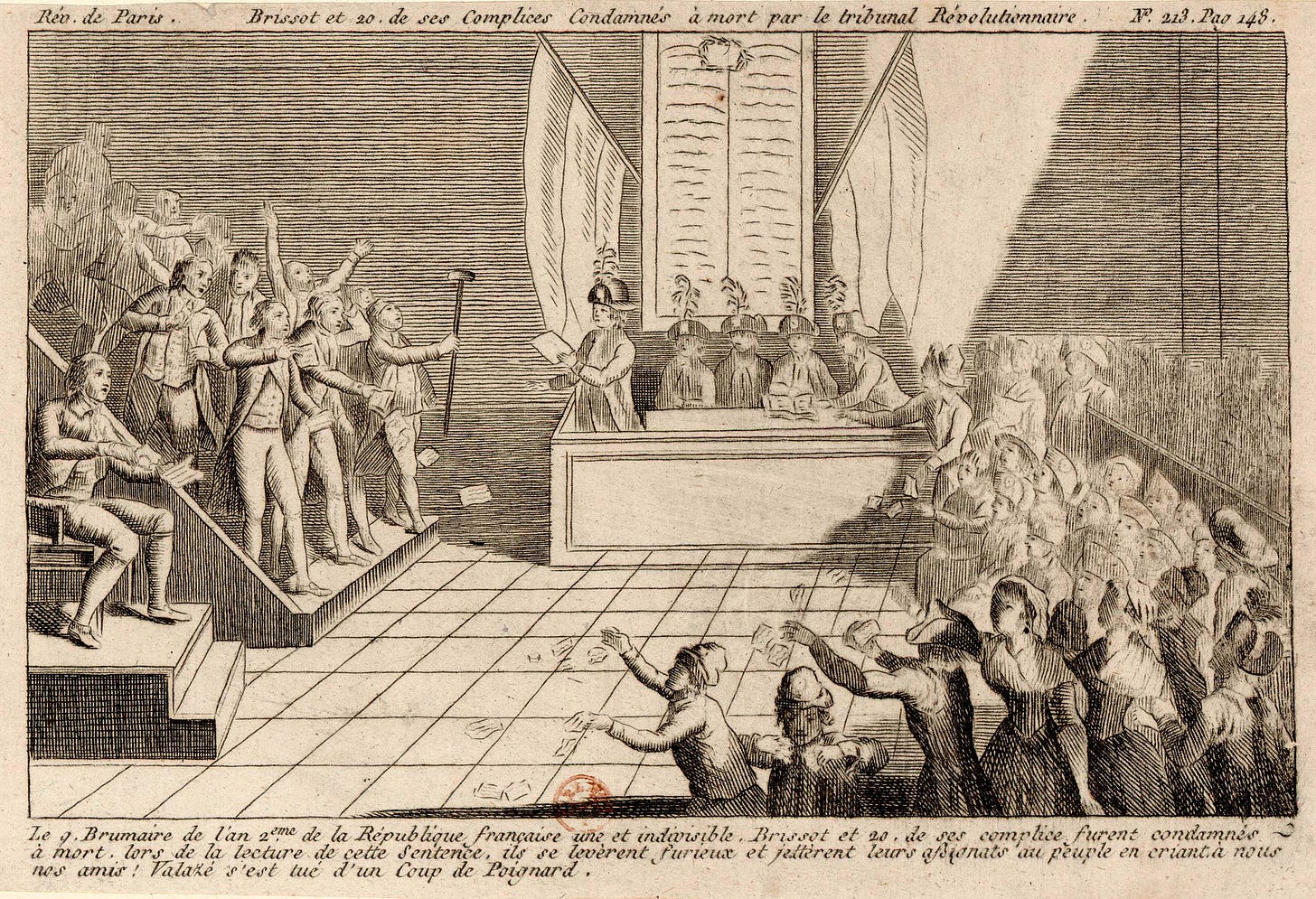

A few weeks later, Anne Théroigne visits Camille and asks him to denounce her as a Brissotin. He wants her dead for Louis Suleau, but he’ll not help her kill herself. At the Palais de Justice, he watches his cousin prosecute the Gironde. One of the accused, Valazé, commits suicide and Camille faints. “They were my friends,” he is heard to say. “And my writings have killed them.”

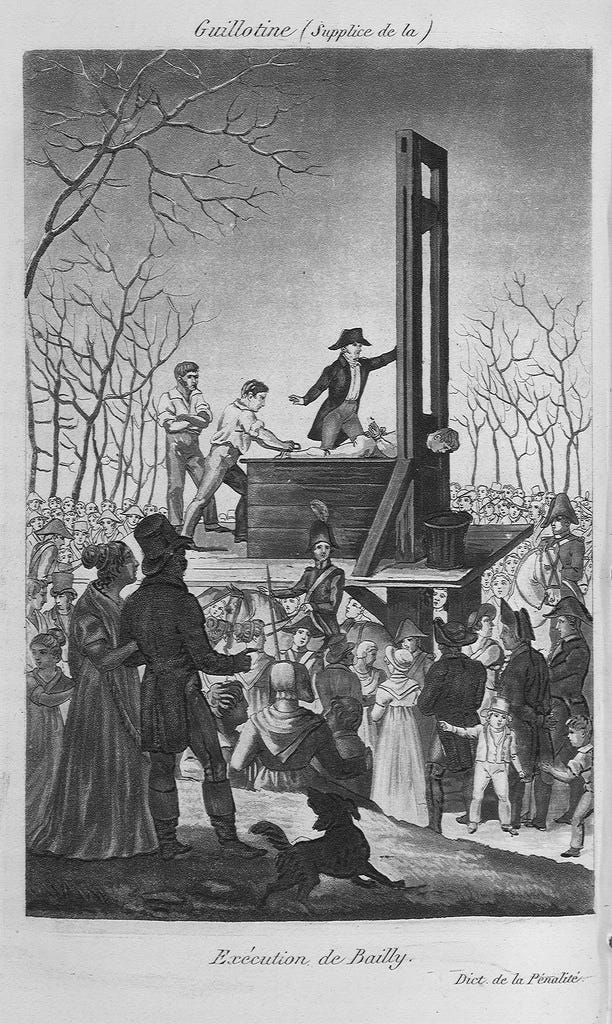

The twenty-one Brissotins are beheaded in thirty-six minutes, including Valazé’s corpse. Manon Roland follows soon after; her husband commits suicide outside Rouen. Vergniaud: “The Revolution, like Saturn, is devouring its own children.” Bailly and Philippe Égalité join the dead.

Max Robespierre is spitting blood about the atheist ‘Festival of Reason’ and writes to Danton to come back and help him destroy Hébert. The Citizen de Sade visits Camille and says the Terror must end. Camille, too, needs Danton back, and so does Fabre if Fabre wants to live.

Danton comes back to sort out the mess. He must get Fabre out of trouble. Lucile sounds desperate, Camille and Max have had a “little panic”, and he, Georges-Jacques Danton, has declared war on René Hébert. But first, he must do some thinking.

Danton abandons Hérault, but stands by Fabre. Fabre after all, has dirt on Danton, lest we forget. At the Jacobin Club, Robespierre defends Danton. In private, Danton and Camille mock Robespierre and Saint-Just. Fouquier-Tinville visits Lucile to warn her that her husband is being dangerously sentimental in public. “Concentrate on surviving yourself, my love, I do.”

At the Convention, Danton calls for restraint. His opponents accuse him of showing mercy. François Chabot is locked up for his involvement in the East India Company scandal. He resides in the Luxembourg.

We will be joining him soon.

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then I recommend listening to:

34. Saturn's Children (includes the trial of the Girondins)

34b. Philippe Égalité (optional but interesting)

In the autumn of 1793, the Terror continues in Paris and the provinces. Federalist defeats in Lyon and Marseille are followed by repression and mass executions. In August, republican forces besiege Toulon – an engagement that will transform the career of a young artillery officer called Napoleon Bonaparte.

The Revolutionary Tribunal sends the Girondins to the guillotine, followed by former mayor Bailly, Philippe Égalité and Manon Roland. By December, power has been centralised and consolidated in the Committee of Public Safety, effectively establishing Europe’s first experiment in totalitarianism.

Outside of the committee, two factions are emerging: atheistic ultra-revolutionaries coalescing around Jacques Hébert and voices of moderation led by Georges-Jacques Danton. Robespierre distrusts both sides, and it is unclear who will win.

She dragged herself from his grasp, ran into the bedroom and slammed the door. Her chest heaved, her heart rose and throbbed in her throat. With all the desperate passions in our heads and bodies, one day these walls will split, one day this house will fall down. There will be soil and bones and grass, and they will read our diaries to find out what we were.

Footnotes

1. The Trial of the Girondins

Occasionally, when some now-famous phrase feel on their ears, the accused would turn as one man and look at Camille. It was as if they had rehearsed it; no doubt they had.

We don’t need to get a Brissot in our bonnet about the portrayal of the Gironde in A Place of Greater Safety.

Jacques Pierre Brissot, Madame Roland, Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud, and their associates and allies may well form the moral backbone of the republican movement within the revolution – and they are perhaps its most tragic victims. Any history must recognise and evaluate this.

However, a novel serves different purposes: it reconstructs and reimagines a narrative from a carefully selected set of perspectives. Here, it is the psychodrama of three leading Jacobins. The focal point is their worldview and its fatal contradictions, and as Mantel explains in her Author’s Note, even Marat must be sidelined to tell a story of school friends turned sour.

Like Thomas More and Anne Boleyn in the Cromwell books, the Girondins suffer the fate of being relegated to the status of antagonists and minor characters. And so at their trial, what matters most is not their learned rebuttals to the false charges made against them, but the effect all this has on Camille:

Behind the Public Prosecutor, someone whispered, ‘Camille, what’s the matter?’

In fact, we see Brissot’s trial through the eyes of Camille’s cousin, Fouquier, the Public Prosecutor. This is on the heels of last week’s conversation between cousins, and is inevitably leading towards a day sometime soon when Fouquier will preside over Camille’s own trial.

As Camille later notes to de Sade, Brissot’s trial was complicated by the fact that the Girondins “were allowed to speak.” As accomplished lawyers, they were perfectly capable of representing and defending themselves against the absurd charges made against them. As martyrs to the revolution, they are remembered as sharing a last supper in prison the night before their execution. En route to the guillotine, they sang “La Marseillaise.”

The fall of the Girondins (World History Encyclopedia)

2. The last days of Manon Roland

‘I write these words to the sound of laughter in the next room …’

Manon had been arrested on 1 June 1793 when the Girondins were expelled from the Convention. She was imprisoned in the Prison de l’Abbaye for four weeks before being taken to the Saint-Pélagie Prison. She stayed there until the end of October, writing her memoirs and awaiting trial. She was moved to the Concièrgerie for the last eight days of her life.

According to posterity, her last words were: ‘O Liberté, que de crimes on commit en ton nom!’

3. Knitting the Revolution

People came to executions because they wanted to; but some of these old women, knitting for the war effort, you can see they’ve been paid to sit there, and they can’t wait to get away and drink up the proceeds; and the National Guardsmen, who have to attend, are sickened off after a few days of it.

A macabre passage imagines the Terror from the perspective of our overworked, exasperated public executioners, Charles-Henri Sanson and Sons. A family business that’s really gone to the dogs – guillotining the corpse of Dufriche de Valazé and men brought in “carts like calves” to the slaughterhouse.

There’s an apocryphal memoir of the Sansons, ghostwritten by Honoré de Balzac, edited with supplemental material by Henry-Clément Sanson, the last of seven generations of public executioners.

The Tricoteuse, or knitting women, were the female supporters of the Jacobins who attended the hearing of the Revolutionary Tribunal and allegedly brought their knitting to the scaffold to watch traitors die. They were made famous by Charles Dickens in A Tale of Two Cities, in the character of Madame Defarge.

Because our focus is on Paris, we do not see beyond Sanson’s workload. In Lyon, they have taken to mass executions with cannon. In Nantes, they are staging weekly mass drownings of clergy and other suspects. They are calling them “republican baptisms.”

4. The Festival of Reason

‘If there is no God,’ he said, ‘if there is no Supreme Being, what are the people to think who lived all their lives in hardship and want? Do these atheists think they can do away with poverty, do they think the Repbublic can be made into heaven on earth?’

This is another side of the widening rift between Robespierre and the “ultra-revolutionaries” who he thinks are discrediting the revolution with their overzealous iconoclasm. Chief among them is Jacques Hébert, who advocates for the continuation of the Terror, in contrast to the misgivings of Camille and Danton.

He wanted to ask Danton to come to Paris and help him crush Hébert. He wanted to say that he needed help, but would not be patronized: needed an ally, but would not be dominated.

The Cult of Reason was an attempt to establish an atheistic state-sponsored religion to replace Catholicism in the French Republic. Anti-clericalism provided support for the dechristianization of France, enabling the revolutionary cause to secure money and land. But targeting the clergy contributed to the revolution’s unpopularity beyond Paris and the provincial revolts that broke out in 1793.

Anacharsis Clootz declared that there was now “only one God, the people.” Cloots was a Prussian nobleman and an internationalist anarchist who advocated for a form of world government. In A Place of Greater Safety, Robespierre notes that Clootz is “a foreigner” – a hint at Max’s suspicious mind that links the atheists into a “foreign plot” designed to disrupt the revolution through acts of excess.

5. Saturn’s children

Remember that Vergniaud was the great orator of the National Convention, who impressed and irritated Danton. After the first failed attempt to expel the Girondins back in March, Vergniaud warned that, “The Revolution, like Saturn, is devouring its own children.”

This references the Greek myth about the titan Cronus (whom the Romans called Saturn), who ate one of his children out of fear of a prophecy that one of his children would overthrow him.

And in this chapter, the revolution really does begin to feast on its family.

Remember Jean-Sylvain Bailly? The astronomer stood at the centre of David’s “The Tennis Court Oath” as the Third Estate pledged to give France a new constitution in 1789. He’s beheaded on the Champs-de-Mars for his role in the “massacre” that took place there in 1791.

Remember our cousin, Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans? He who would be king and supported the freedom of speech at the Palais-Royal, which gave Camille his leg up into history? Philippe Égalité is now dead due to his son’s defection to the Austrians. In 1830, another French Revolution will remove Charles X and crown Phillipe’s son as a constitutional monarch.

6. Citizen Sade

‘I tell you, dear Citizen Camille – it’s not the deaths I can’t stand. It’s the judgements, the judgements in the courtroom.’

It’s kind of genius to have the Marquis de Sade drop in on Camille. Both men are famous for their violent prose. Both are about to lose their liberty to Robespierre’s reign of revolutionary despotism. And it feels incongruous to listen to the man who gave us sadism talking about stopping the Terror and ending the violence.

Sade tells Camille about the novel he wrote in the Bastille and which was lost when it fell: 120 Days of Sodom.

'Well, heavens,' Camille said, 'it's more than four years, haven't you had time to get it together again?' 'Not any old 120 days,' the Marquis said. 'It was a feat of imagination which in these attenuated times it is difficult to reproduce.'

Sade believes the book is gone forever. In fact, two days before the storming of the Bastille, a man called Arnoux de Saint-Maximin removed the manuscript. Around 1900, it reappeared in the hands of a German collector and was published by the Berlin psychiatrist and sexologist Iwan Bloch in 1904. Considered Sade’s masterpiece, 120 Days of Sodom was banned in France, the United Kingdom and the United States until the 1960s.

7. Endgame

I’m afraid I see no good coming of it. There was a point – it may have passed you by – when Danton and I abdicated from self-interest. When I say a point, I mean exactly that, a few seconds in which a decision was taken; I don’t say that afterwards we behaved differently, or better. When we planned how to win Valmy, we said we would never speak of it, not even to save our own lives.

Rather unexpectedly, Fabre breaks the fourth wall to remind us of his conspiracy with Danton to bribe the Duke of Brunswick with the stolen crown jewels. Fabre sees it as his insurance from being left out in the cold by Danton. Georges-Jacques wouldn’t dare betray Fabre because Fabre knows too much.

But then again, Fabre has already shown poor political judgment, and I wouldn’t put it past Danton to let Fabre take all the blame for everything.

We are entering the endgame. Danton has returned to help Camille stop the Terror and assist Robespierre in destroying Hébert and the “ultra-revolutionaries.” Thanks to Fabre, Chabot is being stitched up along with Hérault as the masterminds of a nefarious plot to defraud and undermine the revolution.

Marc-Guillaume Alexis Vadier chairs the Committee of General Security. They call him the “grand inquisitor.” He’s pretty sure Fabre, Danton and Camille are up to their necks in corruption and conspiracy.

‘We’ll clean up the rest of them, and leave that great stuffed turbot till the end.’

So Danton knows that time is running out. We stop the Terror before it stops us. If Max is mellowing, and Camille is sick of it, then perhaps it can be done. Who knows, perhaps we can all live and be friends afterwards?

Perhaps.

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Five, Chapter XI. The Old Cordeliers & Chapter XII. Ambivalence

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

Sometimes I think you must read A Place of Greater Safety at least three times to cast the spell correctly. First, to meet all the characters as strangers. Second, to meet them as friends, foes and familiars. Third, to meet them as ghosts. Don't believe me? All those crowded scenes in the earlier stages of the book take on a new frisson and a deeper chill once you know who is who and what will happen to each of them in the end.

I thought the section from the executioner was inspired. The way that Mantell breaks the tension of the narrative through this new perspective, while also allowing us to see the scale of the Terrpr was genius.

“Do the powers that be understand just how much blood comes out of a decapitated person?… it’s heavy work…”

It’s actually a fairly darkly humorous way of looking at the Terror, through the eyes of an overworked labourer. However, Mantell doesn’t allow us to sit in that space for long, as the horror of the situation is overwhelming. Lamenting the loss of esteem of the role of the executioner in a world where it is no longer special, he states “now they come in carts like calves, mouths sagging like calves and their eyes full, stunned into passivity by the speed which they have been herded from their judgement to their deaths, it is not an art any longer, it is more like working in a slaughterhouse”. And we’re worried about AI changing our jobs…